From the surface, Earth looks like a relatively ordinary rocky planet, wrapped in clouds and a thin blue atmosphere. A new line of research argues that, hundreds of millions of years ago, it may have been framed by a shimmering band of debris, a structure more reminiscent of Saturn than the world we know today. If correct, the idea that Earth once carried a ring of rock and dust does more than reimagine the view from space, it reshapes how I think about ancient climate shifts and the evolution of life.

The emerging picture is that a catastrophic asteroid breakup in the distant past could have filled Earth’s skies with orbiting rubble, altering the pattern of impacts on the surface and even dimming sunlight enough to cool the planet. The claim is bold, but it is grounded in a surprisingly concrete trail of evidence, from fossil meteorites and tiny mineral grains to impact craters and climate records that all seem to point back to the same moment in deep time.

How a ringed Earth entered the scientific conversation

The suggestion that Earth once sported a ring system did not begin as a thought experiment about aesthetics, it grew out of a puzzle in the rock record. Geologists noticed that certain layers from the middle Ordovician period contain an unusual concentration of meteorite fragments and impact signatures, as if the planet had passed through a prolonged storm of space debris. Rather than a single giant collision, the pattern hinted at a sustained shower that demanded a larger, longer lived source.

That mystery led researchers to model what would happen if a large asteroid were torn apart near our planet, with fragments captured into orbit instead of plunging straight to the ground. In the new work, the authors argue that such a breakup could have produced a dense band of material around Earth, a structure that would behave much like a scaled down version of Saturn’s rings. The core of that argument is laid out in a peer reviewed study in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, which frames the ring as a natural outcome of orbital mechanics rather than a speculative flourish.

The Ordovician backdrop and a crowded sky

To understand why this idea matters, I have to start with the setting. During the Ordovician Period, Earth was already a dynamic world, with continents on the move, seas teeming with early animal life, and climate swinging between warm intervals and cooler spells. The proposed ring would have formed in the middle of that chapter, when the biosphere and the planet’s crust were both in flux. According to the new analysis, the key events unfolded some 466 million years ago, a time when the solar system itself may have been rearranging its debris.

The authors describe how, During the Ordovician Period, a time of significant changes for Earth’s life forms, plate tectonics and climate, the planet may have been encircled by a belt of rock that gradually leaked material into the atmosphere and onto the surface. Reporting on the work notes that this scenario could help explain a spike in impacts and a shift toward cooler conditions that appear in the geological record around that same interval, tying the ring hypothesis directly to the broader story of Earth’s Ordovician climate.

The asteroid breakup that seeded a ring

At the heart of the proposal is a violent origin story. The researchers argue that a large parent body in the asteroid belt fragmented, sending a wave of debris inward that intersected Earth’s orbit. Some of that material rained down as meteorites, but a crucial fraction, they suggest, was captured into orbit and spread out into a ring. The study’s Highlights section explicitly notes that Earth may have had a ring during the middle Ordovician, from ca. 466 Ma, and ties that structure to the Breakup of a major asteroid that flooded the inner solar system with fragments.

In their modeling, the team shows how the gravitational interplay between Earth and the incoming rubble could trap a portion of the fragments into a stable band, with the rest continuing on to strike the surface. That scenario is laid out in detail in the Highlights section of the technical paper, which links the timing of the ring to the same 466 M interval recorded in fossil meteorites and impact structures. The key point is that the ring is not an isolated idea, it is the organizing mechanism that makes sense of a whole suite of otherwise disconnected observations.

What the craters and meteorites reveal

The case for a ringed Earth rests heavily on physical scars left behind. When I look at the distribution of known Ordovician impact craters, a pattern emerges: there is a cluster of structures that seem to line up with the predicted paths of debris leaking from a ring rather than arriving randomly from all directions. The new study argues that this alignment is difficult to explain without some kind of orbiting reservoir that fed impacts preferentially into certain latitudes and longitudes over millions of years.

Complementing the craters are fossil meteorites and tiny mineral grains preserved in sedimentary rocks of the same age. These fragments carry chemical fingerprints that point back to a single disrupted parent body, reinforcing the idea of a coordinated bombardment rather than a series of unrelated strikes. Coverage of the work notes that Earth once wore a Saturn like ring, study of ancient craters suggests, and that the distribution of those scars is consistent with a long lived band of debris that slowly decayed, a picture summarized in reporting on ancient impact structures.

How long a ringed Earth might have lasted

One of the most striking claims in the new research is that this was not a fleeting phenomenon. The modeling suggests that once established, the ring could have persisted for tens of millions of years, gradually thinning as particles spiraled inward or were perturbed away. The new study asserts that Earth’s ring formed around 466 m years ago and stuck around for around 40 m years, a span long enough to overlap with major evolutionary and climatic transitions in the Ordovician.

That longevity matters because it gives the ring time to influence both the impact rate and the planet’s energy balance. Over 40 m years, even a modest shading effect from orbiting dust could add up, especially if combined with changes in greenhouse gases and ocean circulation. Reporting on the work emphasizes that scientists used models of how such a ring would evolve to match the observed patterns of craters and meteorites, an approach described in coverage of Earth’s possible long lived ring.

Cooling the planet and reshaping life’s trajectory

If Earth really carried a ring for that long, the implications for climate are profound. A dense band of dust and rock orbiting in the equatorial plane could have blocked a small but significant fraction of incoming sunlight, particularly at certain latitudes. Over geological timescales, that kind of persistent dimming might help tip the climate toward an “icehouse” state, amplifying other cooling trends already underway in the Ordovician oceans and atmosphere.

Some researchers have suggested that such a cooling could be linked to diversification events in marine life, as changing temperatures and sea levels opened new ecological niches. Hundreds of millions of years ago, Earth may have looked quite different when viewed from space, and scientists propose it may have been this ring, combined with shifting continents and carbon cycles, that nudged the planet into a cooler regime, a possibility explored in discussions of how a ring could help create an icehouse period.

Reconstructing the ring with modern tools

Behind the evocative image of a ringed Earth is a very modern toolkit. The research team combined field observations, laboratory analyses, and numerical simulations to test whether a ring could reproduce the patterns they see in the rocks. They mapped the locations and ages of impact craters, cataloged fossil meteorites, and then ran orbital models to see how debris from a single asteroid breakup would behave over tens of millions of years in Earth’s gravitational field.

The effort was led by Andy Tomkins, a researcher at Monash University’s School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, who has spent years studying how extraterrestrial material is preserved in ancient sediments. According to reporting on the project, the researchers, led by Andy Tomkins from Monash University’s School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, published their peer reviewed analysis in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, where they lay out the case that a ring is the simplest way to reconcile the data, a narrative summarized in coverage of whether Earth once had rings.

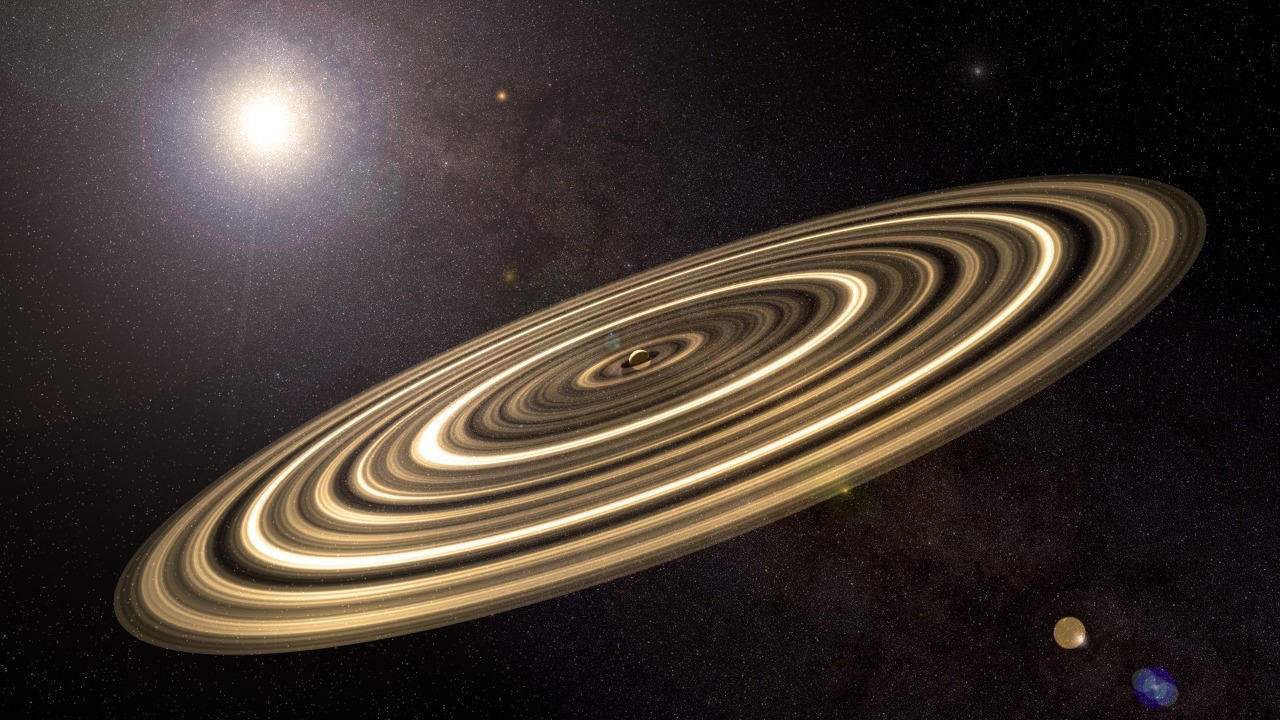

Comparing Earth’s ancient ring to Saturn’s iconic bands

Any mention of planetary rings immediately invites comparison to Saturn, whose bright, icy bands are the showpiece of the outer solar system. The proposed Ordovician ring around Earth would have been far more modest, likely darker and rockier, and confined closer to the planet. Yet the basic physics is similar: countless small particles orbiting in a flattened disk, sculpted by gravity and collisions into a structured system that can persist for millions of years.

In the new work, scientists point out that ring systems are not unique to Saturn, with other gas giants and even smaller bodies showing hints of similar structures. They argue that if a ring can form around a distant planet, there is no fundamental reason Earth could not have briefly joined that club when the conditions were right. Reporting on the study notes that Earth had Saturn like rings 466 million years ago, new study suggests, and places that claim within a broader context of space exploration and solar system dynamics that treats rings as a common, if transient, planetary feature.

Why a ringed Earth matters for today’s science

For me, the most compelling aspect of this hypothesis is not the visual, it is what it reveals about how interconnected planetary processes can be. A single asteroid breakup, filtered through orbital mechanics, could have reshaped Earth’s impact environment, altered its climate, and nudged the trajectory of life, all without leaving any obvious trace in the sky today. That kind of chain reaction is a reminder that deep time is full of feedback loops that only become visible when multiple lines of evidence are stitched together.

The ring idea also sharpens how scientists think about risk and resilience in the present. By studying how an ancient debris belt influenced Earth, researchers gain insight into how future asteroid disruptions or artificial constellations might interact with our atmosphere and surface. The work underscores that Earth is not isolated from the rest of the solar system, it is embedded in a dynamic environment where events far beyond the atmosphere can leave lasting marks on the planet below, a perspective that will continue to shape how I read new findings about Earth’s deep time interactions with space.

More from MorningOverview