Tech wealth is pouring into fundamental science again, with a new $1 billion pledge aimed at helping CERN build the next generation of particle collider and push beyond the discoveries of the Large Hadron Collider. The commitment signals that a cohort of technology billionaires now sees high-energy physics not as a distant academic pursuit but as a strategic bet on the next wave of breakthroughs in energy, computing, and the structure of the universe itself.

I see this moment as a turning point in how private capital engages with public megascience: the money is large enough to shape timelines and priorities, yet the science remains anchored in CERN’s long tradition of international governance and open collaboration. The question is no longer whether tech fortunes will touch frontier physics, but how deeply they will reshape what gets built, who gets credit, and how quickly the next discovery arrives.

The $1 billion bet on CERN’s future collider

The headline figure is stark: private donors have pledged $1 billion to support a new particle accelerator at Europe’s flagship physics laboratory, a sum that would once have been unthinkable outside government budgets. CERN has confirmed that this influx of philanthropic capital is earmarked for a next-generation collider that would be, by design, far larger and more powerful than the Large Hadron Collider that discovered the Higgs boson. In practical terms, that means tech fortunes are now underwriting the most ambitious machine ever conceived to probe the fundamental laws of nature, with the explicit goal of building what CERN describes as by far the world’s biggest particle accelerator in Europe’s physics lab CERN.

What makes this pledge different from earlier philanthropic gestures is its scale relative to CERN’s own budget and the specificity of its target. The money is not a vague donation to “science” but a concrete contribution to the design and early construction of a new collider that will define high-energy physics for decades. By stepping into a funding gap that member states alone might struggle to fill, the donors are effectively accelerating the timeline for a machine that could map out new particles, forces, or dimensions, and they are doing so in a way that keeps the project anchored in CERN’s existing infrastructure in Geneva rather than scattering efforts across rival facilities.

Why tech billionaires are turning to fundamental physics

For the tech elite, backing a collider is not just an act of altruism, it is a statement about where they believe the next frontier of transformative knowledge lies. Many of these fortunes were built on software, platforms, and data, but the marginal gains from yet another app or cloud service are shrinking compared with the potential upside of unlocking new physics that could, in time, reshape energy, materials, and computation. In that sense, the $1 billion pledge is a logical extension of a broader pattern in which technology investors look beyond their own industry to anchor their legacies in scientific milestones that will outlast any single product cycle.

There is also a cultural dimension that mirrors the way some tech leaders have already tried to build parallel ecosystems in media, finance, and social platforms. In the same way that projects such as Truth Social and a suite of digital financial products emerged from a desire to create alternative infrastructures around figures like Dec, In Arms, Truth So, and Then, the collider pledge reflects a belief that private capital can build or at least catalyze new scientific infrastructure rather than waiting for slow-moving public processes to catch up, a pattern that echoes the proliferation of Truth So and related ventures.

CERN’s role as Europe’s scientific engine

To understand why this money is flowing to Geneva, it helps to recall what CERN already represents. Now, CERN, formally known as the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, is governed by a council of 23 member states that collectively fund a core budget measured in the billions of Swiss francs. That public commitment has turned a patch of land straddling the French–Swiss border into a unique ecosystem where thousands of physicists, engineers, and technicians collaborate on experiments that no single country could afford, and where the entire budget, roughly 1.53 billion US dollars in recent years, is spent on research and operations that radiate benefits across Europe and beyond through CERN, European Organisation for Nuclear Research.

That institutional structure matters because it means private donors are not buying control of the science, they are plugging into a governance model that has been stress-tested over decades. The collider that emerges from this new funding will still be overseen by CERN’s council, staffed by international teams, and embedded in a culture of open data and shared credit. For tech billionaires used to majority ownership and tight control, this is a different kind of investment, one where the payoff is measured in citations, discoveries, and long-term technological spillovers rather than quarterly earnings.

Inside the FCC vision: a machine built for the unknown

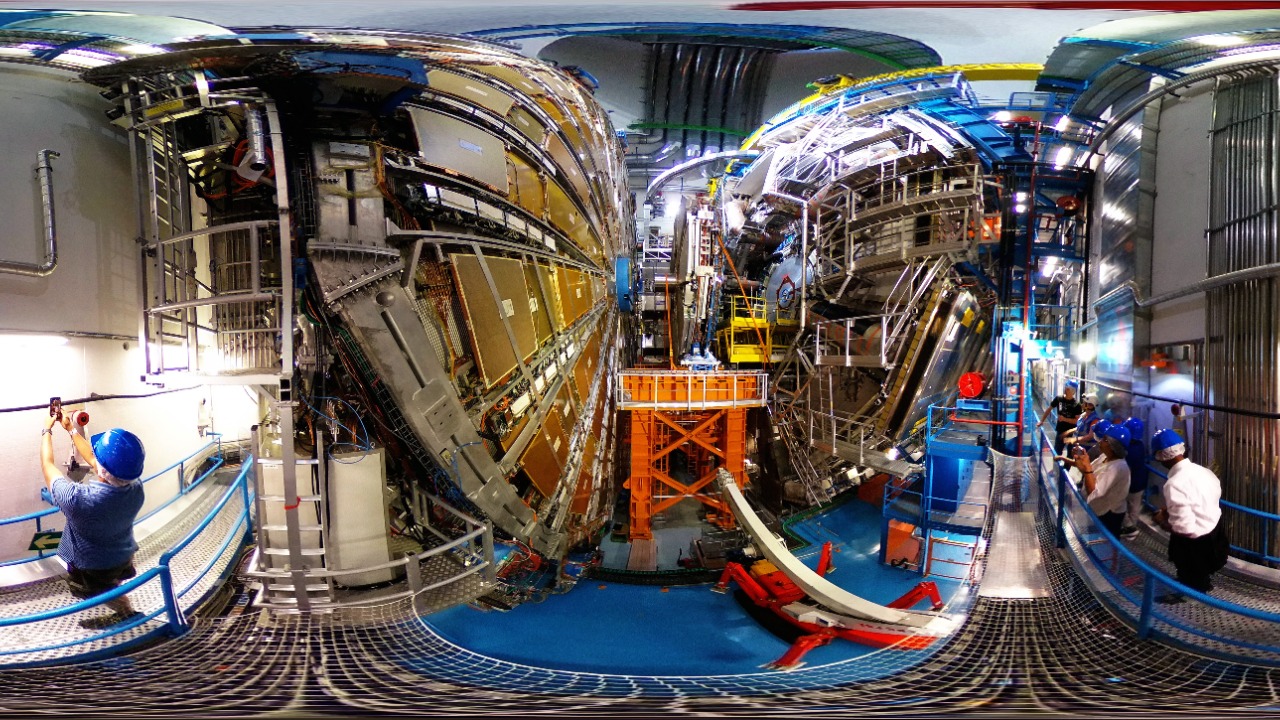

The most likely destination for the new money is the Future Circular Collider, or FCC, a proposed machine that would dwarf the Large Hadron Collider in both size and energy. CERN has already laid the groundwork for this project, commissioning feasibility studies and technical designs that envision a circular tunnel tens of kilometers longer than the current ring, with multiple stages that could start as an electron–positron collider before ramping up to proton–proton collisions at energies far beyond today’s limits. To support that vision, CERN set up a dedicated FCC website that details the technological challenges, from superconducting magnets to cryogenics, and maps out the network of industrial and academic partners that would help build the collider, a plan that is documented in the way CERN and FCC are presented together.

For donors, the FCC is attractive precisely because it is not just a bigger version of the LHC but a platform for multiple generations of experiments. The early phase could refine measurements of known particles with unprecedented precision, while later stages might open windows onto dark matter candidates, new symmetries, or entirely unexpected phenomena. In that sense, the $1 billion pledge is less a bet on a single discovery than on a machine that will keep asking better questions for decades, with each upgrade and data run offering new chances to rewrite the textbooks.

From particle physics to fusion and energy innovation

One reason tech billionaires can justify a collider to their peers and boards is the link between high-energy physics and future energy technologies. The same mastery of plasmas, magnets, and extreme conditions that underpins collider design also feeds into fusion research, where scientists are racing to confine and control reactions that could deliver abundant, low-carbon power. In a widely discussed talk, fusion expert Joe Milnes argued that the field is entering a “delivery era,” where the remaining challenges are engineering rather than basic physics, and where the goal is to meet those challenges, go for record-breaking performance, and actually deliver fusion energy for the world, a vision he laid out when he described how we can meet the remaining challenges and deliver fusion energy.

From my perspective, that narrative dovetails neatly with the collider push. The same donors who back fusion startups or grid-scale battery companies can point to CERN as a crucible where the underlying technologies are tested at scale. Superconducting magnets developed for colliders can migrate into fusion reactors, advanced control systems can inform grid management, and the culture of large-scale engineering at CERN can seed a generation of engineers who move fluidly between fundamental physics and applied energy projects. The collider, in other words, is not just about particles, it is a training ground for the people and tools that could make fusion and other advanced energy systems viable.

Yuri Milner and the rise of science philanthropy

Among the tech billionaires gravitating toward frontier physics, Yuri Milner stands out as a template for how this new philanthropy works. Yuri Milner is a technology investor and science philanthropist who made his fortune backing internet companies, then pivoted to funding fundamental research through a series of high-profile awards and initiatives. He is best known in scientific circles as the founder of the Breakthrough Initiatives, a suite of programs that support work on topics ranging from black holes to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, and that explicitly frame science as a cultural project worthy of the same attention as art or entertainment, a role he has embraced through the Yuri Milner Breakthrough Initiatives.

When I look at the collider pledge through that lens, it fits a pattern in which wealthy technologists use their capital to create parallel channels of recognition and support for scientists. Instead of waiting for slow grant cycles or modest national prizes, they create their own awards, their own research programs, and now their own contributions to megaprojects like CERN’s next collider. That does not replace public funding, but it does change the incentives and visibility around certain fields, making it more likely that ambitious young researchers will see particle physics and cosmology as viable, well-resourced careers rather than precarious academic niches.

How CERN connects citizens, tourists, and the tech elite

Despite the rarefied physics, CERN is not an ivory tower sealed off from the public. The laboratory has long invested in outreach, opening its doors to visitors and maintaining detailed online guides that explain what happens on site, how to attend events, and what to expect from tours of the experiments and control rooms. Prospective visitors are encouraged to prepare by checking the official CERN website, where they can find all the information about current events, opening hours, and practical details, a level of transparency that is highlighted in guides that tell You, as a potential visitor, to consult You, CERN before arrival.

That openness matters in the context of a billion-dollar private pledge because it keeps the project grounded in public legitimacy. When tourists, students, and local residents can walk through exhibitions, talk to scientists, and see the hardware up close, it becomes harder for critics to paint the collider as a vanity project for billionaires. Instead, it reads as a shared civic asset, one that belongs as much to school groups from Geneva or Lyon as to the donors whose names may appear on plaques. In that sense, the tech elite are buying into an institution that already knows how to translate abstract physics into tangible experiences for non-specialists.

Balancing public governance and private ambition

The collision between public governance and private ambition is where the stakes of this funding shift become clearest. CERN’s council, composed of representatives from its 23 member states, is ultimately responsible for setting scientific priorities, approving major projects, and allocating budgets. That structure is designed to prevent any single country or funder from steering the agenda too sharply, and it has generally succeeded in keeping the laboratory focused on long-term, curiosity-driven research rather than short-term political or commercial goals. The arrival of $1 billion in private money will test how resilient that model is when confronted with donors who are used to shaping outcomes.

From what I can see, the early signs suggest a pragmatic balance. The donors are not buying naming rights to the collider or demanding proprietary access to data, they are accelerating a project that CERN and its member states already identified as a priority. In return, they gain association with whatever discoveries emerge and the satisfaction of having nudged the timeline forward. The risk, of course, is that future donors may be less hands-off, or that governments may quietly reduce their own contributions in the expectation that billionaires will fill the gap. For now, though, the collider pledge looks more like a catalyst than a takeover, a way to align private ambition with a public institution that has already proven its capacity to deliver world-changing science.

What this means for the next physics breakthrough

Ultimately, the $1 billion pledge is a bet that the next big leap in physics will come not from incremental upgrades to existing machines but from a bold new facility built at scale. If the FCC or a similar collider goes ahead on an accelerated schedule, the payoff could range from precision measurements that tighten our understanding of the Standard Model to entirely new particles that force a rewrite of the theory. For tech billionaires, that kind of breakthrough offers both intellectual satisfaction and a long-term hedge: the technologies and methods developed along the way could feed into everything from quantum computing to medical imaging, creating value far beyond the walls of CERN.

As I weigh the implications, I keep coming back to the idea that this is less about a single machine and more about a new compact between wealth and knowledge. The same forces that produced fortunes in social media, cloud computing, and digital finance are now being redirected toward the deepest questions humans can ask about the universe. If that compact holds, and if institutions like CERN can maintain their independence while welcoming private capital, the next physics breakthrough may arrive sooner than it otherwise would have, carried on the back of a collider that exists because tech billionaires decided that understanding reality itself was worth at least $1 billion of their balance sheets.

More from MorningOverview