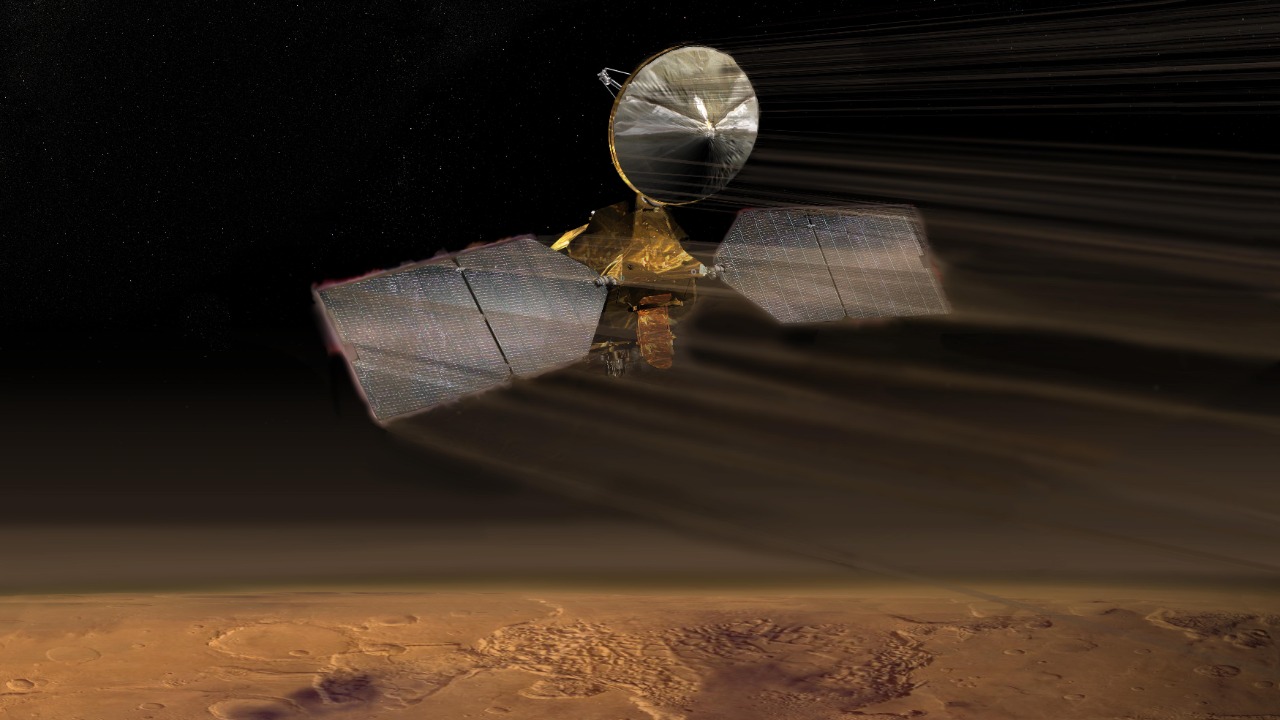

The spacecraft that has quietly rewritten our understanding of Mars just crossed a very visible milestone: the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has captured its 100,000th close-up view of the Red Planet. That single image is more than a round number, it is a marker of how a long-lived mission has turned Mars from a distant disk into a mapped and monitored world.

From orbit, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has watched dust storms bloom, ice caps shift, and rover tracks snake across ancient terrain, building a visual archive that now spans hundreds of terabits of data. Its latest benchmark, driven by the HiRISE camera, underlines how a platform launched to scout landing sites has become the reference atlas for any future human visitors.

MRO’s long road to a six-figure milestone

When NASA sent Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter toward Mars, the spacecraft was designed as a workhorse rather than a headline grabber, a platform meant to circle the Red Planet for a few years and beam back detailed data. Instead, it has evolved into a fixture of Martian exploration, operating far beyond its original expectations and now celebrating the 100,000th image from its premier camera. The orbiter went into service above the Red Planet in November 2006, and over nearly two decades it has shifted from a newcomer in Martian orbit to the senior scout that every new mission relies on for context and communication.

That longevity has translated into a staggering scientific return. As of July, the MRO had already returned over 450 terabits of data, a figure that dwarfs the output of many earlier deep space missions and reflects how central it has become to Mars science. The 100,000-image mark for its high-resolution camera is nested inside that broader torrent of information, a reminder that each crisp frame is part of a much larger, methodical survey of the planet’s surface and atmosphere.

HiRISE: the eye that made Mars feel close

The milestone belongs in large part to HiRISE, the high-resolution camera that has turned Mars from a blurry globe into a place where individual boulders, dune ripples, and rover hardware are visible. I see HiRISE as the instrument that made Mars feel less like an abstract destination and more like a landscape people can imagine walking across, because its images routinely resolve features on the scale of city streets. That intimacy is why the 100,000th image resonates, it is another entry in a catalog that has already shown cliffs, avalanches, and layered ice in extraordinary detail.

Engineers and scientists have long treated HiRISE as one of NASA’s key cameras orbiting Mars, and the 100,000-image threshold underscores that status. The instrument does more than take pretty pictures, its stereo pairs help generate elevation models, its color filters tease out subtle mineral differences, and its repeat imaging lets researchers track seasonal changes. Each new frame, including the latest one, feeds into that layered understanding of how the Martian surface is shaped and reshaped over time.

What the 100,000th image actually shows

Milestones can be symbolic, but in this case the image itself is scientifically rich. The 100,000th HiRISE view highlights mesas and dunes, a combination that captures both the erosional history of Mars and the active processes still at work on its surface. Mesas and other flat-topped landforms often preserve older rock layers, while dunes trace the current behavior of the thin Martian atmosphere as it pushes sand into organized waves. Seeing both in a single frame is a reminder that Mars is not geologically dead, it is a planet where ancient landscapes and modern winds intersect.

In the shared view, mesas and dune fields stand out with striking clarity, their shapes and shadows picked out by the camera’s sharp optics and careful image processing. The composition, highlighted in a social media post that celebrated how Mesas and dunes dominate the scene, is not just visually compelling, it is also a practical dataset for scientists modeling wind patterns and erosion rates. The fact that this kind of detailed, layered terrain can now be captured as the 100,000th entry in a long-running series shows how routine high-end planetary imaging has become for the mission.

From scouting landing sites to guiding future explorers

When I look back at the arc of Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the most striking shift is how it moved from a mission focused on reconnaissance for robotic landers to a foundational tool for planning eventual human exploration. Early in its life, the spacecraft’s detailed maps were used to choose safe landing sites for NASA’s Mars landers, identifying flat, rock-poor zones where parachutes and retro-rockets would have the best chance of delivering hardware intact. That role has only grown as more complex missions, from rovers to sample return hardware, have demanded precise knowledge of slopes, boulder fields, and dust cover.

Those same capabilities now feed directly into discussions about where the first human visitors might set foot. High-resolution images and elevation data help mission planners weigh trade-offs between scientific interest, resource availability, and landing safety, turning abstract regions into well-characterized neighborhoods. Reporting on the mission has emphasized how NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is already being used to think through the needs of the first human visitors, from access to water ice to terrain that can support habitats and power systems. The 100,000th image is part of that same scouting effort, another tile in the mosaic that future crews will rely on.

A camera that does more than count to 100,000

It is tempting to treat the 100,000th image as a finish line, but the real story is how HiRISE and its host spacecraft have built a continuous, evolving record of Martian change. Over time, repeated passes over the same regions have captured fresh impact craters, shifting dunes, and frost patterns that advance and retreat with the seasons. That time-lapse view is only possible because the camera has been kept active and productive long enough to accumulate such a large image count, turning what might have been a static atlas into a dynamic chronicle.

The mission team has leaned into that continuity, using HiRISE to monitor sites where landers and rovers operate, track dust storm development, and follow the behavior of polar ice. The 100,000-image mark reflects a strategy in which the camera is treated as a long-term observer, not a one-off survey instrument. Official updates have framed the milestone as a moment to Watch highlights from a vast archive, but the more important point is that the archive is still growing, with each new orbit adding fresh context to what came before.

How the milestone fits into Mars science

In scientific terms, the value of 100,000 high-resolution images lies in coverage and correlation. With so many targeted observations, researchers can link small-scale features to broader regional patterns, connecting a single gully or landslide to the climate and geology of an entire basin. That is crucial for questions about water, ice, and habitability, where local details often hold the key to interpreting global models. The milestone image, focused on mesas and dunes, is one more data point in ongoing efforts to understand how sediment moves and accumulates on Mars, and what that movement says about wind strength and atmospheric density.

The broader Mars community has treated the achievement as a chance to revisit how much of the planet has been imaged at this level of detail and where gaps remain. Coverage maps built from HiRISE data show dense clusters over landing sites and scientifically rich regions, with sparser sampling elsewhere, a pattern that reflects the need to balance fuel, data volume, and scientific priorities. Commentary around the milestone has highlighted how the camera’s 100,000th frame fits into a wide-ranging mission that spans everything from polar ice studies to the search for ancient river deltas. In that sense, the new image is less a standalone highlight and more a representative slice of a very large, carefully curated dataset.

Public fascination and the power of shared images

Beyond the science, the 100,000th image underscores how central public engagement has become to planetary missions. HiRISE images are not just archived in technical databases, they are routinely shared on social platforms and in online galleries where people can zoom in on dunes, craters, and rover tracks from their phones. That accessibility has helped turn Mars into a familiar presence in everyday feeds, and the latest milestone has been no exception, with the new view of mesas and dunes circulating widely as a fresh example of what orbital imaging can deliver.

Some of the most enthusiastic reactions have come from communities that specialize in space imagery, where users trade favorite frames and debate which landscapes look most like deserts on Earth. One widely shared post framed the 100,000th capture as NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s HiRISE camera taking a landmark Image of the Red Planet, a phrasing that captures both the technical achievement and the emotional pull of seeing another world in such detail. That blend of rigorous data and visual drama is part of why the mission has maintained a strong public profile long after its launch.

Why this matters for the next generation of Mars missions

The timing of the 100,000th image matters because Mars exploration is entering a more complex phase, with sample return plans, new orbiters, and eventual crewed missions all on the table. Every high-resolution frame helps reduce uncertainty for those future efforts, whether by refining maps of potential sample caches or by identifying hazards that could threaten landers and habitats. I see the milestone as a reminder that the infrastructure for future missions is already in place, quietly building the reference library that new spacecraft will depend on from the moment they arrive.

That role extends beyond NASA’s own hardware. International partners and commercial players looking at Mars can draw on the same datasets, using HiRISE images to cross-check their own observations or to scout regions that align with their goals. Coverage of the milestone has emphasized how Photographs from the orbiter do double duty, illustrating the grandeur of the Red Planet while also providing the fine-grained details that engineers and scientists need. In that sense, the 100,000th image is both a celebration of what has been accomplished and a building block for what comes next.

A mission that keeps outperforming its design

Underneath the headlines about image counts and terabits of data is a quieter story about engineering resilience. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter was not originally built to operate for decades, yet it has continued to function well beyond its intended design life, a fact that has allowed instruments like HiRISE to reach milestones that would have been hard to imagine at launch. Careful management of fuel, power, and thermal conditions has kept the spacecraft stable in its orbit, enabling the steady cadence of imaging that culminated in the 100,000th frame.

That performance has turned the orbiter into a case study in how to stretch the value of a flagship mission. Each additional year of operation multiplies the return on the original investment, especially when the spacecraft can keep supporting new landers and rovers as they arrive. The mission’s track record, documented in over Decades of continuous service and more than 100,000 high-resolution images, sets a high bar for future orbiters around Mars and other worlds. It shows that with robust design and careful operations, a single spacecraft can reshape our understanding of a planet, one image at a time.

More from MorningOverview