Deep in coastal mangroves and even inside our own mouths, biologists are finding that DNA does not always sit in a simple loop at the cell’s center. A giant microbe called Thiovulum imperiosus has now joined a growing cast of organisms that stash their genetic material in unexpected ways, hinting that life has evolved more elaborate strategies for organizing DNA than textbooks long suggested.

By tracing how this oversized bacterium and its microscopic neighbors pack, loop, and sequester their genomes, I can see a pattern emerging: cells keep inventing new tricks to protect DNA, control which genes switch on, and survive in hostile environments. Those tricks, from compartmentalized chromosomes to giant extrachromosomal loops, are quietly rewriting what I thought I knew about the boundary between “simple” microbes and complex cells.

The giant bacterium that breaks the size rules

Thiovulum imperiosus first stands out for its sheer bulk. Typical bacteria measure a few micrometers across, but this species grows so large that individual cells are visible as tiny specks to the naked eye, a scale that immediately raises questions about how it moves nutrients and information around its interior. Biologists have long argued that diffusion limits keep most bacteria small, because molecules must drift passively through the cytoplasm to reach their targets in time.

Because of that reliance on diffusion, researchers have noted that bacteria approaching near millimeter size usually survive only by adopting clever shapes, such as thin filaments or vacuole filled balloons that keep active cytoplasm close to the surface, a principle laid out in work on what determines cell size. Thiovulum imperiosus pushes against those constraints, forcing scientists to ask how a bacterium this big can still coordinate DNA replication, gene expression, and metabolism without the internal transport systems that larger eukaryotic cells use.

A bacterial genome tucked into compartments

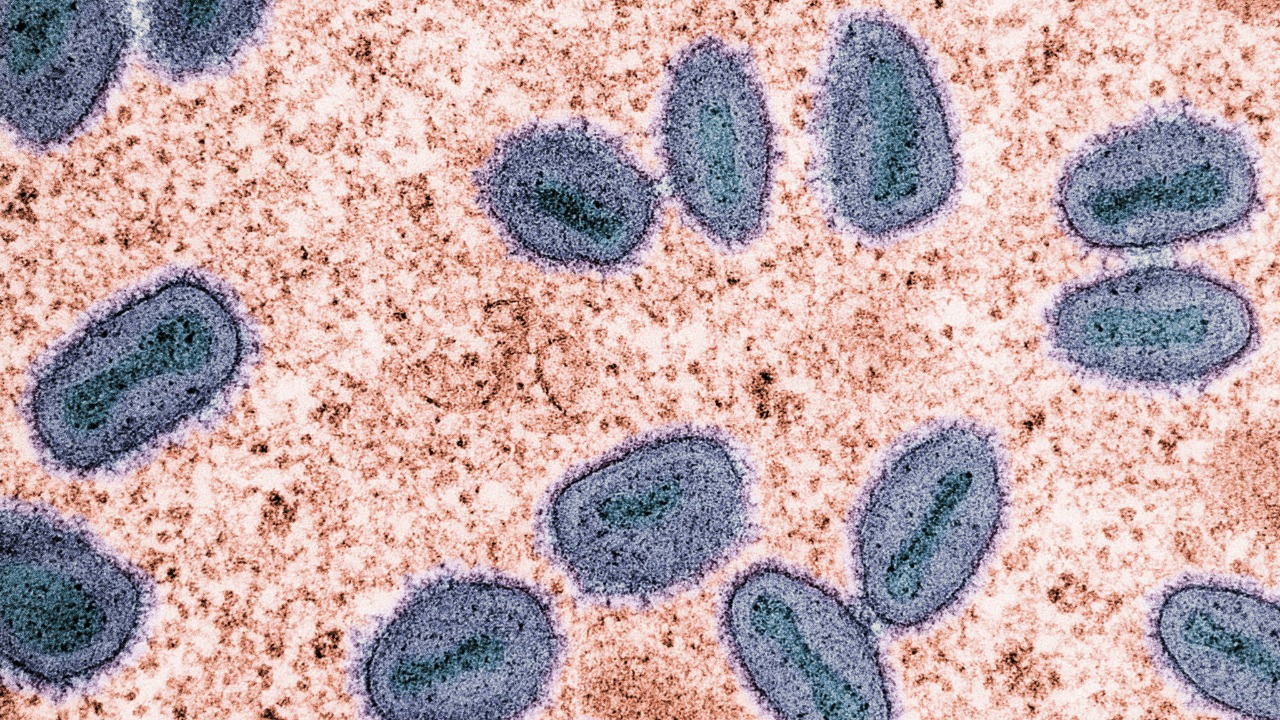

The real shock with Thiovulum imperiosus is not just its size but where it keeps its DNA. Instead of letting its chromosome float freely in a diffuse nucleoid, this giant microbe corrals its genetic material into distinct compartments, a layout that looks more like a primitive nucleus than a typical bacterial interior. That architectural choice suggests the cell is investing energy to separate DNA from the rest of its cytoplasm, potentially to shield it from damage or to fine tune which genes are active in different regions.

Microscopy work on these giant bacteria shows that Thiovulum imperiosus stores its DNA in discrete pockets that resemble membrane bound structures, a pattern that prompted researchers to argue that this kind of compartmentalization may be more common in bacteria than anyone expected, as highlighted in reporting on how this giant microbe organizes its DNA. A related analysis of the same discovery emphasized that the way T. imperiosus compartmentalizes its genome hints that this style of cellular organization could be far more widespread than scientists once suspected, a point underscored in a separate discussion of the bacterium’s unusual DNA layout.

From Thiovulum to the Caribbean giant: a spectrum of bacterial complexity

Thiovulum imperiosus is not the only outsized bacterium forcing a rethink of microbial simplicity. In Caribbean mangroves, researchers identified what they describe as the world’s largest bacterium, a filamentous cell that can reach centimeter scale and still maintain internal order. That organism, like Thiovulum, challenges the old assumption that bacteria are always tiny, structurally simple bags of enzymes and DNA.

Work on the Caribbean species revealed that its genetic material is packaged inside specialized organelle like structures, a feature that led biologist Jean Marie Volland to explain that, until now, researchers thought DNA packaged inside an organelle was solely a hallmark of eukaryotic cells, and that this bacterium has evolved a higher level of complexity, a conclusion captured in coverage of the world’s largest bacterium. Seen alongside Thiovulum imperiosus, this Caribbean giant suggests that bacterial evolution has independently arrived at DNA compartmentalization more than once, hinting at a broader trend toward internal complexity in large prokaryotic cells.

Giant DNA loops hiding in human mouths

While Thiovulum imperiosus and its Caribbean cousin show how bacteria can reorganize chromosomes inside single cells, another surprise has been waiting in human saliva. By carefully analyzing mouth samples, researchers led by Kiguchi uncovered giant loops of DNA that do not sit on the main chromosome at all, but instead exist as separate circles inside oral bacteria. These loops, found in Streptococcus species, add a new layer of genetic architecture to a habitat that already hosts dense microbial communities.

The team, described in a report on giant loops of DNA in our mouths, traced these structures back to Kiguchi et al. in Nat. Commun., which detailed how the loops were discovered through saliva studies and how they might shield bacteria from environmental stress, a story summarized in coverage that highlighted Kiguchi, Nat. Commun., and the unusual DNA loops. A follow up account emphasized that, by exploring this system, researchers identified Inocles, an example of extrachromosomal DNA, describing them as chunks of DNA that exist in cells but are not part of the main chromosome and noting that these structures were found in Streptococcus bacteria, a finding that anchored the term Inocles and the role of extrachromosomal DNA in the oral microbiome.

Inocles and the hidden genome within a genome

The discovery of Inocles reframes how I think about the genetic content of a single bacterial cell. Instead of a lone chromosome, many oral microbes appear to carry an additional layer of information on these giant extrachromosomal elements, which can encode traits that help them cope with the constantly changing environment of the mouth. That means a bacterium’s behavior might shift dramatically depending on whether it carries Inocles, even if its core chromosome looks the same as its neighbors’.

One synthesis of the work on these elements reported that three quarters of all people may host newly identified genetic material called Inocles, and argued that this prevalence could reshape research on gum disease and other oral conditions by revealing how bacteria adapt to the changing environment of the mouth, a point laid out in a summary that stressed that three quarters of people carry Inocles. A more detailed analysis of these elements described Inocles as giant extrachromosomal structures that encode a series of genes contributing to intracellular stress tolerance, including defenses against oxidative stress and DNA damage, and noted that they also influence interactions with oral epithelial cells, a set of functions that underscores how Inocles encoded DNA can act as a hidden genome within a genome.

DNA under siege: how viruses and stress shape genome architecture

These elaborate DNA structures do not evolve in a vacuum. Microbes constantly face threats from viruses, immune defenses, and chemical stress, and their genomes bear the marks of that pressure. When I look at how a mosquito borne virus hijacks human cells, for example, I see another case where genetic material is physically reshaped to survive and replicate in a hostile environment.

In a recent thesis on a mosquito borne virus, researchers described a protein complex that allowed the viral genome to form spherules by acting as a molecular engine, pushing the genome onto cellular membranes and deforming them into characteristic balloon shaped structures, a process that helps the virus replicate while hiding from host defenses, as detailed in work on how this viral genome forms spherules. The same evolutionary arms race likely shapes bacterial strategies: Thiovulum imperiosus may compartmentalize its DNA to protect it from reactive chemicals in mangrove sediments, while Inocles appear to stockpile genes that buffer Streptococcus against oxidative stress and DNA damage in the mouth.

Why size and structure matter for microbial life

Stepping back from individual case studies, a pattern emerges in how size and structure intertwine in microbial evolution. As cells grow larger, whether in Thiovulum imperiosus or the Caribbean giant, they must solve the logistical problem of moving molecules efficiently without the benefit of complex transport systems. DNA organization becomes part of that solution, with genomes tucked into compartments or spread across multiple elements to keep replication and transcription manageable across a bigger volume.

Theoretical work on microbial dimensions has long argued that, because of diffusion constraints, bacteria that approach near millimeter size must adopt specialized morphologies, such as vacuolated interiors that reduce active cytoplasm to a thin shell, a principle spelled out in analyses of how, because of diffusion, only certain shapes allow very large bacteria to function. Thiovulum imperiosus adds a twist by pairing its large size with DNA compartmentalization, suggesting that genome architecture itself can be tuned to help cells operate at scales once thought off limits to prokaryotes.

Redrawing the line between “simple” and “complex” cells

For decades, biology textbooks drew a bright line between prokaryotes and eukaryotes: bacteria and archaea were supposed to have free floating DNA in a simple cytoplasm, while plants, animals, and fungi enjoyed membrane bound nuclei and organelles. Thiovulum imperiosus, the Caribbean giant, and the Inocles rich Streptococcus in our mouths collectively blur that line. They show that bacteria can compartmentalize DNA, package it into organelle like structures, and spin off giant extrachromosomal loops that behave like mini chromosomes.

When Volland pointed out that, until now, scientists thought DNA packaged inside an organelle was solely a feature of eukaryotic cells, and that the Caribbean bacterium has evolved a higher level of complexity, he was implicitly arguing that the old dichotomy no longer holds, a point captured in the description of how, until that discovery, organelle packaged DNA was considered a eukaryotic trait. Thiovulum imperiosus reinforces that message by showing that even bacteria that do not reach centimeter scale can still invest in sophisticated genome organization, hinting that the roots of cellular complexity run deeper and are more widespread across the tree of life than the classic categories suggest.

More from MorningOverview