Far from our solar system, astronomers have spotted a world that looks less like a sphere and more like a squeezed lemon, a distorted gas giant that refuses to behave the way planetary theory says it should. The object, PSR J2322-2650b, is forcing researchers to rethink how planets form, survive and evolve in some of the harshest environments the universe can offer.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, scientists have begun to peel back the layers of this strange planet’s atmosphere and interior, only to find a puzzle that deepens with every new observation. Instead of neatly fitting into known categories, this lemon-shaped outlier is scrambling the rulebook on everything from tidal forces to exotic chemistry.

Meet PSR J2322-2650b, the lemon-shaped world

The planet at the center of this mystery is PSR J2322-2650b, a gas giant with roughly the mass of Jupiter that has been stretched into an oblong, lemon-like shape by extreme gravitational forces. Rather than orbiting a familiar type of star, it circles a compact stellar remnant known as a pulsar, which batters the planet with intense radiation and gravity. In the initial reports, the planet is described as a Jupiter-mass object whose bulk has been pulled into a distorted profile that is unlike the nearly spherical silhouettes seen in most other exoplanets.

Researchers have dubbed this object PSR J2322-2650b, emphasizing both its planetary status and its tight link to the pulsar that dominates its environment, and they describe it as a Jupiter-mass gas giant that has been reshaped by its host star’s pull into a configuration that looks more like a lemon than a ball. That basic description, including the name and mass of the planet, is laid out in coverage that notes how the system’s pulsar host and the planet’s unusual geometry set it apart from more conventional hot Jupiters and other gas giants dubbed PSR.

A planet in the grip of a pulsar

To understand why PSR J2322-2650b looks so strange, it helps to look at its host. The planet orbits a pulsar, a rapidly spinning neutron star that packs more mass than the Sun into a city-sized sphere and sweeps beams of radiation across space like a lighthouse. These objects are the remnants of massive stars that exploded as supernovas, leaving behind cores so dense that a teaspoon of their material would outweigh a mountain. In this system, the pulsar’s gravity and radiation dominate everything, from the planet’s orbit to its shape.

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have focused on how this pulsar environment sculpts the planet, noting that the host is a rapidly spinning neutron star whose beams of energy flash past the planet as it orbits. The same reporting that highlights the planet’s lemon-like profile also explains that the pulsar’s lighthouse-style beams and compact mass are central to the system’s dynamics, with the neutron star’s spin and radiation pattern shaping both the observational signatures and the physical stress on the planet as a lighthouse.

How Webb saw a lemon instead of a sphere

The James Webb Space Telescope was designed to pick up faint heat signatures and subtle spectral fingerprints, and those capabilities are exactly what allowed scientists to recognize that PSR J2322-2650b is not a simple sphere. By tracking how the planet’s light changes as it moves around the pulsar and passes behind it, researchers can reconstruct its silhouette and temperature distribution. In this case, the data show a world that is stretched along the line connecting it to the pulsar, a telltale sign that gravity is pulling harder on the side facing the star than on the far side.

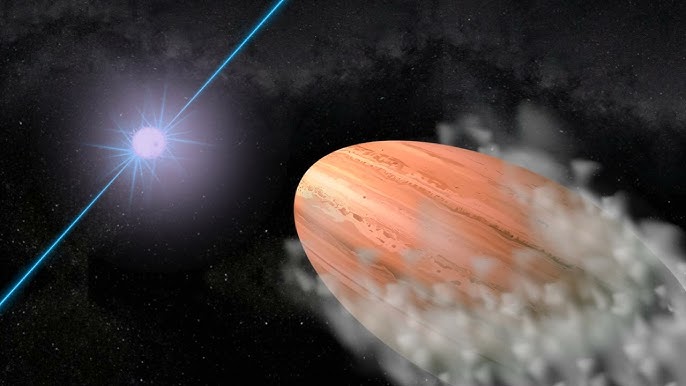

According to NASA, Webb’s instruments have captured the planet and its host in detail, including an artist’s concept that visualizes the exoplanet PSR J2322-2650b and the pulsar as a distorted, tidally stressed pair. The description of this system emphasizes that gravitational forces from the much heavier pulsar are pulling the planet into an elongated shape, and that the planet whips around its host in just 7.8 hours, a configuration that naturally leads to a lemon-like profile rather than a neat sphere gravitational forces from the much heavier pulsar.

Why the shape shocks planet-formation theory

At first glance, a distorted planet might not sound revolutionary, since tidal forces can stretch worlds that orbit very close to their stars. But PSR J2322-2650b is not simply another hot Jupiter grazing a main sequence star. It is a survivor in a system that has already gone through a supernova, leaving behind a neutron star that should have stripped or destroyed nearby planets. The fact that a Jupiter-mass world not only persists but has been reshaped into a lemon-like form suggests that standard models of how planets form and endure around such extreme objects are incomplete.

Reporting on this discovery stresses that the planet’s combination of carbon-rich atmosphere, extraordinarily high temperatures and distorted geometry makes it unlike any other known world, and that its existence appears to defy the usual rules of planet formation. The same coverage notes that this distant world’s chemistry and structure do not fit neatly into existing categories, and that its carbon seems more inclined to bond with other atoms than to itself, a clue that the processes that built and reshaped it may be very different from those that operate in more familiar planetary systems defies the rules of planet formation.

Diamonds in the dark: what might be inside

One of the most attention-grabbing ideas about PSR J2322-2650b is that its interior may be packed with diamond. Under the immense pressures expected inside a carbon-rich, Jupiter-mass planet, carbon atoms can be squeezed into crystalline structures, potentially turning large portions of the mantle or core into solid diamond. Combined with the planet’s distorted shape, that possibility has led some scientists to describe it as a kind of cosmic jewel, a world whose internal structure is as exotic as its outline.

A video and accompanying description from the Space Telescope Science Institute highlight this angle, describing a bizarre, lemon-shaped planet that may contain diamonds at its core and that is challenging long-standing ideas about how planets form. The same material frames the object as a test case for theories of high-pressure carbon chemistry and planetary interiors, suggesting that the combination of extreme gravity, rapid orbit and unusual composition could produce layers of diamond deep beneath the visible atmosphere may contain diamonds at its core.

From WASP-103 b to PSR J2322-2650b: a new class of stretched worlds

PSR J2322-2650b is not the first exoplanet known to be distorted by tides, but it is pushing that phenomenon into a new regime. Earlier work on planets like WASP-103 b, a hot Jupiter that orbits extremely close to its star, showed that strong tidal forces can puff up and slightly stretch a gas giant. Those observations hinted that some exoplanets might deviate from perfect spheres, but the effect was modest compared with what is now being inferred for the pulsar planet. In the case of PSR J2322-2650b, the host is not a normal star but a neutron star, and the resulting gravitational field is far more intense.

NASA’s catalog entry for WASP-103 b describes it as a gas giant that is already being pulled into an oblate, tidally distorted shape by its proximity to its star, providing an earlier example of how gravity can reshape a planet’s bulk. By setting that case alongside the new pulsar planet, researchers can begin to sketch out a spectrum of stretched worlds, from hot Jupiters around ordinary stars to lemon-shaped giants in the grip of compact remnants, and use those comparisons to refine models of how gas giants respond to extreme tidal stress WASP-103 b.

The University of Chicago team behind the discovery

Behind the dramatic images and artist’s concepts is a group of researchers who have spent years preparing to use Webb on such extreme systems. The work on PSR J2322-2650b is led by scientists who specialize in exoplanet atmospheres and compact objects, and who saw in this pulsar system a rare chance to test theories about how planets behave under crushing gravity and intense radiation. Their analysis combines Webb’s infrared data with radio observations of the pulsar, stitching together a picture of a world that is both familiar in mass and utterly alien in context.

The University of Chicago’s Michael Zhang, identified as the principal study investigator, has emphasized that the planet orbits a star that is completely unlike the Sun and that the system’s configuration raises basic questions about how such a world could have formed and survived. Coverage of the discovery notes that Zhang and his colleagues are using Webb’s measurements to probe the planet’s atmosphere and shape, and that their work is part of a broader effort to understand how planets can exist in environments dominated by compact remnants and extreme gravity The University of Chicago’s Michael Zhang.

What Webb is revealing about the atmosphere

Shape is only part of the story. Webb’s infrared instruments are also dissecting the planet’s atmosphere, revealing a mix of elements and molecules that does not line up neatly with expectations. Early analyses suggest that the atmosphere contains carbon in forms that challenge standard models, with hints that the balance between carbon and other atoms is skewed in ways that could influence cloud formation, heat transport and even the planet’s long-term evolution. For a gas giant under such intense tidal stress, the atmosphere may be both a shield and a conduit, redistributing energy while slowly bleeding material into space.

Scientists using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have described this as an entirely new type of exoplanet whose atmospheric composition defies easy explanation, noting that the faraway planet’s chemistry and structure appear to be shaped by its close orbit around a rapidly spinning neutron star. The same reporting underscores that the combination of a bizarre atmosphere and a lemon-like geometry makes PSR J2322-2650b a key test case for understanding how extreme radiation and gravity can sculpt both the bulk and the gaseous envelope of a planet bizarre atmosphere.

Why scientists are genuinely baffled

For all the excitement, the dominant mood among researchers is puzzlement. PSR J2322-2650b sits at the intersection of several fields, from exoplanet science to pulsar astrophysics, and it refuses to behave in a way that any single model can fully explain. Its mass is similar to Jupiter’s, yet its shape is far more distorted than typical hot Jupiters. Its host is a pulsar that should have blasted away nearby material, yet a massive planet remains in a tight orbit. Its atmosphere shows signs of unusual chemistry, and its interior may be dense with diamond. Each of those facts is surprising on its own; together, they amount to a direct challenge to existing theories.

Astronomers who have studied the system with the James Webb Space Telescope have been explicit that the planet defies explanation, describing it as a bizarre-looking exoplanet that does not fit into known categories and that forces them to revisit assumptions about how planets form and evolve around compact objects. Their accounts emphasize that the combination of a lemon-like shape, a pulsar host and exotic atmospheric signatures makes PSR J2322-2650b one of the most perplexing worlds yet identified, a case where the data are clear but the theoretical framework is still catching up astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope.

A legacy of weird pulsar planets

Part of what makes PSR J2322-2650b so intriguing is that it joins a small but growing family of planets around pulsars, a class of objects that has been surprising astronomers for decades. The very first confirmed exoplanets were not found around a Sun-like star but around a pulsar, in a system where the planets were named Poltergeist and Phobetor. Those early discoveries showed that planets could exist in the aftermath of a supernova, either as survivors of the original system or as second-generation worlds built from the debris. PSR J2322-2650b now extends that story by adding a dramatically distorted gas giant to the mix.

Accounts of pulsar planets recall that the first worlds beyond the solar system ever confirmed were Poltergeist, also known as PSR B1257+12 B, and Phobetor, also known as PSR B1257+12 C, which orbit a pulsar and demonstrated that planetary systems can arise in environments once thought too hostile. The same reporting that revisits those early discoveries now sets them alongside the new lemon-shaped planet, suggesting that PSR J2322-2650b may represent a further step in understanding how pulsar systems can host a surprising diversity of planetary companions Poltergeist and Phobetor.

Webb, NASA and international partners push the frontier

The discovery and characterization of PSR J2322-2650b are also a showcase for the James Webb Space Telescope itself and for the international collaboration that built and operates it. NASA, working with the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, designed Webb to probe the earliest galaxies, the birthplaces of stars and the atmospheres of exoplanets. In this case, those capabilities are being applied to a system that sits at the edge of what planetary science can currently explain, turning a telescope built for cosmology and galaxy evolution into a tool for dissecting a single, very strange world.

Coverage of the lemon-like planet notes that NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope captured PSR J2322-2650b in partnership with ESA and CSA, and that the resulting data are being used to explore what the planet is made of and how it ended up in its current state. The same reports emphasize that the system’s true nature remains a mystery, underscoring how even a flagship observatory with cutting-edge instruments can encounter objects that resist easy interpretation and that will require years of follow-up work to fully understand NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

How the findings are being shared and scrutinized

As with any major astronomical discovery, the story of PSR J2322-2650b is unfolding not just in observatories and data archives but also in journals, conferences and public-facing reports. Researchers have submitted their analysis to peer-reviewed outlets, where other scientists can test the methods and challenge the interpretations. At the same time, the basic facts of the discovery are being communicated to a wider audience through news stories, institutional releases and visualizations that translate complex physics into accessible narratives.

Reports on the lemon-like planet explain that researchers have published a paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, detailing how the planet appears to have an exotic composition and a distorted shape that push against existing models. Those accounts also note that the team’s findings are being discussed in broader national coverage, which highlights both the technical achievement of measuring such a strange world and the open questions that remain about its origin and fate Researchers, who have published a paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

What this lemon-shaped planet means for the future of exoplanet science

For planetary scientists, PSR J2322-2650b is less an oddity to be filed away and more a signpost pointing toward a richer, stranger universe of worlds. Each time telescopes like Webb uncover a planet that breaks the rules, theorists are forced to refine their models, adding new physics or new pathways for planet formation and evolution. In the case of this lemon-shaped gas giant, the implications touch on everything from how gas giants respond to extreme tides to how planetary systems can rebuild themselves after a supernova. It suggests that the census of exoplanets is still heavily biased toward the easy-to-find and easy-to-explain, and that many more outliers are likely waiting in the data.

Some accounts of the discovery frame it as part of a broader pattern in which strange, tidally distorted and compositionally exotic planets are becoming more visible as instruments improve, and they point out that PSR J2322-2650b may be only the first of several such worlds that Webb will uncover around compact objects. One detailed discussion of the system notes that at just around 1 million years after the supernova that created the pulsar, the environment would have been extraordinarily hostile, yet a planet managed either to survive or to form from the debris, a scenario that challenges simple narratives about planetary destruction and rebirth at just around 1 million.

More from MorningOverview