Solar power has long been constrained by a supposedly unbreakable ceiling on how much sunlight a panel can turn into electricity. That barrier is now cracking as a new class of solar materials pushes conversion rates into territory that once looked “theoretical” on lab whiteboards. The result is a race to redesign panels, power plants, and even city rooftops around devices that can do far more with the same patch of sunlit glass.

At the center of this shift is a family of crystalline compounds that can be layered on top of conventional silicon to capture more of the solar spectrum. By combining these materials with clever device architectures, manufacturers are reporting efficiencies that leap beyond the long accepted limit for single-junction silicon, hinting at a future where solar farms shrink, costs fall, and clean power becomes even harder for fossil fuels to compete with.

From “theoretical limit” to record-breaking reality

For decades, engineers treated the Shockley–Queisser limit as a kind of law of nature for standard solar cells. In a single layer of silicon, much of the incoming sunlight is either too low in energy to be absorbed or so energetic that the excess is lost as heat, a process described in detail in work on solar-cell efficiency. That physics caps a traditional silicon panel at roughly thirty percent efficiency, and in practice most commercial modules have sat well below that, leaving a large gap between what hits the glass and what reaches the grid.

The new generation of devices attacks that gap head on by stacking multiple light-absorbing layers with different bandgaps so that each slice of the spectrum is used more intelligently. These so-called tandem designs are no longer just academic curiosities. Earlier this year, giant Chinese solar panel manufacturer Longi reported a power conversion efficiency of 34 for one of its advanced cells, a figure that would have looked implausible for a silicon-only device. That headline number signals that the field has entered a new phase where “theoretical” limits are being redefined by practical engineering.

Perovskite steps into the spotlight

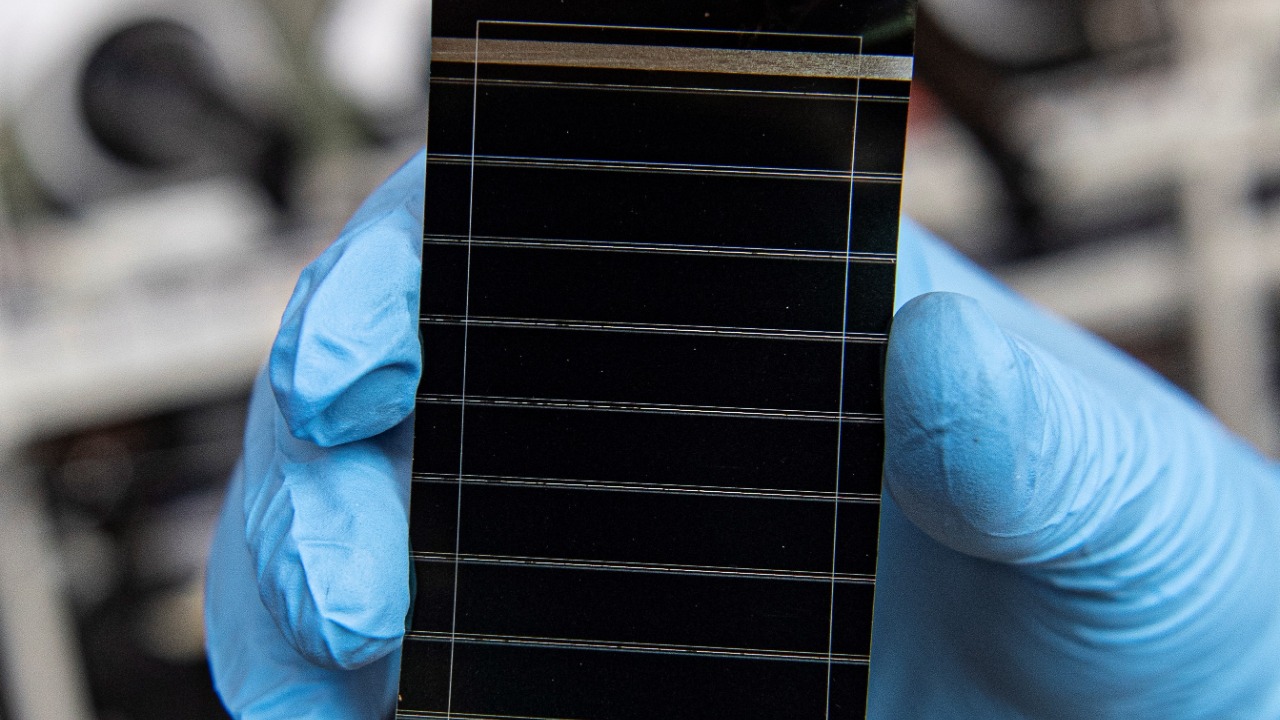

The material doing most of the heavy lifting in this transition is Perovskite, a class of compounds named for their distinctive crystal structure rather than a single chemical formula. In solar cells, Perovskite layers can be tuned to absorb different colors of light, deposited at low temperatures, and made extremely thin, which makes them ideal partners for silicon. Reporting on the latest lab and pilot devices notes that Perovskite solar cells offer much higher efficiency potential than conventional designs while still promising powerful, durable and efficient devices.

Part of the appeal is sheer versatility. Perovskite cells can be used by themselves in some applications, and they are ultra thin, meaning they can be sprayed onto flexible substrates or integrated into surfaces that would never host rigid silicon modules. As one analysis of the “wonder material” notes, Perovskite layers can be stacked with silicon in ways that push combined efficiency far beyond what either material could achieve alone. They can also be engineered to work with organic semiconductors or other exotic absorbers, opening a broad design space for future devices.

Tandem architectures and the 34.85% milestone

The most dramatic proof that stacking works comes from tandem cells that pair a Perovskite top layer with a silicon base. By vertically arranging multiple layers of semiconductor materials with varying bandgaps, Tandem cells can harvest high energy photons in the upper layer and lower energy photons deeper down, reducing the thermal losses that plague single junction devices. This architecture effectively sidesteps the Shockley–Queisser limit for a single absorber by turning one cell into a coordinated team of absorbers.

Performance numbers are now catching up with the theory. A detailed update on record devices reports that the best performing Perovskite tandem cells have reached an impressive 34.85% efficiency, a benchmark set by Longi in April 2025 and highlighted in Fig 1 of that analysis. When a commercial-scale manufacturer is pushing close to thirty five percent in the lab, it suggests that the technology is not just a scientific curiosity but a near term candidate for mass production, especially as process engineers refine how these delicate Perovskite layers are deposited on industrial lines.

Global race: Longi, Qcells and South Korea’s push

The sprint to harness these materials is now a global contest, with manufacturers and research institutes trading records and patents. Longi’s 34 figure has become a reference point for the industry, but it is far from the only player. A separate report notes that, Meanwhile, Qcells, a subsidiary of South Korea giant conglomerate Hanwha Corp, has set its own world record for the efficiency of advanced solar cells, underscoring how quickly the technology is moving from lab benches into corporate roadmaps.

South Korea has also entered the conversation through its public research infrastructure. Work at South Korea institutions, including The Korea Institute of Energy Resear, has focused on ultra thin Perovskite devices that could be cheaper to manufacture and easier to integrate into buildings or lightweight structures. These efforts complement earlier European advances, such as the Perovskite silicon tandem cells developed by Oxford PV, which have already surpassed the limits of conventional silicon cells according to analyses of how Oxford PV pushed the technology forward.

Beyond silicon’s ceiling: singlet fission and new physics

Even as Perovskite tandems dominate headlines, other researchers are probing more exotic routes to higher efficiency. One promising avenue is Singlet fission, a process in which a single high energy photon absorbed by an organic molecule splits into two lower energy excitations that can each generate an electron. Work from UNSW scientists explains that the theoretical ceiling for a standard silicon cell is about 29.4%, but Singlet fission offers a way past that barrier by effectively doubling the current from parts of the spectrum that would otherwise be wasted.

When sunlight hits certain organic semiconductors, the Singlet excited state can split into two triplet states, each capable of contributing to the electrical output if the device is designed correctly. Researchers argue that integrating such layers with silicon or Perovskite could yield cells that not only exceed traditional limits but also remain even cheaper and more powerful than today’s best modules. While these concepts are less mature than Perovskite tandems, they show that the field is not content with a single breakthrough and is instead exploring multiple routes to squeeze more work out of every photon.

Oxford PV and the path from lab to factory

Translating record efficiencies into real products is notoriously difficult, which is why the experience of Oxford PV matters. The company, a university spin off, has spent years turning Perovskite silicon tandem concepts into manufacturable devices. Reporting on its progress notes that Oxford PV has already demonstrated commercial Perovskite based solar cells with efficiencies around the high twenties and has invested in an annual 250 megawatt production line to bring those devices to market.

That experience is instructive for the new wave of record holders. It shows that moving from a champion cell on a postage stamp sized substrate to a bankable product involves solving issues of stability, encapsulation, and process control at scale. It also illustrates how partnerships between universities, spin offs, and large manufacturers can accelerate adoption. As Longi, Qcells and others chase higher numbers, they are likely to draw on similar models, blending cutting edge materials science with the kind of industrial discipline that can deliver millions of identical, high performing panels.

Why “beyond theoretical” efficiency matters on the ground

The practical impact of these efficiency gains is easiest to grasp in terms of land use and hardware counts. One industry analysis puts it bluntly: if you have 100 solar panels in the field, but you can get the same power output for only 60 or 80 of them, you have transformed the economics of a project. That framing, captured in a report that quotes the line “If you have 100 solar panels in the field, but you can get the same power output for only 60 or 80 of them,” highlights how higher efficiency can shrink solar farms or free up space on constrained rooftops.

Those gains translate directly into Reduced Space Requirements. Guidance for project developers stresses that Higher efficiency means fewer panels needed to achieve target output, which can cut mounting, wiring, and maintenance costs as well as land leases. In dense cities, it can make the difference between a building that can cover only a fraction of its load with rooftop solar and one that can approach full self supply. For utility scale projects, it can reduce the acreage required for a given megawatt rating, easing permitting battles and environmental concerns.

What comes next for solar’s “impossible” gains

Looking ahead, I see the current wave of breakthroughs as the beginning of a longer period of rapid iteration rather than a single step change. The combination of Perovskite, tandem architectures, and concepts like Singlet fission suggests that the industry is moving into an era where device physics, materials science, and manufacturing innovation reinforce each other. Analysts tracking the sector already describe a New Solar Material Is Pushing Efficiency Beyond Theoretical Limits moment, in which each new record forces planners to revisit assumptions about how much solar capacity is needed to decarbonize power systems.

There are still hurdles, from long term stability of Perovskite layers to the need for standardized testing that reflects real world conditions rather than idealized lab setups. Yet the trajectory is clear. As more manufacturers adopt tandem designs and refine their processes, the kind of efficiencies once reserved for world record tables will filter into mainstream products. At that point, the phrase “beyond theoretical” will feel less like a provocation and more like a reminder that in solar technology, the ceiling is often just a starting point for the next generation of engineers.

More from MorningOverview