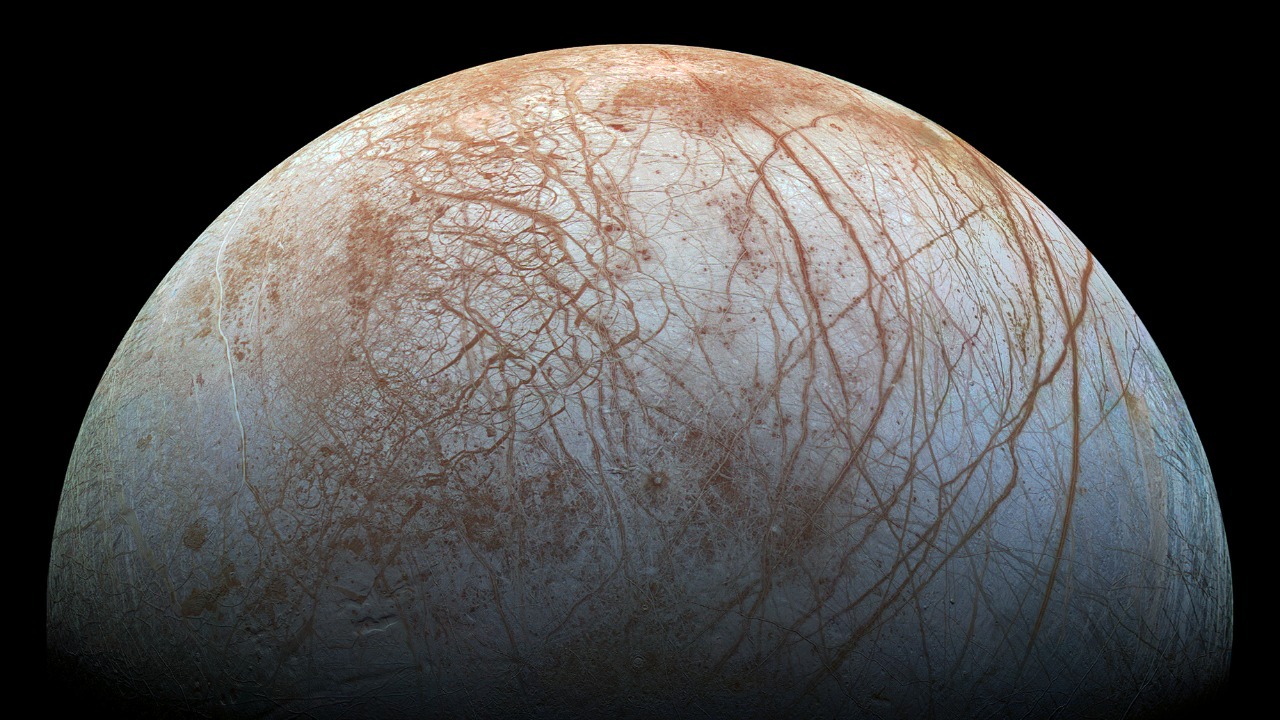

On the cracked ice of Jupiter’s moon Europa, a sprawling pattern of dark lines has taken on an unsettling nickname: a “demon” that looks uncannily like a spider. The feature is not a creature at all, but a frozen scar that is giving planetary scientists one of their clearest clues yet to how water moves beneath Europa’s surface. By tracing the origins of this arachnid-like mark, researchers are edging closer to understanding whether this distant world could support life.

I see the fascination with the “spider” as more than a viral curiosity. It is a test case for how we read alien landscapes, how we separate optical illusion from real geology, and how we prepare for the next wave of close-up exploration that will come with spacecraft like Europa Clipper. The more precisely scientists can decode this eerie pattern, the better they can target the places where Europa’s hidden ocean might be closest to the surface.

The demon-shaped scar that startled Europa-watchers

The feature that has captured so much attention is a sprawling, multi-armed structure etched into Europa’s icy crust, with a central dark patch and radiating lines that resemble legs. When planetary scientists first highlighted it in processed images, the shape immediately invited comparison to a monster silhouette, which is why it picked up the “demon” label and drew parallels to pop culture villains. The resemblance is striking enough that it has been likened to a spider crouched on the ice, its limbs stretching for tens of kilometers across the moon’s surface.

Researchers studying the pattern have focused on how its branching arms intersect with Europa’s existing network of cracks and ridges, suggesting it formed as part of a broader system of surface stress and subsurface flow. The scar sits within a region already known for complex lineations, but its radial symmetry and dark central region set it apart from the more linear fractures that dominate much of Europa’s face, which is why it has become a focal point for new modeling work on how material moves through the ice shell.

Why scientists named it Damhán Alla, the “spider”

To move beyond the informal “demon” nickname, scientists working on the feature have given it a formal label: Damhán Alla, a Gaelic term that means “spider” or “wall demon.” The choice of name captures both the arachnid-like geometry and the unsettling visual impact of the structure, while also tying it to a specific linguistic and cultural tradition. By using the exact phrase Damhán Alla, researchers are signaling that they see this as a coherent, named formation rather than a random tangle of lines on the ice.

The name also reflects how the feature has been framed in public conversation, where it has been compared to the Mind Flayer from a popular science fiction series because of its looming, many-limbed outline. In images of Jupiter’s moon that highlight this region, Damhán Alla appears as a dark, branching blotch that seems to hover over the bright ice, a visual that has helped drive speculation about what kind of process could have carved such a shape as material flowed and froze on Europa, as described in coverage of the bizarre formation.

Europa’s spider is not a creature, but a frozen water trace

Despite the vivid nickname, the consensus among planetary scientists is clear: there are no actual spiders on Jupiter or on Europa. The arachnid comparison is purely visual, a shorthand for the branching pattern that spreads outward from a central point. What matters scientifically is that this pattern appears to be the frozen footprint of activity within Europa’s ice shell, where stresses and moving material have left a permanent mark that can be studied from afar.

Researchers analyzing the spider-like scar argue that it is best understood as a structural feature in the ice, not as a deposit left by falling material or an impact. The way its “legs” intersect with existing cracks suggests that it formed as the surface responded to forces from below, possibly as warmer or saltier material pushed upward and then refroze. That interpretation is central to recent work that frames the scar as a frozen trace of subsurface water movement rather than a surface-only phenomenon, a view supported by detailed discussion of the spider-like scar on Europa.

How salty subsurface water can carve a spider pattern

The leading explanation for Damhán Alla’s shape centers on the behavior of salty water trapped within Europa’s ice shell. Instead of a single, open ocean directly touching the surface, scientists increasingly picture a layered system where pockets and lenses of briny liquid migrate upward, stall, and then freeze. When that happens, the expansion and contraction of ice, combined with the weight of overlying layers, can fracture the surface in radial patterns that resemble spider legs.

In this view, the dark central region of the “demon” marks the place where a plume or pocket of salt-rich water once rose closest to the surface, while the radiating lines trace the stress paths as the surrounding ice adjusted. The idea that the scar may be a frozen trace of salty subsurface water is not just a qualitative guess; it is grounded in detailed interpretations of Europa’s geology that connect the spider-like feature to the broader story of how liquid water once moved here, as highlighted in reporting on how liquid water once moved here.

From “Stranger Things” to serious science

The resemblance between Damhán Alla and a fictional monster has undeniably helped propel it into the public eye, but for the scientists involved, the pop culture comparisons are a gateway to a deeper conversation. When people see a Mind Flayer-like silhouette on a real moon of Jupiter, they are more likely to ask what forces could sculpt such a shape and what that implies about the environment below. I see that curiosity as a useful bridge between entertainment and rigorous planetary science.

Coverage that leans into the “Stranger Things in space” framing has also emphasized that the feature sits on Europa, one of Jupiter’s largest moons and a prime candidate in the search for extraterrestrial life. By tying the eerie visual to the moon’s status as a world with a global subsurface ocean, these stories have helped highlight why a single scar on the ice matters: it may be a visible sign that liquid water, and possibly the chemistry needed for biology, has been active close to the surface in this region, as described in reports that ask what exactly was discovered on Europa.

Simulations that solved a 30‑year Europa mystery

To move from speculation to a concrete origin story for the spider-like demon, researchers have turned to numerical modeling. They have used computer simulation to test how subsurface salty water could produce the observed pattern, varying parameters such as temperature, salinity, and ice thickness to see which combinations yield a radial, multi-armed fracture system. According to reporting on the work, they found that specific configurations of briny water rising and freezing within the ice shell can reproduce the key features of Damhán Alla’s geometry.

These simulations are particularly important because the scar has been puzzling scientists for roughly three decades, ever since high resolution images of Europa first revealed its strange outline. By matching the observed pattern with modeled stress fields and fracture networks, the team has effectively closed a long-standing gap in our understanding of how Europa’s ice responds to internal activity. The description that the researchers used computer simulations to test how subsurface salty water could produce the patterns, and that they found this process could explain the spider-like demon, is laid out in detail in analysis of how they solved the mystery.

Prof. Lauren Mc Keown and the Irish team behind the “spider”

At the center of this effort is Prof. Lauren Mc Keown, a planetary scientist whose work has focused on how icy worlds record the movement of water and other materials in their surfaces. Prof. Lauren Mc Keown and her colleagues have treated Damhán Alla as a natural laboratory, using it to test broader ideas about how fractures propagate in brittle ice when it is stressed from below. Their approach blends image analysis, physical intuition, and the kind of simulation work that can bridge the gap between theory and the specific shapes seen on Europa.

Reporting on the project notes that a team of planetary scientists from Ireland examined and named the large spider-like blob on Europa, framing it with the playful line “Spiders from Mars? Try Europa” to underline how the moon has become a new focus for this kind of research. By carefully mapping the feature and comparing it with other structures on the moon, the group has argued that Damhán Alla is not an isolated oddity but part of a continuum of ice shell behavior that could be common on ocean worlds, a perspective captured in coverage of how Prof. Lauren Mc Keown studied the spider blob.

From Galileo flybys to Europa Clipper’s close‑up view

The data that first revealed Europa’s spider-like demon came from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter and conducted multiple flybys of its moons. Galileo’s images provided the resolution needed to pick out Damhán Alla’s central blotch and radiating arms, but they were limited by the technology and mission design of the time. As a result, scientists have had to squeeze every possible clue from a finite set of pictures, which is part of why the feature remained mysterious for so long.

The next major leap will come from Europa Clipper, a dedicated spacecraft designed to perform dozens of close passes over Europa and map its surface and interior in far greater detail. NASA describes Europa Clipper as a mission that will investigate the moon’s ice shell, subsurface ocean, and potential habitability, with instruments tuned to detect signs of recent or ongoing activity. By targeting regions like Damhán Alla, the mission could directly test whether the spider-like scar sits above a pocket of briny water or a conduit that once connected the ocean to the surface, as outlined in the Europa Clipper mission overview.

What the “spider demon” reveals about Europa’s habitability

For astrobiologists, the most important aspect of Damhán Alla is not its eerie outline but what it implies about the movement of water and salts near the surface. If the spider-like scar is indeed the frozen trace of salty subsurface water, then it points to a dynamic ice shell where material from the deep ocean can be transported upward. That kind of vertical exchange is crucial for any scenario in which Europa’s ocean might support life, because it would help cycle nutrients and energy between the interior and the surface.

The idea that the arachnid-like demon could be linked to processes on the floor of Europa’s subsurface ocean adds another layer of intrigue. Some reporting on the feature notes that scientists are considering how activity at the ocean floor, such as hydrothermal vents, might drive plumes or pockets of warm, salty water that eventually leave marks like Damhán Alla when they interact with the ice above. By tracing the spider’s arms and central region, researchers hope to reconstruct a chain of events that runs from the ocean floor to the visible surface, a connection discussed in detail in analysis of the arachnid-like demon lurking on the gas giant’s moon.

Why “spiders on Jupiter” headlines still matter

Headlines that ask whether there are spiders on Jupiter or on its moons may sound sensational, but they serve a purpose in drawing attention to subtle, technical work on icy geology. When readers click through to find that the “spiders” are actually patterns carved by subsurface water, they are being invited into a more nuanced understanding of how scientists interpret remote images. I see that as a useful trade, where a dramatic hook leads to a deeper appreciation of the methods and constraints of planetary science.

Some coverage explicitly frames the story as a question, asking whether there are spiders on Jupiter and then explaining how, after 30 years, scientists solved the mystery of Europa’s spider demon through careful modeling and image analysis. Other reports emphasize that when you buy through links on their articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission, while still centering the core scientific point that NASA’s Galileo data and follow up work have uncovered the secret origins of the arachnid-like structure lurking on the gas giant’s moon. Together, these narratives show how the same feature can be presented as both a viral curiosity and a serious case study in how spiders on Jupiter became a shorthand for a complex geophysical puzzle.

What comes next for Damhán Alla and Europa’s strange scars

Looking ahead, I expect Damhán Alla to become a prime target for future observations and modeling, especially as Europa Clipper refines our view of the moon’s surface. Higher resolution images, improved topographic maps, and data on the local ice thickness could all test the current hypothesis that the spider-like demon is a frozen trace of salty water. If those measurements line up with the existing simulations, it would strengthen the case that similar features elsewhere on Europa also mark sites of past or present subsurface activity.

At the same time, the methods developed to understand this one scar can be applied to other icy worlds, from Saturn’s moon Enceladus to more distant objects in the outer solar system. The Irish team’s work, led by Prof. Lauren Mc Keown, shows how a combination of careful mapping, physical reasoning, and targeted simulation can turn a visually arresting oddity into a window on deep planetary processes. Whether or not future missions find more “spiders,” the story of Damhán Alla has already expanded our toolkit for reading the cryptic, sometimes unsettling patterns that emerge when alien oceans press against frozen crusts.

More from MorningOverview