The hunt for intelligent life beyond Earth has quietly entered a more exacting phase, and one small, cool star has become a proving ground for how serious that search can be. TRAPPIST-1, a dim red dwarf with seven Earth-sized planets, is now the focus of a coordinated push to catch not just any hint of habitability, but deliberate signals from a technological civilization. The latest campaigns have not heard a whisper, yet they are transforming how I, and many researchers, think about where and how to listen.

Instead of casting a vague net across the sky, scientists are now treating TRAPPIST-1 as a laboratory for precision alien-hunting, from radio technosignatures to atmospheric chemistry. That shift is reshaping the broader search for extraterrestrial intelligence, turning a once speculative quest into a disciplined experiment that can be repeated, refined, and scaled.

Why TRAPPIST-1 became SETI’s favorite test case

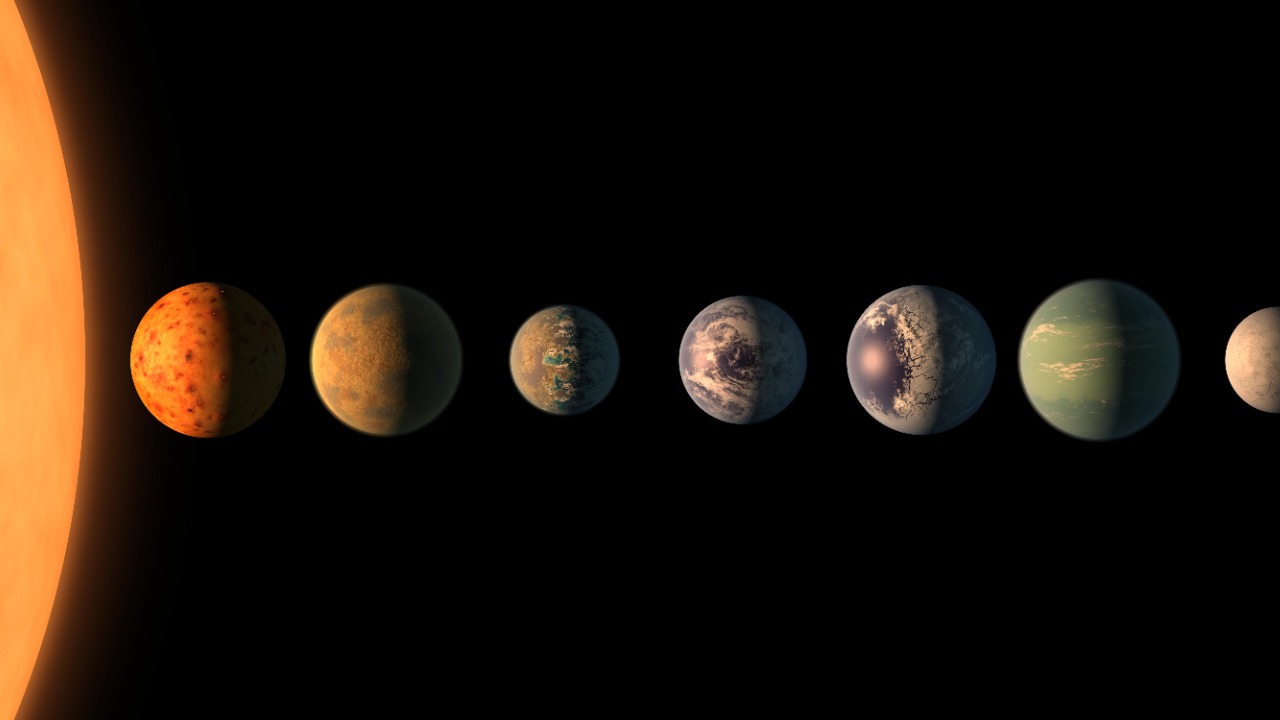

TRAPPIST-1 earned its reputation because it offers something rare in the galaxy: a compact family of seven rocky worlds, several of them in or near the star’s habitable zone, all passing in front of their star from our vantage point. The system orbits a small, cool star about 41 light years away, and that combination of proximity, planetary crowding, and favorable geometry makes it unusually rich territory for both exoplanet science and the search for signals. The TRAPPIST-1 system is exactly the kind of nearby, tightly packed architecture that invites repeated, targeted scrutiny rather than one-off scans.

That is why organizations such as the SETI community have increasingly treated TRAPPIST-1 as a benchmark for how to run modern alien-hunting campaigns. The system’s seven Earth-sized planets let researchers compare worlds under nearly identical stellar conditions, while its transits give instruments a clean way to probe atmospheres and, potentially, detect technosignatures that might ride on top of natural radio noise. In practice, TRAPPIST-1 has become a stress test for every new technique that aims to turn the search for intelligence into a repeatable, data-driven science.

From flaring star to fragile atmospheres

The same qualities that make TRAPPIST-1 attractive also make it harsh. The star is a restless red dwarf that unleashes frequent flares, and that volatile behavior is central to how scientists now judge which of its planets could plausibly host life. Researchers have been modeling the star itself to understand how those eruptions bathe the planets in radiation, and how that radiation might strip away protective gases or, conversely, drive interesting chemistry. In work highlighted by Dec News, scientists are explicitly simulating the flares that were observed in 2022 and 2023 to see whether any of the seven worlds could still be habitable under such conditions, a task that has drawn attention from Dec Scientists and By Samantha Mathewson as part of a broader New wave of TRAPPIST-1 studies.

Those models suggest that the innermost planets may have paid a steep price for their proximity. As a result, the researchers suggested that the innermost TRAPPIST-1 planets may have lost their atmospheres entirely, a sobering conclusion for anyone hoping for lush, close-in oases. That finding, drawn from detailed flare simulations of the TRAPPIST star, reframes the search for life beyond Earth around the outer planets, where radiation is less intense and atmospheres have a better chance of surviving. The idea that the inner worlds might be bare rocks comes directly from work on how TRAPPIST behaves during its most violent outbursts, which is captured in analyses of how the Scientists are modeling the star and how, as a result, the researchers suggested the inner TRAPPIST planets may have lost their atmospheres.

Technosignatures and the new TRAPPIST-1 playbook

While atmospheric models narrow the list of potentially habitable worlds, technosignature hunters are using TRAPPIST-1 to refine how they look for artificial signals. A recent effort described as Researchers Expand Search for Alien Intelligence with New Technosignatures Study of TRAPPIST-1 System shows how teams are moving beyond simple narrowband radio beacons to a broader menu of possible signs of technology. In that work, a group tied to Penn researchers treated the system as a sandbox for testing how to search for engineered emissions that might not resemble the classic “hello” tone that early SETI experiments imagined.

The study, available in preprint on arXiv, treats TRAPPIST-1 as a case where multiple technosignatures could, in principle, overlap: radio transmissions, broadband leakage, or even more exotic engineered phenomena. By designing a campaign that can sift through that complexity, the researchers are effectively writing a new playbook for how to interrogate a promising planetary system. The project, described in detail in a New Technosignatures Study of TRAPPIST System, underscores how TRAPPIST-1 has shifted from a curiosity to a calibration target for the entire field.

What a “null result” at TRAPPIST-1 really tells us

So far, the universe has not rewarded that sophistication with a clear signal. Nick Tusay at the Pennsylvania State University and his colleagues used the system’s geometry to look for radio signals that would be most visible when planets and star line up just right, and they did not find any convincing transmissions. On the surface, that sounds like a disappointment, but the details matter: the team was probing a specific slice of parameter space, at particular frequencies and times, in a system where the odds of a perfectly aligned transmitter are very rare even if someone is out there.

In practice, that silence is a data point, not a verdict. It tells us that within the sensitivity of current instruments, and under the assumptions of that search, there is no obvious beacon shouting from TRAPPIST-1 toward Earth. It does not rule out quieter technologies, different frequencies, or civilizations that are not interested in broadcasting at all. The work by Nick Tusay and colleagues at Pennsylvania State University and others, described in coverage of how search for alien transmissions in this promising star system draws a blank, is better read as a baseline that future, deeper searches will build on.

The Allen Telescope Array’s most detailed TRAPPIST-1 scan yet

One of the most ambitious of those deeper searches has come from the Allen Telescope Array, which has turned its cluster of dishes toward TRAPPIST-1 for a dedicated technosignature campaign. Planetary systems with many tightly packed, low-inclination planets, such as TRAPPIST-1, are predicted to have frequent planetary alignments that can, in theory, make certain signal geometries easier to detect. The latest work uses that insight to time observations so that if any hypothetical transmitters were exploiting those alignments, their signals would stand out more clearly against the background.

The resulting survey has been described as the most sensitive radio technosignature search of TRAPPIST-1 to date, a benchmark that matters because it sets a new floor for what “no signal detected” actually means. By pushing down the noise and covering more of the relevant frequency space, the Allen Telescope Array team has turned TRAPPIST-1 into a reference field for future radio searches of other compact systems. The technical details of how planetary alignments and low inclinations shape this strategy are laid out in a Radio Technosignature Search that treats TRAPPIST as a prototype for similar architectures across the galaxy.

Inside SETI’s evolving toolkit, from pulsar “twinkle” to NVIDIA chips

Behind these targeted campaigns sits a broader transformation in how the SETI Institute and its partners handle data. The organization’s research arm has been tracking how space itself distorts radio signals, using the subtle “twinkle” of pulsars to understand how interstellar plasma smears and scatters transmissions. That work feeds directly into how the Allen Telescope Array calibrates its observations, since any artificial signal from TRAPPIST-1 would have to fight through the same distorting medium as natural sources. By characterizing that distortion, researchers can better distinguish a genuine technosignature from a quirk of the interstellar medium.

At the same time, the SETI Institute is leaning on new hardware to keep up with the firehose of data. In an October roundup, the organization highlighted how the SETI Institute Enhances Extraterrestrial Life Search Using NVIDIA IGX Thor Technology, describing a push to accelerate signal processing and machine learning on the fly. That kind of specialized computing is crucial when scanning complex systems like TRAPPIST-1, where multiple planets, flaring activity, and terrestrial interference all compete for attention. The combination of pulsar “twinkle” studies and advanced processing hardware, detailed in the Institute’s own Research notes and in coverage of how the SETI Institute Enhances Extraterrestrial Life Search Using NVIDIA IGX Thor Technology, is turning TRAPPIST-1 into a proving ground not just for astronomy, but for real-time AI in astrophysics.

TRAPPIST-1e: the mysterious Earth-sized centerpiece

Within the TRAPPIST-1 family, one world has become the star of the habitability conversation. TRAPPIST-1e, an Earth-sized planet in the system’s habitable zone, is drawing scientific attention as researchers hunt for signs of a stable atmosphere and potentially life-friendly conditions. Its size and orbit make it the closest analog to our own planet in the system, and that has put it at the center of observing campaigns with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which can dissect starlight that filters through any gases around the planet.

Those observations have already complicated the story. Last September, astronomers published two papers that said the Earth-sized TRAPPIST-1e might host a methane-rich atmosphere, a tantalizing possibility because methane can be produced by both geological and biological processes. More recent work has questioned that interpretation, arguing that the data can be explained without invoking a thick methane blanket, and that there could still be a thinner or more complex mix of gases. The debate, captured in reporting on how researchers question methane atmosphere on TRAPPIST-1e and how a nearby Earth-size planet just got much more mysterious, shows how quickly our picture of this Earth analog is evolving as new Webb data arrive.

Testing a new alien-hunting strategy on a silent system

Even as atmospheric studies of TRAPPIST-1e unfold, SETI teams have been using the entire system to trial a new observing strategy. The latest hunt for alien signals in the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system has test-driven an approach that treats each planet’s orbit as an opportunity to catch time-dependent signals, rather than assuming a constant beacon. By watching during key orbital phases, such as when a planet passes behind or in front of the star, researchers can search for patterns that might indicate directed transmissions or engineered reflections.

In practice, this means building schedules around planetary ephemerides and coordinating radio observations with optical and infrared campaigns, so that any oddities can be cross-checked across wavelengths. The early verdict is that the TRAPPIST-1 planets remain silent within the sensitivity of current instruments, but the strategy itself has proved its worth as a template for future searches. The approach is described in coverage of how SETI tests new alien-hunting strategy, which frames TRAPPIST as a rehearsal for more ambitious, multi-planet campaigns elsewhere.

Students, the Allen Telescope Array, and the next generation of TRAPPIST-1 listeners

One of the quieter revolutions around TRAPPIST-1 is educational. The Allen Telescope Array has not only been a workhorse for professional technosignature searches, it has also become a classroom for training the next wave of signal hunters. In a recent project, scientists used the array to search for radio signals in the TRAPPIST-1 star system while involving students directly in data collection and analysis. Participants described it as an exciting way to involve students in cutting-edge SETI research, turning abstract questions about alien life into hands-on experience with real telescopes and real noise.

That kind of engagement matters because the search for intelligence is, by design, a long game that will outlast any single observing run or instrument. By giving students a stake in systems like TRAPPIST-1, researchers are seeding the field with people who understand both the technical challenges and the philosophical stakes of listening for other minds. The educational dimension of the Allen Telescope Array’s work, and the description of how it was an exciting way to involve students in cutting-edge SETI research in The TRAPPIST-1 system, is captured in the account of how Scientists Use Allen Telescope Array to search for radio signals in the TRAPPIST-1 star system.

Why a quiet TRAPPIST-1 still matters for the search

For now, TRAPPIST-1 is a paradoxical kind of success story. The system has yielded no confirmed alien signals, and its innermost planets may be stripped of atmospheres, yet it has become central to how scientists refine their tools, test their assumptions, and train new observers. Each null result tightens the constraints on what kinds of civilizations could be present and undetected, while each new atmospheric spectrum from TRAPPIST-1e or its siblings sharpens our sense of what a habitable world looks like around a flaring red dwarf.

In that sense, the search for alien signals in TRAPPIST-1 has indeed “got real,” not because it has delivered a dramatic discovery, but because it has forced the field to behave like any other branch of precision astronomy. The work now involves carefully modeled stars, quantified detection limits, advanced hardware, and a willingness to let data overturn early hopes, whether about methane on TRAPPIST-1e or about easy-to-spot radio beacons. Whatever future systems take center stage, the methods being forged around this small, cool star about 41 light years away will shape how we listen for company in the galaxy for years to come.

More from MorningOverview