Artificial intelligence has just helped virologists pull off something that used to take years of trial and error: crippling a virus by changing a single molecular contact point. Instead of screening thousands of drug candidates, researchers used machine learning to zero in on one amino acid interaction that acts like a hidden power switch for infection. By flipping that switch, they stopped the virus from ever getting inside cells.

The result is more than a clever lab trick. It is an early, concrete glimpse of how AI could turn antiviral design into a precise engineering problem, where models map out viral weak spots and scientists move straight to targeted fixes. I see this as a template for how future therapies might be built, not by chance, but by computation-guided design.

The tiny viral weak point that changed everything

The breakthrough started with a deceptively simple question: if a virus depends on a fusion protein to punch its way into cells, is there a single point on that protein that everything else quietly depends on. Using AI, researchers found exactly that, a hidden molecular interaction that functions like a hinge in the fusion machinery. When they altered one key amino acid in that hinge, the entire fusion protein lost its ability to drive entry, and infection stopped before it began.

Instead of broadly damaging the viral shell, the team focused on a specific contact that viruses depend on to enter cells, a strategy that came directly from model predictions rather than blind screening. Once the key amino acid was identified, changing it disrupted the coordinated movement of the entire fusion protein, a result that was later confirmed in structural and functional assays described in detail in AI-guided fusion studies.

How AI spotted a “hidden” interaction humans kept missing

What made this work different from classic virology is that the crucial interaction was not obvious from standard structural diagrams. The weak point sat buried in a dense network of amino acids, where small shifts ripple through the protein in ways that are hard for humans to intuit. By training on large datasets of protein behavior, the AI system learned to flag which single-site changes would have outsized effects on the fusion process, even when those sites looked unremarkable at first glance.

In practice, that meant the model could simulate how tiny tweaks would alter the choreography of the fusion protein long before anyone touched a pipette. The researchers then tested a short list of high-impact candidates in the lab, quickly confirming that one predicted change shut down the fusion step that viruses depend on to enter cells, a result that aligns with the mechanistic description in AI-focused virology work.

From infection to prevention: blocking the virus at the door

Most antiviral drugs that I have covered over the years share a common limitation, they act only after the virus has already slipped inside the cell and started to replicate. In this case, the strategy flipped that script. By disabling the fusion protein’s critical interaction, the researchers effectively locked the door before the virus could cross the threshold, preventing infection from starting at all rather than trying to clean up the damage later.

That shift in timing is not just a scientific curiosity, it has practical implications for how we think about outbreaks and treatment windows. If you can block entry, you reduce the viral load that ever takes hold in the body, which could make therapies more forgiving when people start them late and less likely to drive resistance. Reporting on this work has emphasized that Most antiviral drugs target viruses after they have already slipped into cells, which is precisely the gap this AI-guided approach is designed to close.

What “one tiny change” actually looks like in molecular terms

When people hear that one tiny change stopped a virus, it can sound like marketing shorthand, but at the molecular level it is literally true. The AI model highlighted a single amino acid whose side chain helped stabilize a key contact in the fusion protein. Swapping that residue for a different one changed the local chemistry enough to destabilize the interaction, which in turn prevented the protein from undergoing the shape shift it needs to fuse viral and cellular membranes.

In structural biology language, the mutation disrupted a tiny molecular interaction that viruses rely on as a key step in their life cycle. The team did not have to redesign the entire protein or bombard it with random mutations. Instead, they used AI to identify one precise molecular interaction that viruses depend on to enter cells, then validated that prediction experimentally, a process summarized in accounts of how Using AI allowed researchers to pinpoint that single contact.

Why this matters for future pandemics

From my perspective, the most important part of this story is not the specific virus, but the playbook it suggests for the next unknown pathogen. If AI can map out the fusion machinery of one virus and find a hidden hinge, the same approach could be applied to other enveloped viruses that use similar entry tricks. Instead of waiting months to understand how a new threat gets into cells, models could rapidly propose a shortlist of vulnerable interactions that drug designers or vaccine developers can target.

That is especially relevant in a world where outbreaks move faster than traditional lab pipelines. AI-guided analysis can compress the early discovery phase, turning raw sequence data into actionable hypotheses about where to intervene. Work on models like the ProRNA3D-single system, which generates new data about RNA-protein interactions and can be applied to any use case, shows how groundbreaking AI is already being built to speed lifesaving therapies by exploring molecular spaces that are too complex for manual reasoning alone.

Inside the AI toolbox: from protein structures to viral behavior

Under the hood, the models used in this kind of work are essentially pattern recognizers trained on huge libraries of protein structures and sequences. They learn which amino acid combinations tend to stabilize certain shapes, which contacts are fragile, and how small changes propagate through a protein’s 3D form. When applied to a viral fusion protein, that knowledge lets the AI simulate how a single mutation might ripple through the structure and either leave function intact or knock it out.

In the virus study, the AI did more than just predict a static structure. It helped researchers understand how the fusion protein moves as it transitions from a pre-fusion to a post-fusion state, and which interactions act as control points in that motion. That dynamic view is crucial, because the weak point they exploited was not simply a loose bond, it was a contact that controlled a larger conformational change. Related work on viral entry has described how Researchers discovered a hidden molecular interaction that functioned as exactly that kind of control point, reinforcing the idea that AI is particularly good at surfacing these subtle, dynamic dependencies.

From lab bench to real-world therapies

Turning a single amino acid tweak into a real-world therapy is not automatic, and I think it is important to be clear about that. What the AI-guided mutation gives scientists is a validated target, a specific interaction that, if disrupted, stops the virus from entering cells. Drug developers can now design small molecules, peptides, or antibodies that mimic the effect of that mutation, binding to the fusion protein in a way that destabilizes the same contact without needing to alter the viral genome directly.

That is a very different starting point from traditional drug discovery, which often begins with broad chemical libraries and only later tries to understand what the hits are doing. Here, the mechanism is known from day one, and the screening can be focused on compounds that interfere with a clearly defined interaction. As more AI systems like ProRNA3D-single and the models used in this viral work mature, I expect to see a growing pipeline of therapies that begin with a computational map of weak points and move quickly into targeted design, rather than relying on serendipity or brute-force searches.

The bigger picture: AI as a partner, not a replacement, in virology

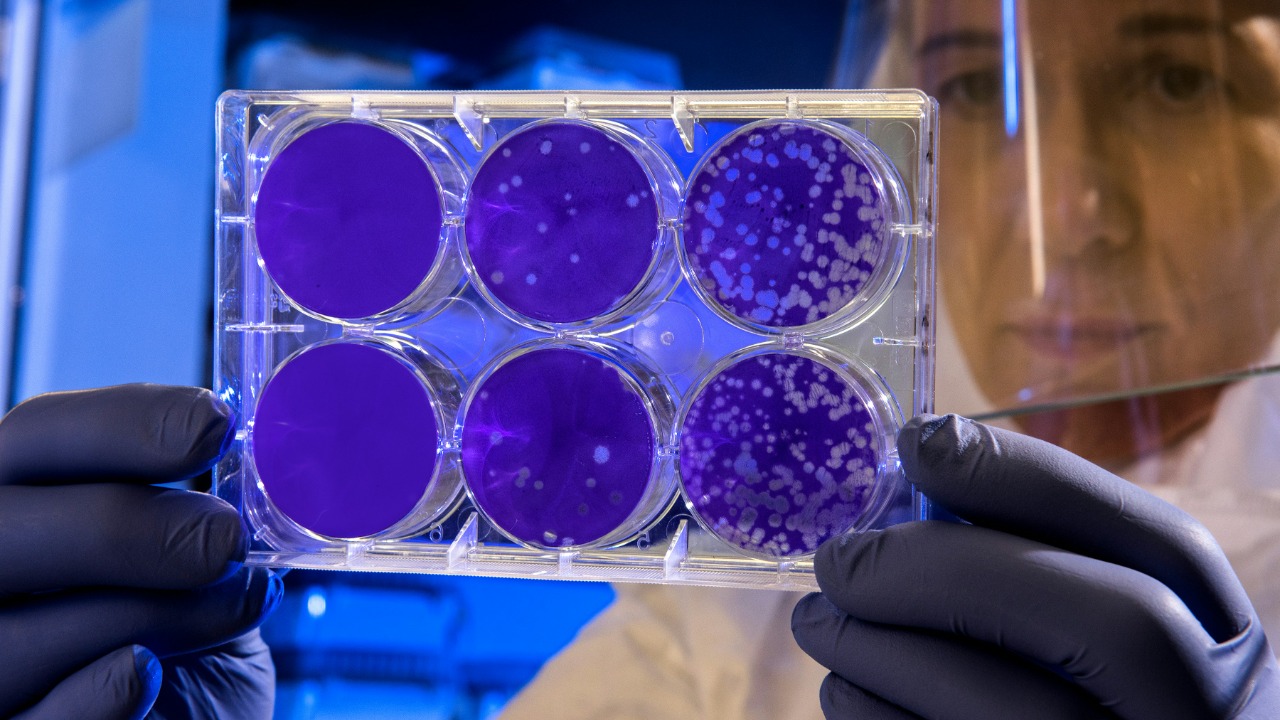

For all the excitement around this result, I see it less as proof that AI can replace virologists and more as evidence that it can act as a powerful partner. The models did not run the experiments, interpret the cell cultures, or validate the structural changes. Human researchers still had to decide which predictions were worth testing, design the mutations, and interpret unexpected results. What AI did was compress years of guesswork into a shortlist of high-value hypotheses, effectively amplifying the insight of the people in the lab.

That partnership model is already visible across molecular biology, from RNA-protein interaction tools like ProRNA3D-single to the fusion-focused systems that identified the viral weak point. The common thread is that AI excels at sifting through enormous combinatorial spaces, whether that is the countless ways an RNA strand can fold or the many possible amino acid substitutions in a viral protein. By letting algorithms handle that search, scientists can focus on the creative and interpretive work that still requires human judgment, which is exactly what happened when AI Helped Scientists Stop a virus with one carefully chosen change.

More from MorningOverview