Gravitational wave astronomy is starting to do more than confirm Einstein’s equations. It is turning into a precision tool for mapping the invisible, with theorists now arguing that ripples in spacetime could expose how dark matter piles up around black holes. If that promise holds, the next generation of detectors will not just hear black holes collide, it will also let us probe the unseen substance that dominates the matter in the Universe.

Why black holes are the perfect laboratories for dark matter

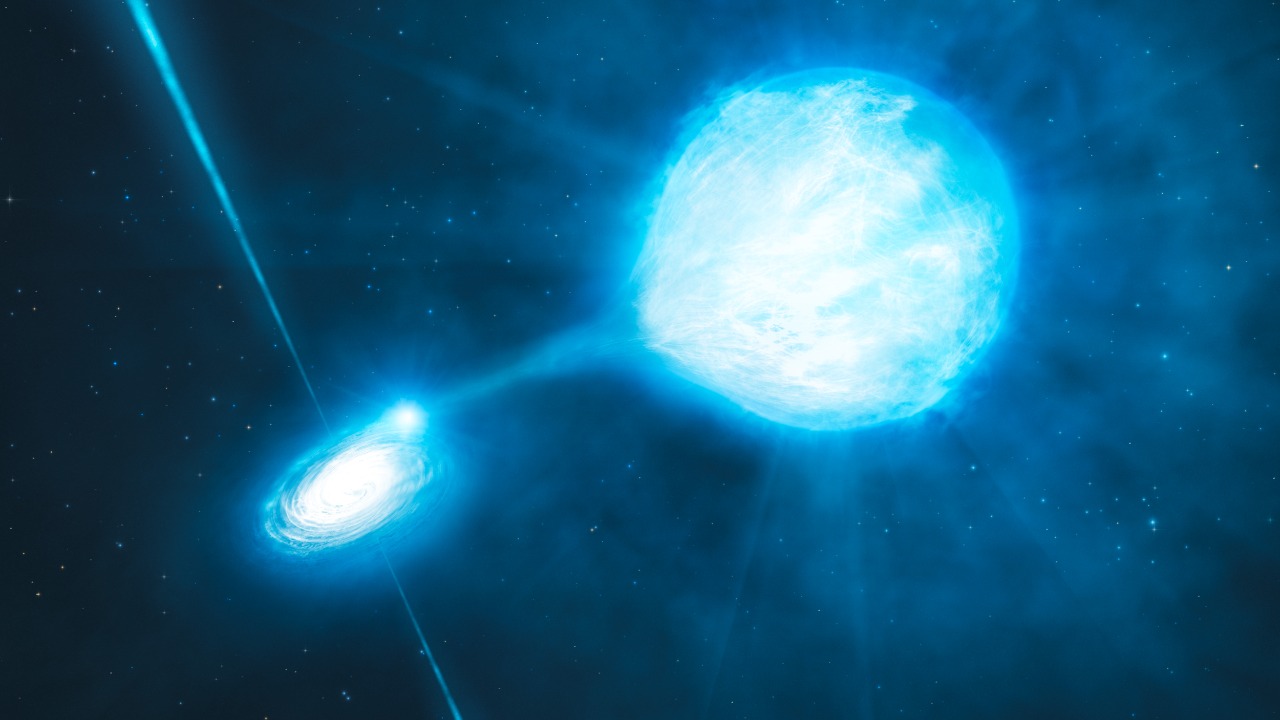

Black holes sit at the crossroads of gravity and particle physics, which makes them natural laboratories for testing ideas about dark matter. Their extreme gravity can reshape the distribution of any surrounding material, including the elusive particles that make up most of the matter in the cosmos, and that reshaping should leave a measurable imprint on how black holes move and merge. Theoretical work has shown that the formation and growth of black holes can strongly influence nearby dark matter, creating dense spikes or broader overdensities that differ from the smoother halos expected in standard cosmology, and those structures are exactly what gravitational wave measurements can hope to detect.

In a detailed analysis of how black holes and dark matter interact, one study argues that the way black holes grow, either by accreting gas or by merging with other compact objects, can sculpt pronounced matter overdensities around black holes. These overdensities change the gravitational potential in the immediate environment, subtly altering orbital speeds, inspiral timescales, and even the final recoil of merged black holes. If dark matter is not just a smooth background but instead forms these concentrated structures, then every black hole merger becomes a kind of seismograph, recording the invisible landscape in the pattern of waves it sends across the Universe.

From theory to signal: how dark matter distorts gravitational waves

To turn this conceptual link into a measurable effect, researchers have begun to calculate how specific dark matter distributions would modify the gravitational waveforms produced by orbiting and merging black holes. The basic idea is straightforward: if a black hole binary is embedded in a cloud of dark matter, the extra gravitational pull and any drag from that material will change the orbital energy and angular momentum over time. Those changes show up as tiny shifts in the frequency and phase of the emitted waves, which, with sufficiently sensitive detectors and accurate models, can be disentangled from the clean vacuum signals predicted by general relativity.

Recent work has focused on building waveform templates that include these environmental effects, so that data analysts can search for them in real observations. A new study framed as Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals and Long Gravitati examines how a small compact object spiraling into a massive black hole would respond to a surrounding dark matter spike. Because such systems orbit for thousands to millions of cycles before merging, even a slight additional force from dark matter can accumulate into a detectable phase shift. The challenge, and the opportunity, is that these subtle distortions are only visible if the theoretical predictions are precise enough to match the exquisite timing that future detectors will deliver.

Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals as dark matter detectors

Among all the gravitational wave sources on the table, Extreme Mass Ratio Inspirals, often shortened to EMRIs, stand out as particularly powerful probes of dark matter. In these systems, a stellar mass object, such as a neutron star or a small black hole, orbits a supermassive black hole in a tight, slowly decaying dance. Because the mass ratio is so large, the smaller object traces out the spacetime geometry of the larger one with high fidelity, and its orbit can be tracked over many years, which makes EMRIs ideal for spotting any deviations from the expected gravitational field.

The Dec reporting on Gravitational waves from black holes highlights how EMRIs could soon reveal the presence of dark matter near massive black holes. In that work, researchers at the Gravitation and Astroparticle Physics Amsterdam initiative, part of the Universiteit van Amsterdam, argue that the long duration and clean signal of EMRIs make them sensitive to even modest dark matter densities. By comparing observed inspiral rates and waveform phases with predictions that assume no surrounding material, they propose to infer whether a dense dark matter spike is present, and, if so, to estimate its profile. In effect, each EMRI becomes a test particle mapping the invisible matter around a supermassive black hole, turning gravitational wave observatories into dark matter detectors.

Decoding dark matter’s imprint on black hole mergers

While EMRIs offer a slow, detailed scan of a single black hole’s environment, more conventional black hole mergers also carry information about dark matter in their surroundings. As two black holes orbit each other and finally collide, they emit a burst of gravitational waves that can be detected with instruments on Earth, and the detailed shape of that burst depends on the masses, spins, and orbital configuration of the pair. If dark matter is present in significant amounts, it can influence how quickly the orbit shrinks and how the final merger unfolds, leaving a characteristic fingerprint in the waveform that careful analysis can extract.

A Dec feature on Decoding dark matter’s imprint on black hole gravitational waves explains how researchers are now building the first fully consistent models that include both the strong gravity of the black holes and the influence of a surrounding dark matter distribution. These models show that even for relatively short lived mergers, the presence of a dense dark matter halo can shift the timing and amplitude of the signal enough to be measurable with current or near future detectors. By fitting observed waveforms with these enriched templates, scientists hope to distinguish between different dark matter scenarios, such as cold collisionless particles versus more exotic self interacting candidates, based on how they affect the merger dynamics.

The University of Amsterdam’s push for precision waveforms

To make these ambitious measurements credible, the theoretical predictions must be pushed to a new level of precision, and that is where the University of Amsterdam has stepped in. A Dec announcement from the University of Amsterdam describes a study that provides the first fully self consistent calculation of how dark matter modifies black hole gravitational waves. Rather than treating the dark matter as a simple background, the team solves for the mutual interaction between the black holes and the surrounding material, capturing feedback effects that earlier, more approximate models could not handle. This level of detail is essential if analysts are to avoid mistaking dark matter signatures for other astrophysical effects, such as gas accretion or nearby stars.

In that Dec study, the researchers emphasize that their approach is designed to be directly usable in data analysis pipelines, not just as a theoretical exercise. By generating waveform families that span a range of dark matter densities and profiles, they create a library that can be matched against incoming signals from observatories. The goal is to turn each detection into a constraint on the properties of dark matter, potentially shedding light on its fundamental nature, such as whether it is made of weakly interacting massive particles or something more exotic. If these models hold up under the scrutiny of real data, they could transform gravitational wave catalogs into a new kind of dark matter survey, complementary to traditional searches that rely on light.

Supermassive black holes, pulsar timing, and the smallest scales of dark matter

Gravitational waves do not only come from stellar mass black holes, and recent work has drawn a surprising connection between supermassive black holes and the tiniest structures that dark matter might form. Researchers have proposed that the way supermassive black holes pair up and merge in galactic centers could be influenced by the presence of small scale dark matter clumps, linking some of the largest and smallest objects in the cosmos. This connection has practical consequences, because it affects the spectrum of low frequency gravitational waves that wash across the Milky Way and can be measured using pulsar timing arrays.

In a Jul report on Astrophysicists uncovering a supermassive black hole and dark matter link, the authors explain that a prediction of their proposal is that the spectrum of gravitational waves observed by pulsar timing arrays should be sensitive to the properties of dark matter on very small scales. If dark matter forms compact clumps or has interactions that change how it clusters, those features would alter how efficiently supermassive black holes can find each other and merge, which in turn would reshape the background of low frequency waves. The same Jul work notes that this idea could help address the long standing “final parsec problem” in astronomy, which asks how supermassive black holes close the last bit of distance to merge, by invoking the gravitational influence of dark matter structures that assist in draining orbital energy.

A new link between supermassive black holes and dark matter halos

Independent of pulsar timing, other researchers have been exploring how the large scale relationship between supermassive black holes and their host galaxies might encode information about dark matter. Observations show that the masses of central black holes correlate with properties of the surrounding galaxy, such as the velocity dispersion of stars, and these correlations are often interpreted as evidence of coevolution. If dark matter plays a key role in shaping galactic potentials, then it should also influence how supermassive black holes grow and how often they merge, which again feeds back into the gravitational wave signals we can observe.

A Jul analysis reports that Researchers have found a link between some of the largest and smallest objects in the Universe, specifically supermassive black holes and dark matter structures, that could help solve the final parsec problem. By modeling how dark matter halos and subhalos interact with binary black holes in galactic centers, they show that these invisible components can provide the necessary gravitational torques to bring black holes together. This mechanism not only offers a path to more frequent mergers, boosting the expected gravitational wave background, it also suggests that careful measurements of that background could reveal the underlying dark matter distribution that made those mergers possible in the first place.

Early hints that gravitational waves can already test dark matter

Although much of the current excitement focuses on future detectors and more precise models, the basic idea that gravitational waves can probe dark matter is not entirely new. Years before the latest theoretical advances, some researchers had already pointed out that black holes and dark matter are connected in ways that gravitational wave observatories could exploit. The core insight is that measuring the waves emitted by merging black holes can, in principle, reveal whether those black holes formed and evolved in environments rich in dark matter, or in regions where it is relatively scarce.

One early study argued that Black holes and dark matter are connected, and that measuring gravitational waves emitted by merging black holes can thus provide clues about the nature of dark matter. The authors emphasized that the rate and characteristics of detected mergers, such as the typical masses and spins of the black holes involved, depend on how those objects formed within dark matter halos. If dark matter enhances the formation of certain types of binaries or affects how they migrate within galaxies, then the statistical properties of gravitational wave catalogs become a powerful, indirect probe of the dark sector. Those early ideas are now being sharpened by the more detailed waveform modeling and environmental calculations emerging from groups around the world.

What the next decade of detectors could reveal

Looking ahead, the real test of these ideas will come from the next generation of gravitational wave observatories, which promise both higher sensitivity and access to new frequency bands. Space based detectors will be particularly important for EMRIs and supermassive black hole mergers, where dark matter effects are expected to be strongest, while improved ground based instruments will collect larger samples of stellar mass black hole mergers in a variety of environments. Together, these facilities will provide the raw data needed to turn theoretical predictions about dark matter induced waveform distortions into concrete measurements and constraints.

At the same time, coordinated efforts are underway to refine the theoretical tools that will interpret those signals. A Dec release on Decoding dark matter’s imprint on black hole gravitational waves underscores how teams are building end to end frameworks that connect particle physics models of dark matter to astrophysical predictions and finally to observable waveforms. By embedding dark matter effects directly into the templates used in data analysis, they aim to ensure that any deviations from standard predictions are not dismissed as noise or modeling error. If successful, this strategy could turn every new gravitational wave detection into a small but meaningful experiment on the nature of dark matter, gradually narrowing the range of viable theories and perhaps, eventually, pointing to a specific particle or interaction that explains the invisible mass shaping the cosmos.

More from MorningOverview