The Moon has long been treated as a geologically dead world, a frozen relic that finished erupting billions of years ago. A wave of new data is now challenging that assumption, pointing instead to a body that may still be reshaping itself in subtle but significant ways. From fresh-looking lava to shifting ridges and mysterious interior signals, evidence is piling up that volcanic and tectonic forces on our nearest neighbor never fully went quiet.

I see a consistent pattern emerging from these findings: the Moon is cooler and quieter than Earth, but it is not inert. Clues from its surface, its interior structure and even its far side suggest lingering heat and motion that could still be driving small eruptions or quakes today. That possibility is reshaping how scientists think about rocky worlds across the Solar System and how mission planners prepare to send people back to the lunar surface.

The old picture of a dead Moon is breaking down

For decades, textbooks framed the Moon as a world whose volcanic story ended billions of years ago, with dark basalt plains as the fossilized remains of a fiery youth. That view rested on Apollo samples and crater counts that pointed to intense eruptions early on, followed by a long, cold silence. In that narrative, the Moon cooled quickly because it is small, lost its internal heat, and left behind a static landscape that only meteorites could modify.

Recent work on volcanism on the Moon has begun to erode that simple timeline, showing that the story is more complicated and more drawn out. Researchers now recognize not only the familiar basaltic plains but also pyroclastic deposits and other explosive features that point to a wider range of eruption styles. The same analyses emphasize that, although the surface appears quiet today, pockets of heat and partially molten rock may still persist under the Lunar crust, keeping the door open for ongoing activity.

Young lava and irregular mare patches hint at recent eruptions

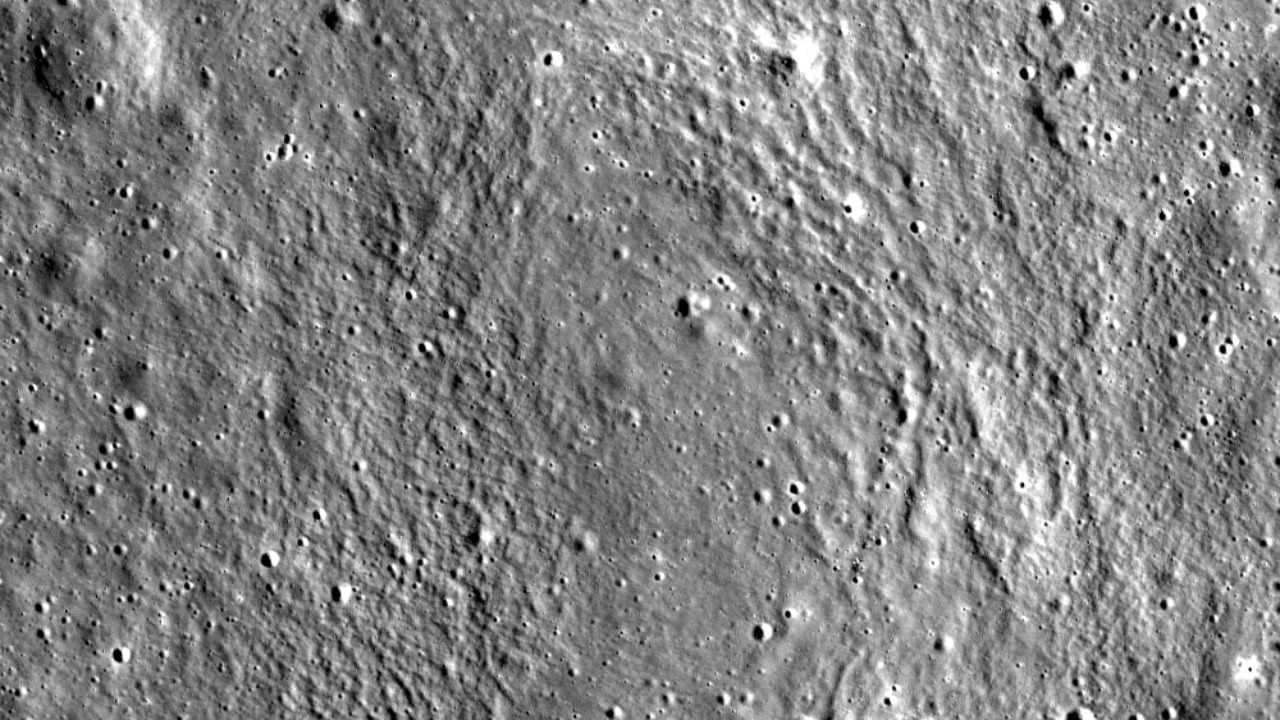

One of the clearest challenges to the old, tidy timeline comes from patches of terrain that look far too fresh to be ancient. High resolution imagery highlights smooth, dark flows and sharp-edged features that resemble young lava fields on Earth more than battered, billion-year-old rock. These surfaces lack the dense overprint of impact craters that would be expected if they had sat exposed for eons, which suggests that some eruptions occurred much later than scientists once assumed.

Visualizations of Young Lava On The Moon underscore how these flows cut across older terrain, implying that molten rock reached the surface relatively recently in geological terms. At the same time, small features known as Irregular mare patches, or IMPs, have been flagged as potential signs of recent volcanic activity, with their crisp boundaries and unusual textures standing out against the surrounding plains. Together, these clues suggest that the Moon’s volcanic engine did not simply switch off billions of years ago, but instead faded gradually, with isolated eruptions that may have persisted into the more recent past.

Chinese samples and the 120 M year surprise

The strongest evidence that the Moon stayed active far longer than expected comes from rocks physically returned from its surface. Samples collected by a Chinese mission from a relatively young lava plain have been dated to only a few hundred million years old, dramatically extending the known lifetime of lunar volcanism. That result forces a rethink of how such a small body could keep enough heat in its interior to melt rock and feed eruptions so late in its history.

Analyses of these samples, including work highlighted in a study that described how the Moon was still erupting while dinosaurs thrived on Earth, show that the most common rock on the surface is basalt and that some of it formed surprisingly late, with one line of evidence pointing to activity roughly 120 M years ago, a timeframe described as “Million Years Ago” in the context of the Moon’s evolution. Researchers writing about how Irregular mare patches might connect to these young basalts argue that such late eruptions demand new models of how the Moon developed and retained heat. I see those findings as a direct challenge to the idea that the interior froze solid early on.

Far side eruptions and the mystery of Lunar asymmetry

For years, the Moon’s far side was treated as a quiet, heavily cratered contrast to the familiar near side with its dark seas of lava. That picture is now changing as orbital data reveal that the hidden hemisphere also bears the marks of intense volcanism. Researchers using orbital images have identified Major volcanic eruptions on the far side, showing that The Moon’s supposedly bland hemisphere once hosted large lava flows and complex volcanic structures comparable to those on the near side.

These discoveries tie into a broader effort to understand Lunar Asymmetry, the puzzling difference between the Moon’s two faces that shows up in its crust thickness, composition and gravity field. Detailed gravity mapping, built from more than 30,000 images of another body and applied to the Moon, has helped scientists infer how heavy materials sank and lighter ones rose as the interior evolved. I read that work as a sign that the far side’s volcanic history is not an afterthought but a key to understanding how the entire Moon cooled, where residual heat might still be trapped, and why some regions may remain more active than others.

Ridges, quakes and a Moon on the Move

Volcanism is only part of the story, because the Moon’s surface is also being reshaped by tectonic forces that hint at a restless interior. A new generation of high resolution topographic maps has revealed networks of ridges and scarps that cut across craters and lava plains, indicating that the crust is still being squeezed and shifted. These structures are not just ancient scars; some of them appear crisp and relatively unweathered, suggesting that they formed in the recent geological past.

One study described the Moon as being on the Move, with Surprising New Ridges Reveal Recent Activity that may still be ongoing. The authors posed the question “What is this?” to capture how unexpected it is to see such youthful tectonic landforms on a supposedly frozen world. When I look at those ridges alongside evidence of moonquakes, I see a body that is still adjusting to internal and external stresses, from cooling and contraction to tidal forces, in ways that could open or close pathways for magma at depth.

Is the Moon still geologically active today?

The central debate now is not whether the Moon was active more recently than once thought, but whether it is still active right now. Some scientists argue that the combination of young lava, fresh tectonic features and ongoing quakes points to a world that has not yet fully shut down. Others caution that even if the crust is moving, the interior might only be warm enough for slow deformation, not for new eruptions that would reach the surface in our lifetimes.

Work synthesizing these clues has led researchers to ask directly whether the Moon is still geologically active, with one analysis noting that “But we’re seeing that these tectonic landforms have been recently active in the last billion years and may still be active today.” That same work points out that if current activity is confirmed, it would mean some faults could slip every few million to 15 million years, a slow but real drumbeat of change. I read that as a cautious but clear statement that the Moon’s story is not finished, even if its pace is glacial by human standards.

Signals from inside: something is moving

Surface features are only half the evidence; the other half comes from the Moon’s interior, where subtle motions can betray lingering heat and structural change. Seismometers and gravity measurements have already shown that the interior is layered, with a core, mantle and crust that respond differently to tidal forces. New analyses of those signals suggest that parts of the interior may still be shifting in ways that are not yet fully understood.

A recent explainer on how Something Is Moving Inside the Moon, Scientists Discovered describes “something happening inside the moon” that is not a dramatic surface shift but a quieter internal process. The video, dated Jan in its description, emphasizes that these changes are subtle yet real, hinting at ongoing adjustments in the deep interior. To me, those findings dovetail with the tectonic and volcanic clues at the surface, reinforcing the idea that the Moon is still cooling and evolving rather than sitting in perfect equilibrium.

Dinosaurs, basalts and a long volcanic tail

One of the most striking narrative hooks in this research is the overlap between lunar eruptions and life on Earth. While dinosaurs roamed our planet, the Moon appears to have still been venting lava, extending its volcanic era far beyond what early models predicted. That temporal overlap is not just a curiosity; it shows that small rocky bodies can sustain internal heat and magmatic activity for billions of years, which has implications for worlds far beyond our own system.

Reporting on how the moon had active volcanoes while dinosaurs were still present notes that basalt, a well known volcanic rock, dominates the lunar surface and that some of it formed relatively late, with evidence of eruptions continuing into the last few hundred million years. That same work points to a sample returned from the lunar surface in 2020 as a key piece of the puzzle. I see this “long volcanic tail” as a reminder that planetary cooling is not a simple on off switch, and that even modest residual heat can drive sporadic eruptions long after the main phase of activity has faded.

Far side discoveries and the Nature and Science connection

The far side’s volcanic story has gained extra weight from the way new findings have been vetted and published. Detailed analyses of far side lava deposits and associated structures have been scrutinized in multiple venues, reflecting both their novelty and their importance for understanding the Moon as a whole. The work shows that the far side is not just a passive receiver of impacts but a region with its own complex volcanic and tectonic history.

A report on how volcanoes once erupted on the far side of the moon notes that the findings were published in the Nature and Science journals on Friday, underscoring the level of scrutiny and interest they attracted. That dual publication highlights how central the far side has become to debates about Lunar evolution, from crust formation to the distribution of radioactive elements that could keep the interior warm. In my view, it also signals that any future model of lunar activity that ignores the far side is incomplete by definition.

What lingering heat means for future missions

All of this evidence, from young lava and IMPs to ridges, quakes and interior motion, converges on a simple but powerful idea: the Moon still has pockets of heat and perhaps even small reservoirs of melt. For mission planners, that is not an abstract curiosity but a practical concern. Active or recently active faults could pose seismic risks to landers and habitats, while residual heat might influence where ice is stable in permanently shadowed regions that future astronauts hope to mine.

Analyses of Lunar eruptions and their implications for how the Moon developed stress that understanding the timing and distribution of volcanism is essential for predicting where resources and hazards might lie. Studies that describe the Moon as being on the move, with Surprising New Ridges Reveal Recent Activity, explicitly connect these findings to how we plan future moon missions. As I see it, the emerging picture of a still evolving Moon is not just scientifically exciting, it is a roadmap for where and how humans can safely explore our closest neighbor in the decades ahead.

More from MorningOverview