The James Webb Space Telescope has just confirmed a cosmic fugitive: the first known supermassive black hole racing through intergalactic space at roughly 2.2 million miles per hour, fast enough to cross the distance from Earth to the Moon in less than eight minutes. Instead of quietly anchoring a galaxy, this object is plowing ahead of its former home and leaving behind a spectacular wake of newborn stars that stretches across deep space.

By tracking this runaway giant and the luminous trail in its path, astronomers are watching gravity at its most extreme, catching a rare outcome of a violent galactic encounter that played out billions of years ago. The discovery turns a once theoretical scenario into a vivid, observable phenomenon and opens a new window on how galaxies, and the black holes at their centers, grow and sometimes break apart.

The first confirmed runaway supermassive black hole

For decades, astrophysicists suspected that supermassive black holes could be kicked out of their galaxies, but the evidence was circumstantial and often ambiguous. Now, the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, has delivered what researchers describe as the first decisive case: a supermassive black hole that has been ejected from its host and is now racing through space at about 2.2 million miles per hour, a speed also described as nearly 1,000 kilometers per second in technical reports. That velocity, comparable to 2.2 million mph, is so high that no realistic gravitational tug from the original galaxy can pull the object back.

The black hole has now been given a formal designation, with researchers referring to it as RBH-1, and its detection marks a turning point in how scientists think about the stability of galactic centers. Instead of a static picture in which every large galaxy quietly holds on to its central monster, the new observations show that under the right conditions, even a supermassive black hole can be flung into the cosmic wilderness. That realization forces theorists to revisit long standing models of galaxy evolution and to consider how many other such exiles might be roaming the universe unseen.

A cosmic owl and a light travel time of 7.5 billion years

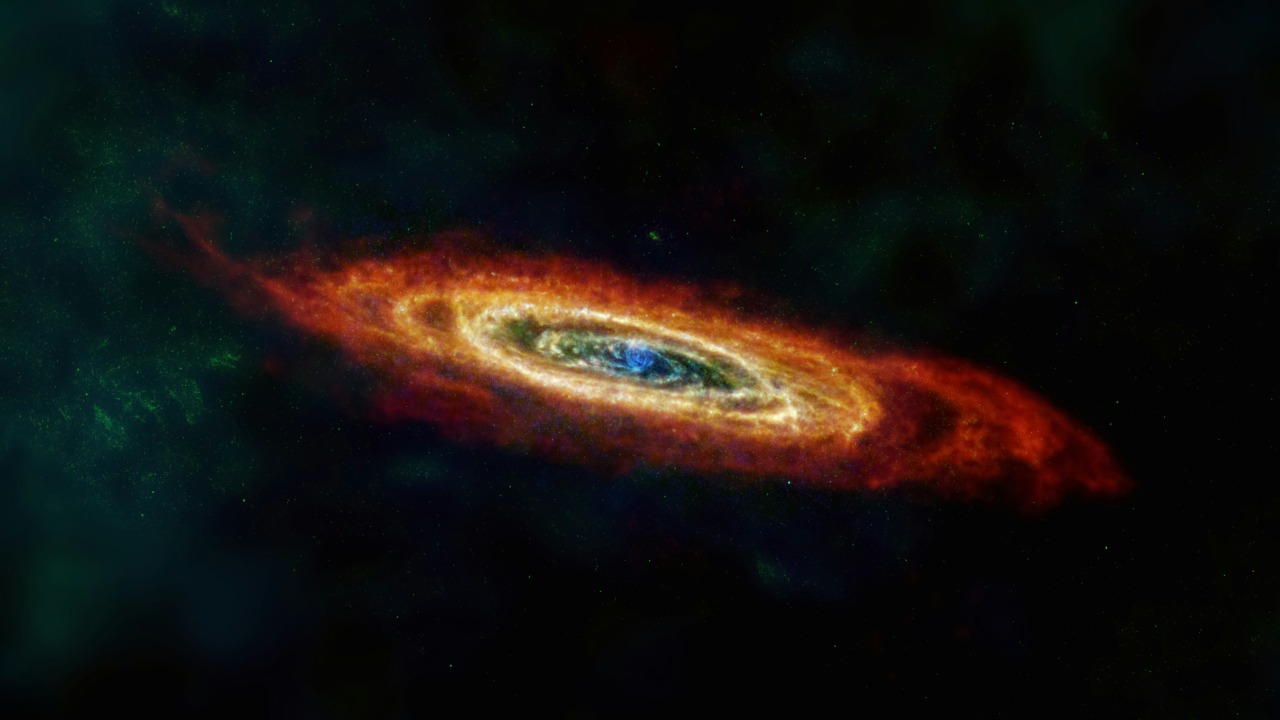

The runaway black hole is not wandering through empty space by chance, it is tied to a striking system informally nicknamed the “Cosmic Owl,” a pair of interacting galaxies whose outline in deep images resembles a bird of prey. The light from this system has taken a staggering 7.5 billion years to reach us, which means RBH-1’s escape played out when the universe was roughly half its current age. By the time the James Webb Space Telescope captured the scene, the black hole had already traveled far from the galactic core, turning the system into a natural time capsule of a long finished drama.

In Webb’s infrared view, the Cosmic Owl’s central region looks oddly quiet for a galaxy that should host a ravenous black hole, while a narrow, bright streak extends outward like a beam from the “eye” of the owl. That mismatch between a seemingly underpowered core and a brilliant linear feature is what first drew astronomers to the target and ultimately led them to identify the streak as the trail of the runaway. Follow up analysis of the structure and its surroundings, supported by detailed imaging of the Cosmic Owl galaxies, confirmed that the luminous line is not a jet or a random filament but the wake of a massive object tearing through intergalactic gas.

How JWST finally nailed the case

Earlier telescopes had hinted that something unusual was happening in this distant system, but they lacked the sensitivity and resolution to separate competing explanations. The James Webb Space Telescope changed that by combining sharp imaging with precise spectroscopy, allowing astronomers to map both the shape of the suspected trail and the motion of the gas and stars within it. With those tools, JWST could show that the bright line is aligned with the direction of motion of a compact, extremely energetic source at its leading edge, consistent with a supermassive black hole that has broken free of its galaxy’s gravity. This decisive view is why several teams now describe the object as the first JWST confirms runaway supermassive black hole.

Crucially, Webb’s spectra reveal that the gas in the trail is not just glowing because it is being shocked, it is also forming stars at a remarkable rate. The instrument’s ability to pick out specific emission lines from hydrogen and other elements shows that the material behind the black hole is cooling and collapsing into new stellar nurseries, rather than simply being heated and dispersed. That combination of a compact, fast moving power source and a star forming wake is difficult to reconcile with alternative scenarios such as a normal galactic jet or a chance alignment of unrelated structures, which is why the case for a true runaway has become so compelling in the wake of the Thank The JWST For Confirming The First Runaway Supermassive Black Hole analysis.

A 200,000 light year trail and a bow shock front

One of the most striking aspects of RBH-1 is the sheer scale of the structure it is carving into space. Astronomers describe Two distinct features: a narrow, star forming tail that stretches roughly 200,000 light years, and a bright, curved front at the leading edge where the black hole’s motion compresses and heats the gas in its path. The tail’s length is comparable to or larger than the diameter of the Milky Way, which underscores how long the black hole has been traveling and how sustained its influence on the surrounding medium has been. The bow shaped front, described as One of the key signatures, marks the point where supersonic motion through intergalactic gas drives a shock that both lights up the region and seeds the wake behind it.

Within this elongated structure, JWST’s data show clumps of gas and dust that are condensing into new stars, effectively turning the black hole’s violent escape into a mobile star factory. The idea that a supermassive black hole, often portrayed as a cosmic destroyer, could instead be triggering star formation along a path hundreds of thousands of light years long is a profound twist on the usual narrative. It suggests that even in extreme events, gravity can play a creative role, sculpting new stellar systems out of the debris of galactic encounters. Visualizations of the system, including an artist’s impression of a runaway supermassive black hole leaving a trail of newborn stars, help convey just how dramatic this process is on cosmic scales.

What could launch a supermassive black hole?

To hurl an object as massive as RBH-1 out of a galaxy requires an extraordinary gravitational slingshot, and the leading explanation involves a complex dance of merging galaxies and their central black holes. When two large galaxies collide, their supermassive black holes sink toward the center of the newly formed system and eventually form a tight binary. If a third galaxy later falls in, bringing its own central black hole, the three body interaction can become unstable, with one of the black holes being flung outward at high speed while the remaining pair recoils in the opposite direction. In the case of the Cosmic Owl, researchers argue that such a multi stage merger is the most plausible way to accelerate a black hole to roughly 2.2 million mph without tearing the entire galaxy apart.

Another possibility, which theorists have long considered, is that asymmetric emission of gravitational waves during the final coalescence of two supermassive black holes could impart a powerful “kick” to the merged remnant. If the gravitational radiation carries away more momentum in one direction than another, the new black hole can recoil in the opposite direction at thousands of kilometers per second. The current observations of RBH-1, including the geometry of the trail and the state of the host galaxy, tend to favor a scenario involving a sequence of galaxy mergers and black hole interactions, as described in analyses of how two galaxies and their central objects can combine to eject a black hole into intergalactic space. Either way, the event would have been among the most energetic and disruptive episodes in the history of the Cosmic Owl system.

RBH-1’s mass and the scale of the disruption

Although the exact mass of RBH-1 is still being refined, early estimates suggest that it is a true supermassive black hole, weighing in at hundreds of millions of times the mass of the Sun. That scale is comparable to or larger than the central black hole in the Milky Way, which means the object carries with it an enormous gravitational sphere of influence. As it plows through intergalactic gas, it drags along a compact accretion disk and possibly a cluster of bound stars, turning the leading edge of the trail into a miniature, high speed galaxy core. The fact that such a massive object could be accelerated to nearly 1,000 kilometers per second without unbinding the entire host galaxy speaks to the precision and violence of the gravitational interactions that launched it, a point underscored in reports that describe the runaway as a Astronomers Spot First example of a runaway black hole speeding through space at 2.2 M miles per hour.

The disruption to the original galaxy is profound but not immediately obvious in a single snapshot. Losing a central black hole of this size can alter the dynamics of the galactic core, change how gas flows toward the center, and reshape the long term star formation history. Over billions of years, the absence of a central gravitational anchor could make the galaxy more vulnerable to tidal stripping by neighbors or to internal instabilities that rearrange its stars. At the same time, the runaway itself is now injecting energy and new stars into regions far from any galactic disk, effectively exporting the consequences of the original merger into the surrounding cosmic web. That dual impact, on both the departed host and the path ahead, is part of what makes RBH-1 such a valuable natural experiment.

Star formation in the wake of a cosmic bullet

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of the discovery is that the black hole’s passage appears to be creating, not just destroying, stellar systems. As RBH-1 barrels through the thin gas between galaxies, its gravity and radiation compress the material into a dense, elongated filament. Within that filament, pockets of gas cool and collapse, igniting new stars that line up behind the black hole like glowing breadcrumbs. Observers describe this as a trail of newborn stars, a phrase that captures how the runaway is effectively painting a luminous line across intergalactic space. The idea that a supermassive black hole could leave behind such a coherent, star forming structure is supported by detailed modeling of the runaway supermassive black hole racing through space at nearly 1,000 km/s and leaving a trail of newborn stars behind.

From a galaxy evolution perspective, this process represents a new channel for distributing stars and heavy elements into the intergalactic medium. Instead of all star formation being confined to galactic disks, some fraction can now occur along the paths of ejected black holes, seeding otherwise empty regions with small, linear collections of stars. Over cosmic time, those structures might disperse or be captured by nearby galaxies, subtly altering their stellar populations. For now, RBH-1 offers a rare, high contrast example of this mechanism in action, giving astronomers a template to search for fainter, older trails that might mark the paths of other, less obvious runaways.

Why this discovery matters for black hole and galaxy theory

RBH-1’s escape from the Cosmic Owl system does more than add a dramatic anecdote to black hole lore, it directly tests long standing theoretical predictions about how galaxies and their central engines evolve. Models of hierarchical structure formation, in which small galaxies merge to form larger ones, have always implied that some fraction of supermassive black holes should be displaced or even ejected during complex interactions. Until now, however, the observational evidence for such events was limited to ambiguous cases where off center bright spots or unusual jets could be explained in multiple ways. With JWST’s confirmation of a clear runaway, theorists can calibrate their simulations against a concrete example, adjusting parameters such as merger rates, black hole masses, and gravitational wave recoil strengths to reproduce the observed 2.2 m mph speed and 200,000 light year trail.

The discovery also has implications for the search for gravitational waves from supermassive black hole mergers, which are being pursued by pulsar timing arrays and future space based observatories. If events like the one that launched RBH-1 are common, they could contribute a distinctive population of high recoil mergers whose gravitational wave signatures differ from those of more sedate, centrally anchored pairs. In addition, the existence of runaway black holes raises questions about how often galaxies are left temporarily or permanently without central engines, which in turn affects feedback processes that regulate star formation. By tying together these threads, the RBH-1 system becomes a bridge between observational astronomy and fundamental physics, linking the detailed structure of a single trail to the broader story of how the universe builds and rearranges its largest objects.

What comes next for RBH-1 and JWST

For astronomers, RBH-1 is less a finished story than a starting point for a new line of inquiry. Follow up observations with JWST and other observatories will aim to refine the black hole’s mass, map the detailed composition of the trail, and search for any residual activity in the core of the Cosmic Owl that might betray the presence of a second, less energetic black hole. Deeper spectroscopy could reveal how the metallicity of the gas changes along the trail, offering clues about whether the material was originally part of the galaxy’s disk or drawn from a more pristine intergalactic reservoir. At the same time, wide field surveys will comb through existing data for similar linear features and off center compact sources, using RBH-1 as a template to identify additional candidates that might have been overlooked.

The James Webb Space Telescope itself is now firmly established as the key instrument for this kind of work, combining the sensitivity to detect faint, distant structures with the resolution to disentangle their internal dynamics. Its success in confirming the first runaway supermassive black hole has already prompted calls to prioritize more observations of interacting galaxies and peculiar linear features, building on the momentum of early reports that urged the community to Share the excitement and dig deeper into the Cosmic Owl system. As the telescope continues to scan the sky, it is likely to find more examples of extreme gravitational events, from additional runaways to exotic mergers, each one adding a new piece to the puzzle of how black holes and galaxies shape the universe together.

More from MorningOverview