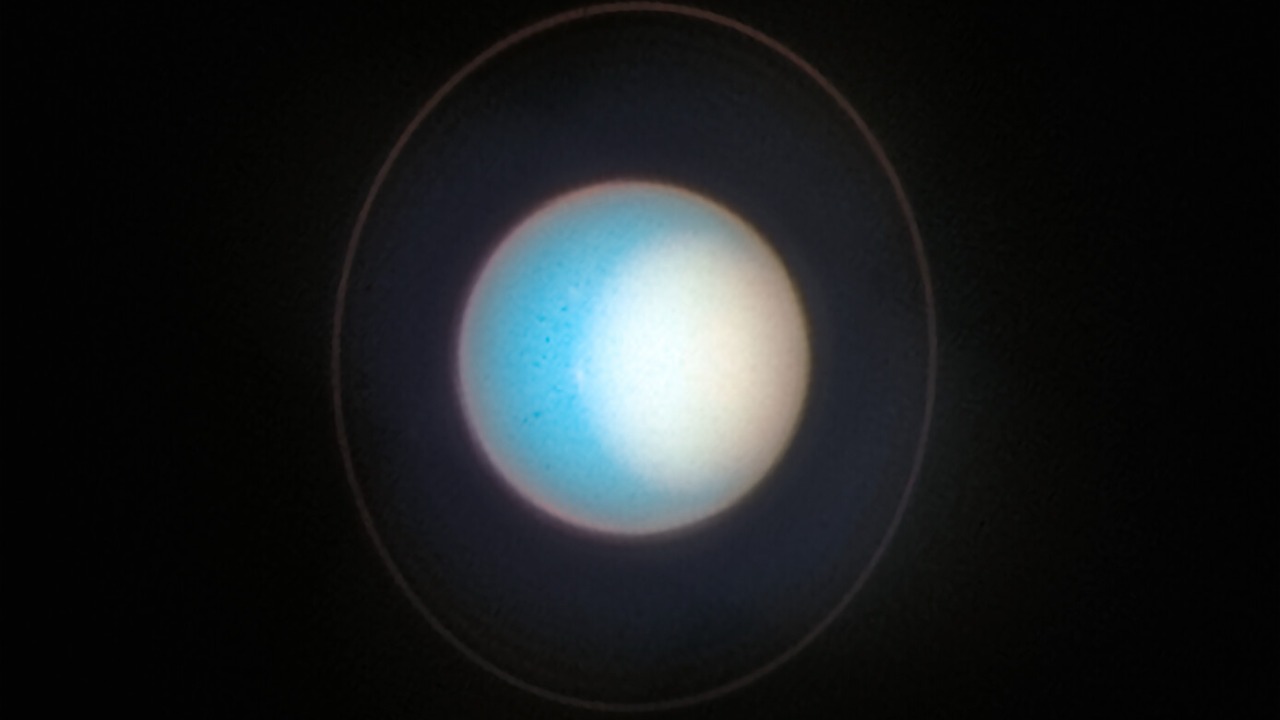

Far from the Sun, Uranus has long looked like a quiet, teal marble in the dark. Yet a reexamination of decades old spacecraft readings now points to a violent episode in its past, when a blast of solar wind appears to have stripped and then supercharged the planet’s magnetic environment. That ancient space weather event is emerging as the key to understanding why Uranus carries some of the most extreme radiation belts in the outer solar system.

By tying those belts to a rare compression of the planet’s magnetosphere, researchers are rewriting what I thought I knew about Uranus, its potential habitability, and even how we plan the next flagship mission there. The story begins with a single flyby, a strange magnetic field, and a dataset that scientists refused to let gather dust.

Voyager 2’s brief visit and a decades long puzzle

When NASA’s Voyager 2 swept past Uranus in 1986, it delivered the only close up measurements humanity has ever made of this distant world. The spacecraft’s instruments mapped a lopsided magnetic field, sampled charged particles, and sketched out the planet’s radiation belts, giving scientists a first look at a system that turned out to be far stranger than the more symmetric environments at Jupiter and Saturn, as later summaries of the NASA Voyager Uranus encounter make clear.

Those early measurements suggested that Uranus’s belts were unexpectedly intense and that its magnetic field was unusually tilted and offset from the planet’s center. For nearly forty years, researchers treated that snapshot as representative of normal conditions, building models of the planet’s interior and atmosphere around it, even as the original Voyager 2 data sat in archives waiting for more sophisticated analysis.

A magnetosphere caught in a rare, squashed state

The turning point came when a team went back to the original dataset and realized that Uranus’s magnetic bubble had been in an “anomalous, compressed” configuration during the flyby. In a detailed reanalysis, the authors explicitly state, “Here we revisit the Voyager dataset to show that Voyager 2 observed Uranus’s magnetosphere in an anomalous, compressed state,” arguing that the planet’s magnetic shield had been squeezed and partially emptied of plasma at the time of the encounter, as described in their Nov Here Voyager Uranus analysis.

The same study’s abstract emphasizes that The Voyager 2 flyby revealed an unusually oblique and off centered magnetic field, and that this single pass happened while the magnetosphere was temporarily stripped of much of its plasma, a combination that made the system look more extreme than it typically is. In the authors’ words, captured in the Nov Abstract The Voyager Uranus description, the spacecraft essentially caught the planet in the middle of a magnetic storm rather than in a calm, average state.

A powerful solar wind blast as the trigger

To explain that compressed configuration, researchers traced the disturbance back to the Sun. By comparing the timing of the flyby with records of solar activity, they concluded that a surge of plasma from the Sun had slammed into Uranus’s magnetic field, squashing the magnetosphere to a fraction of its usual size and driving material out of the system. One summary of the work notes that when plasma from the Sun pounded and compressed the magnetosphere, it likely drove plasma out of the system, a scenario laid out in detail in the Nov When Sun discussion of the event.

Independent coverage of the same research describes how unusual solar activity just before the encounter squashed the planet’s magnetic bubble down to about 20 percent of its original size, a configuration that is thought to occur only rarely. One technical overview puts it bluntly, noting that, indeed, just before the flyby, the solar wind “squashed” Uranus’s magnetosphere and that it is not generally like that, a point underscored in the Jan Indeed account of the compression.

Reframing Uranus’s extreme radiation belts

For years, the intensity of Uranus’s radiation belts puzzled scientists, because the measured particle fluxes seemed too high for a planet so far from the Sun. A recent study from Southwest Research Institute argues that the key is timing, indicating that the Uranian system may have experienced a space weather event during the Voyager visit that altered the belts’ structure and energy distribution, as summarized in the Dec Uranian Voyager description.

That work suggests that the belts we saw were not a steady state feature but the aftermath of a powerful solar wind impact that had reconfigured the planet’s trapped particle environment. By tying the observed intensities to a transient event, the researchers argue that Uranus’s radiation belts may not be as persistently extreme as once thought, a conclusion that aligns with the broader picture of a magnetosphere temporarily stripped of plasma and then refilled in complex ways, as described in the Dec Edited By Joshua Shavit Far Sun Uranus coverage of the solar wind clue.

Mining old data with new analysis tools

The reappraisal of Uranus’s radiation environment did not come from new spacecraft, but from new ways of looking at old measurements. Researchers used modern analysis techniques to revisit the Voyager 2 readings, comparing them with models of how the magnetosphere should behave under normal space weather conditions and under the influence of a strong solar wind shock. One account notes that the new study compares Voyager data with expectations for the planet’s magnetic system under normal space weather conditions, highlighting how far the flyby state deviated from the norm, as described in the Dec Voyager Image Getty Space summary.

Another overview emphasizes that researchers revisited the measurements almost four decades later, using improved models and computational tools to tease out signatures of the solar wind event that had been overlooked. That same report notes that Space.com described how new analysis of Voyager 2 data suggests the spacecraft flew through Uranus’s magnetosphere during an extreme compression, a point captured in the Dec Voyager Image Getty Space description of the research methods.

How rare was Voyager 2’s “chance encounter”?

One of the most striking claims to emerge from the reanalysis is just how unusual the flyby conditions were. Scientists now estimate that the configuration Voyager 2 sampled occurs only about 4 percent of the time, meaning the spacecraft effectively caught Uranus during a rare magnetic contortion rather than in a typical state. A detailed write up notes that “the spacecraft saw Uranus in conditions that only occur about 4% of the time,” and that the magnetic fields around planets like Uranus can trap charged particles into pockets called radiation belts, as highlighted in the Nov Uranus Magnetic coverage.

Other commentators have gone further, describing the encounter as a freak event and a chance alignment of timing and solar activity. One analysis states that They have found that Voyager 2’s flyby was a freak event, with the spacecraft passing Uranus during an “extreme” configuration of the planet’s magnetic field, a characterization that appears in the Nov They Voyager Uranus discussion of the chance encounter.

Extreme radiation levels and the lingering mystery

Even with the solar wind explanation, Uranus’s radiation belts remain formidable. Reports on the Voyager 2 measurements describe “extreme radiation levels” at the planet, with unusually powerful high frequency waves detected in the environment around the planet. One account notes that extreme radiation levels were detected at Uranus and that the mystery continues, emphasizing that the planet’s strangely intense radiation environment is linked to unusually powerful high frequency waves, as detailed in the Dec Extreme Uranus report.

Southwest Research Institute scientists have tried to quantify just how intense those belts are, pointing out that the energy levels Voyager 2 observed were surprisingly high for such a distant world. A recent summary notes that SwRI may have solved a mystery surrounding Uranus’ radiation belts by explaining how a space weather event could have produced the energy levels Voyager 2 observed, a conclusion captured in the Dec Uranus Southwest Research Institute description of their work.

What the belts reveal about habitability and hidden oceans

The new picture of Uranus’s radiation belts has implications that reach far beyond magnetospheric physics. Early interpretations of the Voyager data suggested that the planet’s moons and potential subsurface oceans would be bathed in such intense radiation that complex chemistry or life would be unlikely. By reanalyzing the readings in light of the recorded outburst of solar wind, the researchers behind the new study found that the belts may not always be as harsh as the 1986 snapshot implied, a point emphasized in the Nov account of the revised view.

At the same time, some interpretations of the original data argued that Uranus’s radiation belts, as seen by Voyager 2, suggested the planet therefore likely lacked hidden oceans, because the observed particle environment did not match expectations for a system with large internal water reservoirs. That line of reasoning, summarized in the Nov Uranus Magnetic discussion, is now being revisited as scientists weigh how much of the environment Voyager saw was shaped by a one off solar wind blast rather than by the planet’s long term internal structure.

Why Uranus is back on the mission priority list

All of this is happening as planetary scientists push hard for a dedicated Uranus orbiter and probe. The realization that Voyager 2 may have captured the planet in a rare, storm driven state has strengthened the case that a single flyby is not enough to characterize such a complex system. One institutional summary notes that analysis of old space mission data has helped solve several Uranus mysteries, but also stresses that the findings are helping define science goals for a future NASA mission, as described in the Mining old data overview.

Researchers at Southwest Research Institute have also highlighted how limited our direct measurements still are, pointing out that, to date, the Voyager 2 probe has provided the only direct measurements of the radiation environment at Uranus and that no spacecraft has returned since. A recent summary quotes their assessment that this lack of follow up has left key questions unanswered for decades, a concern laid out in the Dec Voyager Uranus description of the measurement challenge.

How the new picture reshapes four decades of assumptions

Stepping back, the emerging consensus is that we have been wrong, or at least incomplete, in our understanding of Uranus for nearly forty years. Commentators have argued that the chance timing of the flyby tricked scientists into believing Uranus could not host life or hidden oceans, because the extreme magnetic and radiation conditions looked permanent rather than transient. One widely cited analysis states that They (astronomers) have found that Voyager 2’s flyby was a freak event and that the spacecraft did not provide an accurate snapshot of the planet’s magnetic field, a point captured in the They Voyager Uranus description.

At the same time, the more technical literature has framed the shift as a refinement rather than a wholesale reversal, emphasizing that the oblique, off centered field and the existence of strong radiation belts are real, but that their exact configuration during the flyby was shaped by a rare solar wind event. The detailed Nov NASA Voyager Uranus summary of the reanalysis underscores that by treating the Voyager 2 encounter as a single, storm biased data point, scientists can now build more realistic models of the planet’s magnetic system and its long term interaction with the solar wind.

More from MorningOverview