For years, Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has been held up as one of the most promising ocean worlds in the solar system, a place where a hidden global sea of liquid water might quietly slosh beneath an icy crust. A new analysis of spacecraft data now challenges that picture, suggesting Titan’s interior could be far more rigid and slushy than oceanic, and that any water may be trapped in pockets rather than pooled in a vast subsurface sea. The shift forces a rethink of how this hazy orange moon formed, how it evolves, and where scientists should look for signs of life inside this icy world.

The emerging view does not strip Titan of its intrigue so much as sharpen it. If the moon lacks a global ocean, then its interior structure, its surface lakes of hydrocarbons, and its potential habitats for biology all need to be reconsidered from the ground up, just as a new generation of missions and telescopes is gearing up to study it in detail.

How Titan became an “ocean world” in the first place

For more than a decade, the consensus in planetary science has been that Titan hides a deep reservoir of liquid water beneath its frozen shell, a belief rooted in gravity and rotation measurements that seemed to show the moon flexing under Saturn’s pull. Those early interpretations painted Titan as a classic ocean world, with a thick ice crust floating atop a global sea, an idea that helped elevate it alongside Europa and Enceladus as a prime target in the search for life inside this icy world, as reflected in reporting on scientists who thought Titan hid a secret ocean. That framework shaped how researchers modeled Titan’s geology, its heat flow, and even the chemistry that might seep up from below to interact with the surface.

Those expectations were reinforced by the broader trend of discovering oceans in unlikely places, from the plumes of Enceladus to the fractured crust of Europa. Titan’s dense atmosphere, rich in organic molecules, made the idea of a buried sea even more compelling, since a subsurface ocean could provide liquid water while the surface offered complex carbon chemistry. In that context, Titan’s supposed ocean became a cornerstone of mission planning and astrobiology roadmaps, guiding everything from telescope campaigns to the design of future landers and orbiters that would probe its interior.

The Cassini legacy and a fresh look at Titan’s tides

The reassessment of Titan’s interior starts with the same spacecraft that built its oceanic reputation in the first place. The Cassini mission spent years orbiting Saturn and repeatedly flying past Titan, collecting exquisitely precise tracking data as the spacecraft was tugged by the gravity of Saturn and Titan. Those measurements, combined with radar and imaging, gave scientists a detailed picture of Titan’s atmosphere and surface and hinted at what lay beneath, a legacy summarized in the Abstract describing how The Cassini mission probed Titan. Yet the same data that once seemed to support a global ocean have now been reanalyzed with new tools, leading to a very different conclusion.

In the new work, researchers focused on how strongly Titan deforms under Saturn’s gravity, a phenomenon known as tidal dissipation. If a thick layer of liquid water sat beneath the ice, the moon should flex more easily, converting orbital energy into internal heat and leaving a clear signature in the spacecraft’s motion. Instead, the updated analysis finds that Titan’s interior resists distortion far more than expected for a world with a vast, low viscosity ocean, a result that points to a stiffer, more solid interior where any water is likely mixed with ice and salts rather than forming a clean, global layer.

A novel analysis that quieted the noise

The turning point in this story is not new hardware but new mathematics. So the study authors, led by JPL postdoctoral researcher Flavio Petricca, revisited Cassini’s tracking data with a sharper eye, applying updated models of Saturn’s gravity and Titan’s motion to tease out subtler signals. Instead of accepting earlier interpretations at face value, they scrutinized the Doppler shifts in the spacecraft’s radio link, the tiny changes in frequency that reveal how Cassini sped up or slowed down as it flew past Titan, a process described in detail in a NASA summary of how So the team used Doppler data. That closer look revealed that some of the apparent flexing could be explained without invoking a global ocean at all.

By applying a novel processing technique, the team reduced the noise in the tracking data and isolated the gravitational fingerprint of Titan’s interior more cleanly. What emerged was a pattern of tidal response that does not match a world with a thick, decoupled ocean layer but instead fits a body whose interior behaves more like a slushy mixture of ice and rock, as highlighted in a description of the technique used by the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). That shift in interpretation does not come from a single dramatic measurement but from a careful reweighing of the evidence, showing how much room there still is to learn from Cassini’s archive.

Titan’s interior: from global ocean to “icy, gooey” slush

The new picture that emerges is of an interior that is cold, viscous, and only partially melted, rather than dominated by a free flowing global sea. Instead of a neat stack of rock, ocean, and ice, Titan may contain a thick, mechanically strong shell with zones of partially melted material, where water and ammonia mix with ice to form a kind of planetary slush. That icy, gooey interior could still host warm pockets of water that behave very differently from a continuous ocean, as described in an analysis of how that icy, gooey interior could shape the search for life on Titan. In this scenario, Titan’s bulk resists Saturn’s tides more strongly, which matches the updated tidal dissipation measurements.

From a geophysical standpoint, a slushy interior changes how heat moves through the moon and how its surface might evolve. Localized pockets of melt could feed cryovolcanic activity or create weak zones where the crust fractures, while large regions remain rigid and cold. The idea that Titan’s interior might be close to its melting point in some layers, yet still behave as a solid overall, helps reconcile the new tidal data with the presence of surface features that hint at internal activity, a balance that is consistent with the constraints laid out in the Nature study on Titan’s strong tidal dissipation. Rather than a single, simple ocean, Titan may be a patchwork of frozen and semi molten zones that evolve over time.

What “no global ocean” really means for habitability

At first glance, the loss of a global ocean might sound like a major downgrade for Titan’s prospects as a habitat for life. A continuous sea of liquid water is an attractive target because it offers a large, stable environment where chemistry can proceed over long timescales. Yet the new interpretation does not eliminate water from Titan’s interior, it simply reshapes where and how that water might exist. That icy, gooey interior could still host warm pockets of water that act as microhabitats, potential sweet spots for life that are smaller but perhaps more dynamic than a single global layer, a possibility emphasized in discussions of how warm pockets of water could be potential sweet spots for life. In that sense, Titan’s habitability may be more fragmented but not necessarily extinguished.

Moreover, Titan’s surface remains a unique laboratory for organic chemistry, with lakes and seas of liquid methane and ethane, a thick nitrogen atmosphere, and a constant drizzle of complex hydrocarbons. Scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory have long argued that even if water is buried deep below the surface, the combination of surface organics and interior heat could still create pathways for interesting chemistry, a view reflected in reporting on how scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory see potential for life on Titan even with water deep below the surface. In that light, the new study narrows the range of possible environments but also sharpens the questions: where exactly are the warmest, wettest niches inside Titan, and how might they communicate with the surface, if at all.

Surprising stiffness: Titan’s resistance to Saturn’s pull

One of the most striking findings in the new work is just how little Titan appears to deform under Saturn’s gravity. Unexpectedly, the scientists discovered that Titan’s interior is resisting distortion from Saturn’s gravitational pull more strongly than a world with a thick, low density ocean should, a result that undercuts the earlier assumption of a global sea and instead points to a more rigid internal structure, as described in coverage noting how Unexpectedly, Titan’s interior resists Saturn’s pull. That resistance shows up in the way Titan’s orbit and rotation respond to tidal forces, leaving a measurable imprint in Cassini’s trajectory.

This stiffness has far reaching implications. A more rigid Titan likely dissipates less tidal energy as heat, which in turn affects how quickly its orbit evolves and how much internal warming it experiences over time. If Titan once had a more extensive ocean that has since frozen or become more viscous, as some researchers suggest, then the moon’s thermal history may include periods of greater internal activity followed by gradual cooling, a narrative that fits with the idea that Titan may once have had more liquid water that later diminished, as noted in the same discussion of Titan’s possible past ocean. That evolutionary arc would make Titan a snapshot of a world in transition rather than a static ocean planet.

Rewriting models of Titan’s formation and evolution

If Titan does not host a global ocean, then many of the models that explain how it formed and cooled will need to be updated. Earlier scenarios often assumed that heat from radioactive decay and tidal flexing kept a deep ocean from freezing entirely, maintaining a liquid layer over billions of years. The new tidal constraints suggest that Titan’s interior may have solidified more extensively, with only localized regions remaining close to the melting point, a conclusion that aligns with the finding that Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean in the Nature analysis of Titan’s interior. That shift will ripple through models of Titan’s early differentiation, its core size, and the composition of its ice shell.

These changes also affect how scientists interpret Titan’s surface features. If the interior is mostly solid, then large scale resurfacing events driven by upwelling ocean material become less likely, while processes like impact gardening, slow tectonics, and atmospheric deposition of organics take center stage. The balance between internal and external forces in shaping Titan’s landscape will need to be recalculated, with particular attention to whether any observed cryovolcanic candidates can still be explained by localized pockets of melt. In that sense, the new study does not just tweak a parameter in existing models, it forces a broader reconsideration of how Titan has evolved from its formation to the present day.

How the new study fits into a broader scientific debate

The claim that Titan may lack a global ocean does not emerge in a vacuum, it sits within a broader debate about how to interpret Cassini’s data and how to weigh different lines of evidence. Earlier analyses of Titan’s gravity field and rotation favored an internal structure with a decoupled shell, while the new work argues that those same observations can be reconciled with a more rigid interior once improved models and processing are applied. Yet, a reanalysis of Cassini data in a new Nature study reveals that Titan likely lacks a vast, global subsurface ocean, a conclusion that directly challenges the long standing ocean world narrative, as summarized in a report noting that Yet, a reanalysis of Cassini data suggests Titan might not have a global ocean. That kind of scientific back and forth is typical when data are pushed to their limits.

In practice, the community will now test the new interpretation against other constraints, from Titan’s moment of inertia to its observed librations, and look for ways to falsify or refine the proposed interior models. Some researchers may argue that hybrid scenarios, with partial oceans or layered structures, still fit the data, while others will embrace the slushy interior as the simplest explanation. The key point is that Cassini’s legacy remains very much alive, with its measurements continuing to yield new insights as analytical techniques improve and as fresh theoretical work explores the range of structures that can match what the spacecraft saw.

What this means for future missions and the search for life

The timing of this reassessment is particularly important because new missions are being designed with Titan’s interior in mind. NASA’s Dragonfly rotorcraft, for example, is planned to explore Titan’s surface and atmosphere, and its science goals have been shaped in part by the expectation of a subsurface ocean that might influence surface chemistry. If Titan’s interior is instead dominated by slushy ice with only localized pockets of liquid, then mission planners may place more emphasis on detecting subtle signs of internal heat, such as temperature anomalies, surface deformation, or unusual compositions in certain regions, rather than expecting broad ocean driven activity. That shift in focus will influence where landers touch down and what instruments they carry.

At the same time, the broader search for life in the outer solar system will need to recalibrate how it ranks potential targets. All in all, ocean worlds remain central to that effort, but Titan’s demotion from the category of worlds with confirmed global oceans to those with more uncertain or localized water changes how it is compared with places like Europa and Enceladus, a point underscored in discussions of how all in all, ocean worlds are still key to the search for life. Titan remains compelling because it combines complex organics with possible interior water, but the pathways that might connect those ingredients are now seen as more intricate and uncertain.

From CAPE CANAVERAL to the public imagination

The new findings have already begun to filter into public awareness, often framed through the lens of launch sites and mission control centers that symbolize space exploration. Reports from CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla describe how Saturn’s moon Titan may not have a buried ocean as long suspected, highlighting that a NASA study suggests Titan may instead have a more rigid interior that resists tidal flexing, as detailed in coverage of how Saturn’s moon Titan may not have a buried ocean as long suspected. Those stories translate a complex geophysical argument into a simple, striking idea: a world once thought to be awash in hidden water might be more frozen and solid than imagined.

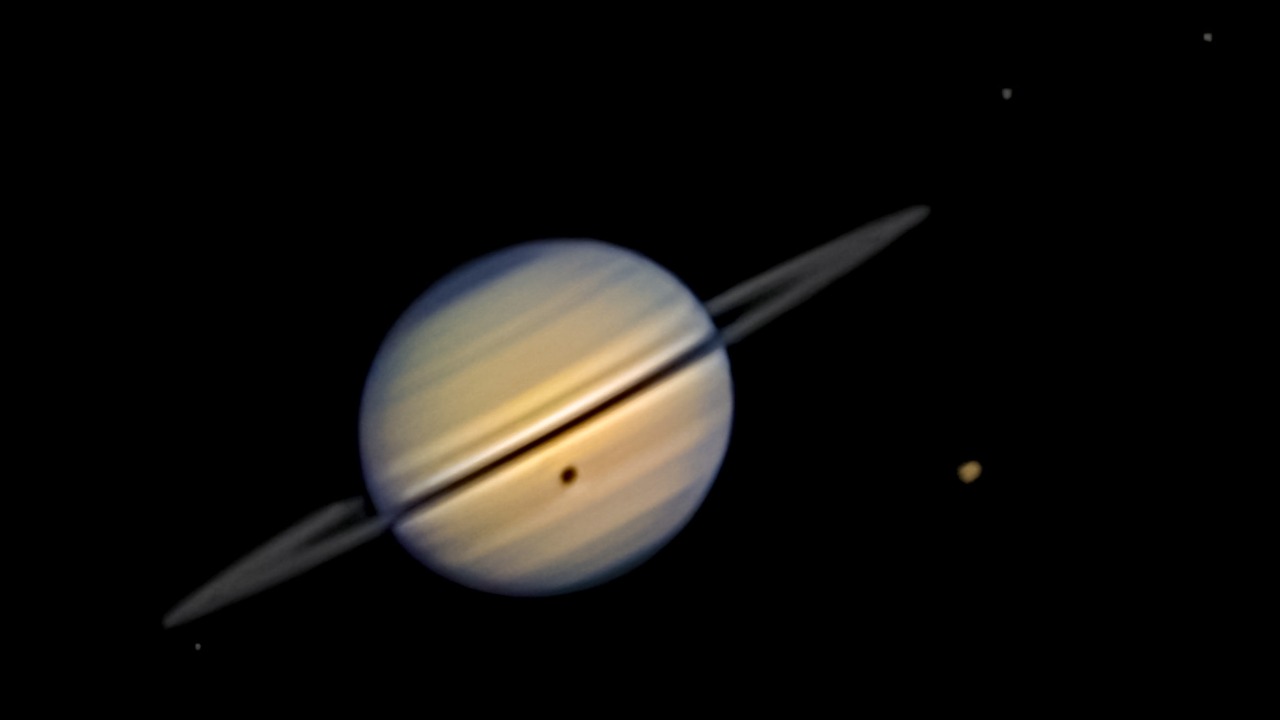

Regional outlets have echoed that message, noting that NASA’s study suggests Titan may not have a global ocean and that scientists will need to probe its interior for signs of life in new ways. One report explains that this image made by the Cassini spacecraft shows Titan as a hazy orb while emphasizing that NASA’s study suggests Titan may lack a global ocean and that future missions will have to look deeper into its interior for signs of life, a narrative captured in a piece noting that NASA’s study suggests Titan may not have a global ocean and that its interior must be probed for signs of life. As those accounts circulate, they reshape how the public imagines Titan, shifting from a hidden ocean world to a more nuanced, layered body whose secrets are still waiting to be uncovered.

More from MorningOverview