Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is giving planetary scientists something they almost never get: a fresh sample of material from another star system, lit up in ultraviolet like a forensic lamp on a crime scene. By catching the comet’s faint UV glow, spacecraft scattered across the Solar System are starting to tease out what this visitor is made of and how it behaves, turning a single snapshot into a chemical and physical profile of alien ice.

I see that ultraviolet portrait as more than a pretty picture. It is a diagnostic tool that can separate water from carbon dioxide, trace elusive hydrogen, and reveal how a primordial “time capsule” from deep space responds to sunlight, all of which helps researchers test ideas about how comets form around other stars and how typical, or strange, 3I/ATLAS really is.

Why 3I/ATLAS matters as a “time capsule” from another star

Interstellar objects are rare enough that each one functions like a one-off experiment, and 3I/ATLAS arrives with a reputation as a pristine relic. Spanish researchers have described it as a primordial “time capsule,” arguing that its ices and dust preserve conditions from the system where it formed, long before it was ejected into interstellar space and eventually wandered into ours. In that framing, every molecule released from 3I/ATLAS as it warms is a clue to what newborn planets and comets might look like or how they formed around other suns, a point underscored by work that highlights how The European Space Agency and ground-based teams rushed to capture its early behavior.

That sense of urgency reflects how little we know about material forged around other stars. Only two confirmed interstellar visitors, 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov, have passed through before, and both left scientists with more questions than answers about their composition and origin. By contrast, 3I/ATLAS is being tracked by a coordinated network of observatories and spacecraft, from Mars orbit to the outer Solar System, which gives researchers a chance to compare its chemistry and activity with local comets in far more detail than was possible for its predecessors, and to see whether this “time capsule” looks familiar or fundamentally foreign.

How NASA’s ATLAS survey and early imaging set the stage

Before any ultraviolet spectrograph could dissect 3I/ATLAS, someone had to spot it, and that job fell to a system built to watch for hazards closer to home. The object was first identified by the NASA funded ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial impact Last Alert System), a survey designed to scan the sky for potentially dangerous near Earth objects but sensitive enough to catch a faint, fast moving interstellar comet on its inbound trajectory. That early detection meant astronomers could calculate its path, predict its close passes by Mars and Earth, and line up a suite of instruments to observe it from multiple vantage points, a strategy detailed in a broader overview of how scientists are viewing the comet through multiple lenses.

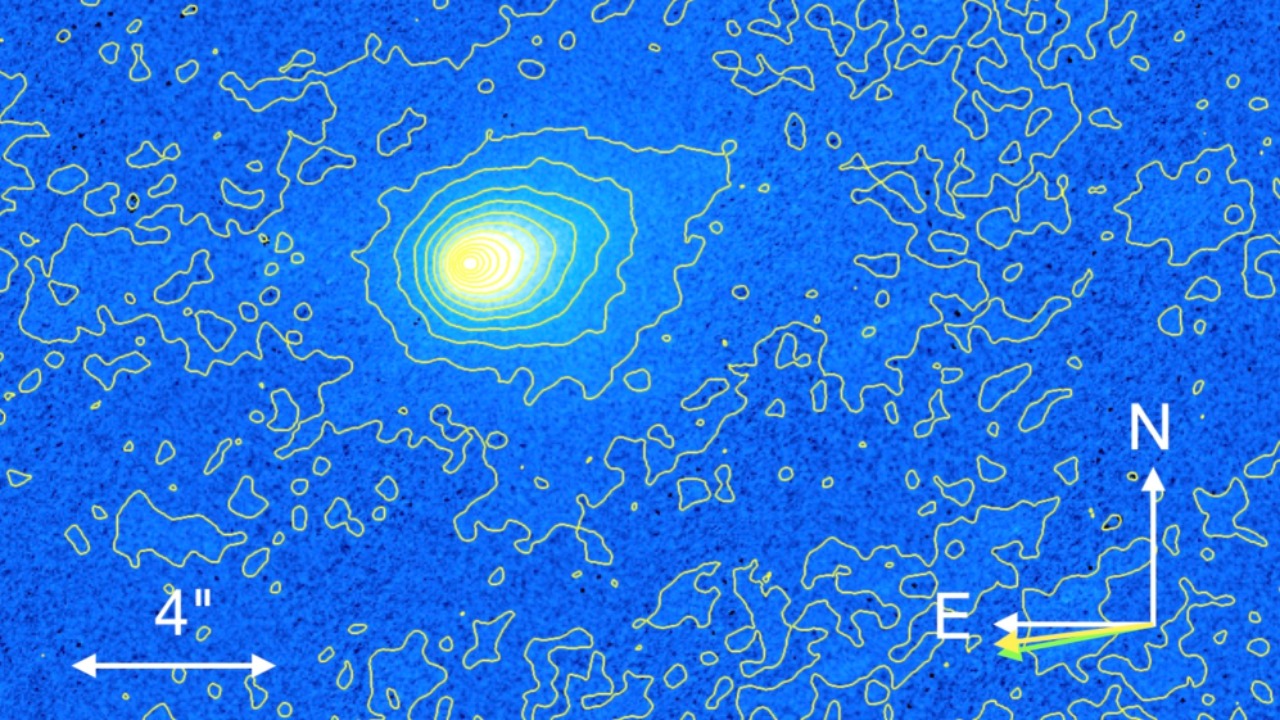

Once the orbit was nailed down, imagers began to build the first composite portraits. One key view was created by stacking a series of images taken on Sept. 16, 2025, as 3I/ATLAS was racing toward Mars, a technique that sharpened the comet’s faint smudge against the starfield and helped define the orientation of its tail relative to the Sun and “Solar system north.” That same campaign emphasized how the ATLAS discovery allowed planners to schedule follow up observations from missions like Lucy and others, as described in a focused discussion of how This image was made and why that geometry matters for interpreting the comet’s activity.

Mars orbiters turn toward an interstellar visitor

With the comet sweeping past Mars, spacecraft already in orbit around the planet suddenly found themselves in prime position to study an object from another star system. NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and other assets captured visible light images that showed 3I/ATLAS as a faint, moving blur against the background, but the real prize came from the MAVEN mission, which is normally focused on the Martian atmosphere. Over the course of 10 days starting Sept. 27, MAVEN used its Imaging UltraViolet Spectrograph to record the comet in two distinct ways, providing both a global view of its surrounding gas and a more targeted look at specific emissions, as described in a detailed account of how NASA’s Mars spacecraft capture images of the interstellar visitor.

Those observations were not just opportunistic snapshots. The MAVEN team adjusted the spacecraft’s pointing and observing cadence so that the Imaging UltraViolet Spectrograph could separate the comet’s own emissions from the Martian background, a technically demanding maneuver given the object’s speed and faintness. In a closer look at the campaign, mission scientists explain how MAVEN tracked 3I/ATLAS over that 10 day window and why those ultraviolet data are only the surface of their analysis, hinting at deeper work to extract composition and outgassing rates from the spectra.

Europa Clipper’s ultraviolet snapshot and what it can show

While Mars orbiters watched from the inner Solar System, another spacecraft, NASA’s Europa Clipper, turned its attention to 3I/ATLAS from much farther out. The Europa Clipper spacecraft used its Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) to capture a new ultraviolet image of the comet, a view that is especially valuable because it samples different lighting conditions and distances than the Mars based observations. Mission updates describe how The Europa Clipper team seized the chance to test UVS on a moving, diffuse target while the spacecraft cruises toward Jupiter’s moon Europa.

That ultraviolet snapshot is central to the current excitement because it can directly probe the gases streaming off the comet’s nucleus. By measuring how the comet glows at specific UV wavelengths, UVS can distinguish between emissions from water products like hydrogen and oxygen and those from other volatiles such as carbon dioxide, which is crucial for understanding the balance of ices in 3I/ATLAS. Scientists involved in the campaign have said they are hopeful that this new view, combined with Earth based and other spacecraft data, will help reveal whether the comet’s composition matches typical Solar System comets or stands apart, a point emphasized in reporting on how Earth based telescopes and Europa Clipper are working in tandem.

Ultraviolet light as a chemical fingerprint

Ultraviolet observations matter because they turn the comet’s coma into a kind of spectral barcode. When sunlight hits 3I/ATLAS, it breaks apart molecules like water and carbon dioxide into fragments that fluoresce at characteristic UV wavelengths, allowing instruments to infer what is present even if the original molecules are hard to see directly. Researchers studying 3I/ATLAS have already reported that its carbon dioxide to water ratio appears larger than usual compared with many Solar System comets, a finding highlighted in a briefing where NASA shared images and early compositional clues from the interstellar comet.

Detecting water itself in the ultraviolet is a subtle business, because Earth’s atmosphere absorbs most UV light before it reaches the ground. That is why space based observatories are so important. In one key study, astronomers used the Swift observatory to pick up a faint ultraviolet signal from 3I/ATLAS, describing how Catching that whisper of ultraviolet light required rapid targeting and careful calibration to separate the comet’s emission from background noise. Their analysis, which links the UV signature to water related activity, is detailed in a report on how Catching that signal from ATLAS pushed Swift’s capabilities.

Water activity where none was expected

One of the most intriguing results so far is that 3I/ATLAS appears to show water related activity at distances from the Sun where such behavior is usually weak or absent. Physicists analyzing the UV data have described this as “Water activity where none was expected,” arguing that the comet’s outgassing pattern does not match the standard picture in which water only dominates closer in while more volatile ices drive activity farther out. That conclusion, drawn from the strength and distribution of hydrogen emissions in the ultraviolet, is laid out in a study that frames the comet as a kind of “message in a bottle” from interstellar space, a metaphor explored in depth in an analysis of Water activity and what it implies about ATLAS.

If that interpretation holds, it would suggest that 3I/ATLAS either formed in a region of its home system with different temperature and pressure conditions than those that shaped most Solar System comets, or that its surface has evolved in a way that exposes water rich layers earlier in its approach to the Sun. Either way, the ultraviolet data are forcing modelers to revisit assumptions about how interstellar comets should behave, and to consider whether our local sample of icy bodies is representative or biased. The fact that this insight comes from UV signatures that are normally invisible from the ground underscores how crucial space based spectroscopy is for decoding the physics of alien ice.

Connecting cometary UV science to the hunt for missing matter

The same ultraviolet techniques now being applied to 3I/ATLAS have already transformed a very different cosmic mystery: the search for the universe’s “missing” normal matter. Astronomers trying to account for all the ordinary, baryonic matter predicted by cosmological models have long suspected that a significant fraction lurks in diffuse, ionized gas between galaxies, but that material is almost impossible to see directly. One breakthrough came from realizing that if a cloud of ionized hydrogen sits between Earth and a bright UV source, that hydrogen will absorb specific wavelengths, leaving a telltale imprint in the spectrum, a strategy described in detail in an account that begins, “Luckily, if a cloud of ionized hydrogen sits between Earth and a source of ultraviolet light,” and goes on to explain how researchers have been hunting for this ionized gas, as summarized in a report that notes how Luckily that absorption trick helped close the normal matter budget.

In that context, 3I/ATLAS becomes another test case for how UV light can reveal otherwise hidden structures. Instead of tracing tenuous gas between galaxies, scientists are now using similar spectral fingerprints to map the distribution of water, carbon dioxide, and other volatiles in a single, compact object from another star system. The techniques are different in detail, but the logic is the same: let ultraviolet photons do the hard work of interacting with matter, then read out the results as a pattern of emission and absorption lines. By refining those methods on a bright, nearby target like 3I/ATLAS, researchers can sharpen the tools they will later apply to fainter, more distant interstellar visitors and to the diffuse gas that threads the cosmos.

Multiple spacecraft, one coordinated experiment

What makes the current campaign on 3I/ATLAS unusual is the sheer number of platforms involved, each contributing a different piece of the puzzle. From Mars orbit, MAVEN and other spacecraft are capturing both visible and ultraviolet views that show how the comet’s coma and tail evolve as it sweeps past the planet, as detailed in mission updates on how Over the course of 10 days starting Sept. 27, MAVEN recorded the comet in two unique ways. Farther out, Europa Clipper’s UVS is adding its own ultraviolet snapshot, while Earth based telescopes monitor brightness changes and dust production, creating a layered dataset that spans wavelengths and vantage points.

That coordination is not accidental. Scientists have explicitly framed 3I/ATLAS as an opportunity to run a Solar System wide experiment on an interstellar object, combining the strengths of each mission. One overview of the campaign notes how Lucy, en route to the Trojan asteroids of Jupiter, joined the observing effort alongside Mars orbiters and other spacecraft, as part of a broader strategy to view the comet through Lucy and a suite of other instruments. By stitching together these perspectives, researchers can cross check measurements of gas production, dust behavior, and compositional ratios, reducing the risk that any single instrument’s limitations will skew the picture of what lies inside the comet.

What the UV snapshot hints about composition and origin

Pulling these threads together, the emerging ultraviolet portrait of 3I/ATLAS points to a comet that, in some ways, looks familiar and, in others, stands out. Visible light images from across the Solar System show a classic cometary appearance, with a diffuse coma and tail that behave much like those of long period comets from the Oort Cloud, a similarity highlighted in coverage of how Interstellar comet ATLAS looks and behaves like a comet in images taken by the Mast camera and other instruments. Yet the UV data, particularly the elevated carbon dioxide to water ratio and the unexpected water activity at larger distances, suggest that the mix of ices inside this nucleus is not a perfect match for typical Solar System examples.

That combination of familiar structure and unusual chemistry is precisely what makes the new ultraviolet image so valuable. It hints that the basic physics of how comets respond to sunlight, shedding gas and dust to form comae and tails, may be universal across planetary systems, while the detailed recipe of ices and organics can vary depending on where and how a comet formed. As more analysis comes in from Europa Clipper’s UVS and other instruments, including the “New ultraviolet image” discussed in a report that notes how New data from the Clipper are being compared with earlier interstellar visitors, I expect scientists to refine their models of where in its home system 3I/ATLAS might have formed and what that implies about the diversity of planetary nurseries in our galaxy.

More from MorningOverview