China is now accused of doing what Washington spent years trying to prevent: building its own version of the world’s most advanced chipmaking tool and edging closer to independence from foreign semiconductor technology. Reports point to a covert effort to replicate extreme ultraviolet lithography, the EUV systems that sit at the heart of cutting edge chips, suggesting that the global chip war has entered a far more volatile phase.

If confirmed, a Chinese EUV breakthrough would not only challenge the export controls that have defined United States strategy, it would also test the dominance of ASML, the Dutch company whose machines are widely described as the most complex devices ever built. I see this moment as a stress test for the entire semiconductor order, from smartphone makers to military planners who rely on advanced logic and memory chips.

How EUV became the crown jewel of chipmaking

The stakes around EUV are so high because this technology is the bottleneck for the most advanced chips, the kind used in flagship phones, high end data center accelerators, and state of the art weapons systems. Without access to advanced lithography, China cannot mass produce modern chips at 5 nm, 3 nm, or 2 nm, the nodes that define the current performance frontier for everything from premium Android devices to top tier AI servers, as highlighted in an analysis that bluntly states that without advanced lithography China cannot make modern chips. EUV tools solve a simple but brutal physics problem, they use extremely short wavelength light to etch ever finer patterns onto silicon wafers, enabling transistor densities that older deep ultraviolet systems cannot match.

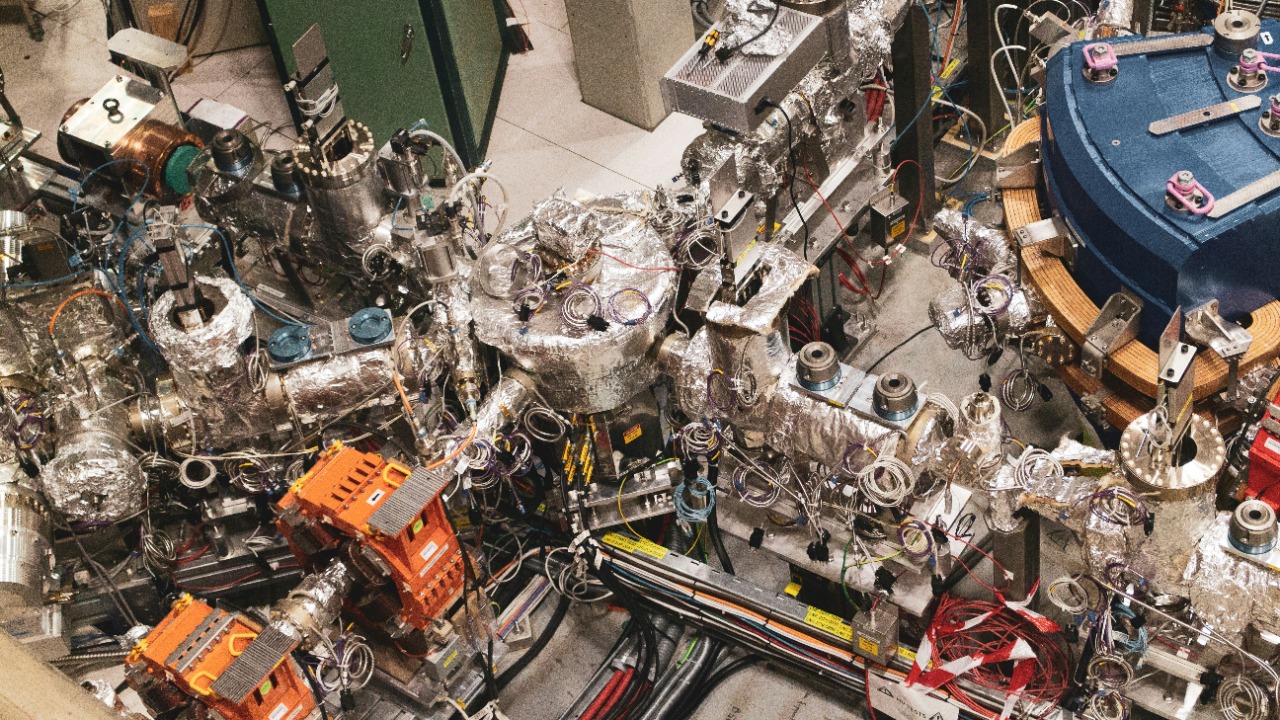

ASML sits at the center of this ecosystem, combining optics, software, materials science, and precision mechanics in a way that no rival has yet replicated. One detailed overview describes how ASML’s platforms are so intricate that no single engineer fully understands them, calling these EUV systems “engineering marvels” and “the most complex devices ever built by humankind,” a description that underlines why the company launched a science project in China to scout new talent for its work on these machines. That complexity is precisely what Washington has tried to weaponize, betting that export controls on a single Dutch supplier could slow China’s march toward semiconductor self sufficiency.

Inside the reports of a covert Chinese EUV lab

The latest wave of reporting suggests that China did not accept that bet. Instead, it allegedly built a covert research program dedicated to reverse engineering an EUV lithography tool, operating behind layers of secrecy that included fake employee identities to keep the project off the radar. According to one detailed account, China may have set up a hidden lab where staff were given falsified IDs so that the effort to copy an EUV scanner could proceed without detection, with the goal of producing prototypes that might be ready for testing around 2028, a timeline that underscores how long it can take to turn a lab concept into a production ready EUV lithography tool.

A companion report adds technical color, describing how China’s alleged EUV scanner appears to mimic key subsystems of ASML’s architecture, including laser produced plasma light sources and complex optics that must operate in a vacuum. That account notes that the Chinese design is not yet ready for volume production, but it still frames the project as a serious attempt to replicate ASML’s laser produced plasma (LPP) approach and other critical elements of an EUV scanner, suggesting that China’s engineers have at least mapped out the contours of China’s alleged EUV scanner. If accurate, that would mean the country has crossed a psychological threshold, moving from aspirational talk about catching up to a concrete, if still experimental, machine.

From reverse engineering to a working prototype

What makes these reports more than rumor is the growing evidence that China has already assembled at least one working prototype of an EUV lithography machine. One technical analysis describes how Chinese teams reverse engineered the most advanced chipmaking machine in the world, combining domestic talent with painstaking disassembly and study of imported parts to build what is described as China’s most advanced chipmaking system, a project that explicitly involved China reverse engineers the most advanced chip making machine. The same account stresses that this is still a research platform rather than a factory workhorse, but the fact that it can reportedly generate EUV patterns at all is a major milestone.

Another report, framed around the geopolitical shock value, states that China has just built the one machine the United States spent a decade trying to keep out of its hands, describing a working prototype of an EUV lithography machine that has already been powered on and tested. That description emphasizes the word “prototype,” underscoring that this is not yet a commercial product but still a functioning research tool that could be refined into a production system, a step that would validate years of effort to create a domestic prototype EUV lithography machine. Taken together, these accounts suggest that China has moved beyond theoretical reverse engineering and into the messy, iterative world of real hardware.

The role of ex‑ASML talent and industrial espionage claims

One of the most sensitive threads in this story is the role of former ASML employees in accelerating China’s progress. According to a detailed reconstruction, ex ASML workers helped reverse engineer state of the art chipmaking machines, giving China a shortcut to understanding the intricate interplay of optics, software, and mechanics that define EUV systems. That report cites two Reuters sources who say China now has a prototype EUV chipmaking machine, though it has not yet produced a working chip, and it stresses that this effort has brought the country far closer than previously thought to independence from foreign technology, a leap that hinges on the expertise of ex ASML workers.

Separate commentary has long warned that Chinese engineers have tried to reverse engineer ASML’s deep ultraviolet, or DUV, machines as a stepping stone to EUV, arguing that industrial policy, national security, and technological sovereignty are now converging in Beijing’s semiconductor strategy. One widely shared analysis notes that Chinese engineers reportedly tried to buy and study older ASML systems to learn the technology, and it uses that history to argue that China’s leadership sees chipmaking as a core sovereignty issue, not just a commercial one, a view captured in a discussion that explicitly links Chinese engineers reportedly tried to reverse engineer ASML’s DUV machine. The emerging EUV prototype looks like the logical, if controversial, culmination of that long running campaign to absorb foreign know how.

ASML’s unique position and China’s long game

To understand why China would go to such lengths, it helps to look at ASML’s singular role in the chip industry. A detailed profile explains how ASML sits at a rare intersection of physics, software, and geopolitics, with its EUV systems effectively forming a chokepoint in the global supply chain. That same analysis notes that ASML’s machines are so complex that they require a global network of suppliers and that the company has had to carefully manage the number of systems sold to Chinese firms, a balancing act that reflects both commercial demand and political pressure, as described in a piece that highlights how ASML’s machines and China’s semiconductor ambition intersect.

China’s response has been to play a long game, combining domestic research, talent recruitment, and reverse engineering to chip away at that chokepoint. Earlier this year, ASML itself launched a science project in China to discover new talent in physics and engineering, a move that underscores how deeply intertwined the Dutch company already is with Chinese universities and labs, even as export controls tighten. The description of that initiative, which portrays ASML’s platforms as the most complex devices ever built and frames the project as a way to inspire Chinese students to tackle those challenges, shows how the same ecosystem that nurtures collaboration can also create pathways for knowledge transfer that Beijing can later fold into its own science project in China. In that sense, the alleged covert lab is not an isolated outlier but part of a broader strategy to reduce reliance on a single foreign supplier.

How China has squeezed more from older ASML tools

Even before the EUV prototype reports surfaced, China had been pushing the limits of older lithography equipment to keep its chip ambitions alive. According to people familiar with the matter, Chinese fabrication plants producing advanced smartphone and AI chips have been upgrading older ASML machines with new process tricks and design optimizations, effectively boosting AI chip output by focusing on performance per chip rather than shrinking physical dimensions. That approach, described in a discussion of how Chinese fabrication plants boost AI chip output, shows how far Chinese engineers have gone to stretch DUV tools beyond their intended design envelope.

This strategy has bought Beijing time, allowing domestic chipmakers to stay in the game for AI workloads even without EUV. By stacking more transistors through advanced packaging, optimizing circuit layouts, and tailoring chips for specific AI models rather than generic benchmarks, Chinese firms have managed to field competitive accelerators for tasks like large language models and computer vision. Yet there is a ceiling to what can be done with older tools, and the reports of a homegrown EUV prototype suggest that China is no longer content to live within those constraints, especially as export controls tighten around high bandwidth memory, advanced GPUs, and other components that depend on leading edge AI chip output.

Military and AI stakes in the chip wars

The implications of a Chinese EUV breakthrough extend far beyond consumer electronics. A detailed review of the geopolitics of AI and semiconductors notes that while much attention is currently focused on high density and high performance cutting edge semiconductor nodes below 7 nm, chips built on older processes remain critically important for military forces worldwide, powering everything from radar systems to logistics networks. That analysis argues that control over both advanced and legacy nodes shapes the balance of power in AI enabled warfare, a point captured in the observation that while much attention is currently focused on high density and high performance cutting edge semiconductor nodes below 7 nm, chips built on older processes remain critically important. If China can master EUV, it would gain more control over both ends of that spectrum.For the United States and its allies, that possibility raises hard questions about the effectiveness of current export controls, which have centered on blocking EUV tools and the most advanced GPUs while leaving large swaths of the semiconductor stack relatively open. A Chinese EUV prototype, even one that is years away from mass production, suggests that the window for using ASML as a chokepoint may be closing. It also hints at a future in which Chinese fabs can produce high end AI accelerators and secure communications chips without relying on foreign lithography, eroding one of Washington’s most powerful levers in the broader chip wars.

What a Chinese EUV prototype really changes

It is important to separate hype from reality. The reports are clear that China’s EUV effort is still at the prototype stage, with no evidence yet of working chips rolling off a production line. One account explicitly notes that the prototype EUV chipmaking machine has not produced a working chip, even as it credits the project with bringing China far closer to independence from foreign tech, a nuance that matters when assessing the impact of a prototype EUV chipmaking machine. Moving from a lab tool to a reliable, high throughput production system will require years of refinement, supply chain building, and process integration.

Yet even at this early stage, the psychological and strategic impact is significant. For Beijing, the existence of a prototype validates its long running bet on talent, reverse engineering, and covert research, showing that export controls can be bent if not fully broken. For Washington and its partners, the news is a warning that chokepoints are perishable, especially when they rest on a single company in a small European country. I see this as the moment when the chip war shifts from blocking access to one machine to a broader contest over ecosystems, from materials and optics to software and packaging, where no single export license can fully contain the ambitions of a state willing to pour resources into reverse engineering the most advanced chip making machine.

More from MorningOverview