Human navigation turns out to be less like following a static map and more like tuning a control knob inside the brain. New imaging work suggests that deep in the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure crucial for memory, activity ramps up along a gradient that tracks how familiar or unfamiliar a place feels, effectively acting as an internal “dial” that helps people stay oriented. That discovery slots into a broader wave of research showing that the brain runs a surprisingly sophisticated guidance system, complete with a neural compass, mental maps and rapid-fire simulations of possible routes.

As I look across these studies, a consistent picture emerges: the sense of direction is not a single talent but a coordinated network that blends memory, perception and movement into a constantly updated estimate of “where I am” and “which way I am facing.” Understanding that system is not just a curiosity for people who like to hike off-trail or navigate subway transfers without Google Maps, it is also reshaping how scientists think about Alzheimer’s disease, virtual reality design and even the way smartphones might one day support a failing internal compass.

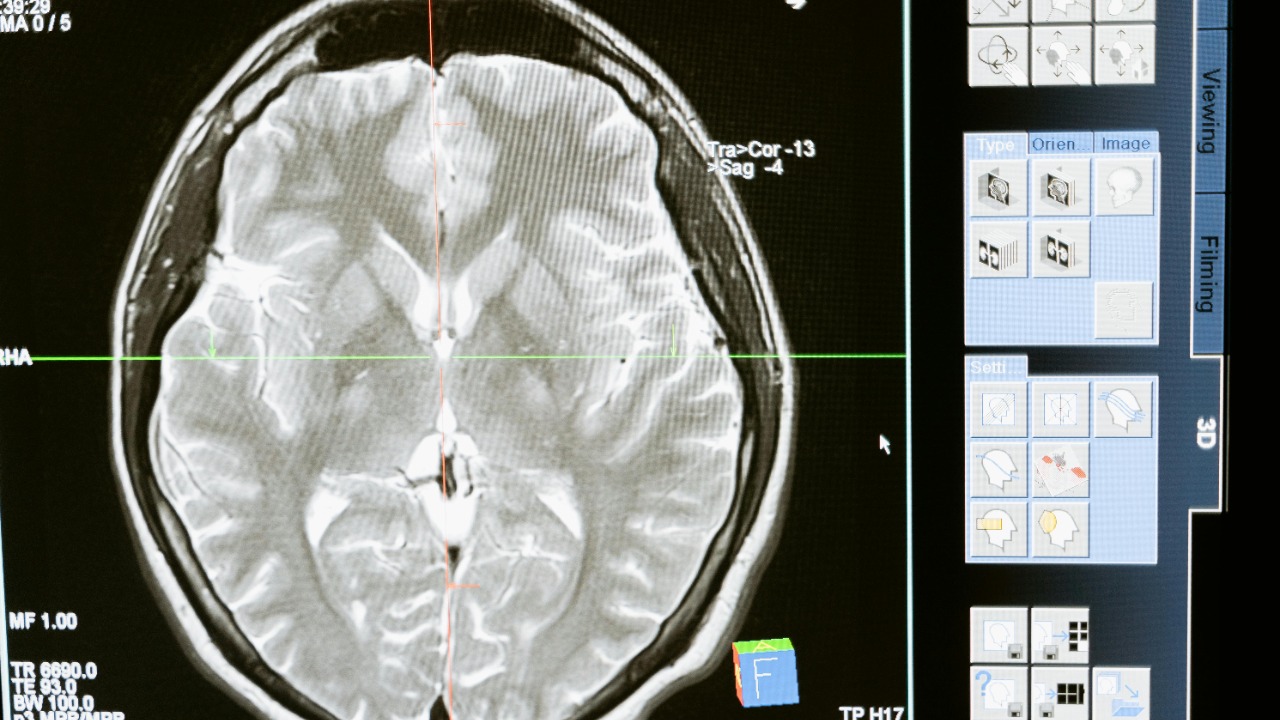

The hippocampal “dial” that tracks familiarity

The most striking new finding comes from brain scans that zoomed in on the hippocampus while people navigated environments that ranged from well known to completely new. Researchers reported that activity in this region did not simply switch on or off when a person recognized a place, it changed smoothly along a gradient that ran from familiar to unfamiliar, like a dimmer switch rather than a light. In other words, the hippocampus appeared to encode how strongly a scene was anchored in memory, effectively turning up or down an internal gauge of environmental familiarity as people moved through space, a pattern highlighted in detailed imaging of the seahorse-shaped hippocampus.

That gradient matters because it gives the navigation system a way to decide when to lean on memory and when to treat a situation as novel. When the “dial” is turned toward the familiar end, the brain can reuse well worn routes, like the path from your front door to your kitchen, with minimal effort. As it swings toward the unfamiliar, other circuits that support exploration and careful visual scanning appear to take on a larger role, helping people avoid getting lost in a new neighborhood or a confusing airport terminal, a dynamic that becomes especially important when the same hippocampal circuits are disrupted early in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, as described in work on how this brain-scan study reveals key components of navigation.

A neural compass that keeps heading on track

Of course, knowing whether a place feels familiar is only half the problem, the brain also has to keep track of which way the body is facing. Earlier this year, researchers identified a pattern of activity that functions as a neural compass, maintaining a stable representation of heading direction even as people move through complex scenes. This pattern, observed while volunteers navigated and then recalled routes, suggested that specific populations of neurons fire in relation to facing direction rather than to particular landmarks, providing a reference frame that stays aligned with the world as the person turns, a mechanism described as a pattern of brain activity that helps prevent us from getting lost.

Follow up reporting on the same line of work underscored that this compass-like signal is not confined to a single tiny patch of tissue but involves a broader network that includes regions in and around the hippocampus. Scientists described how this activity allowed people to stay oriented even when visual cues were limited or misleading, a crucial ability when walking through a crowded subway station or driving through a foggy stretch of highway. By pinpointing this neural compass of brain activity used to orient people, the research helps explain why some neurological disorders leave patients disoriented even in otherwise familiar surroundings.

Why the brain’s internal compass is more complex than a simple GPS

It is tempting to compare this system to the blue dot on a smartphone map, but the biology is more intricate than a single GPS chip. Work from cognitive scientists has shown that the brain’s internal compass integrates multiple streams of information, including visual landmarks, self-motion cues from the inner ear and even expectations about where a path should lead. In controlled experiments, people navigating virtual environments showed patterns of neural activity that shifted not only with their physical direction but also with changes in the layout and context of the scene, revealing that the internal compass is sensitive to the structure of space itself, a complexity highlighted in research arguing that the brain’s internal compass is more complex than once thought.

That complexity has real world implications. As virtual reality headsets like the Meta Quest 3 or Apple Vision Pro become more common, people are spending more time in artificial spaces that can either support or confuse the internal compass. The same research community has warned that poorly designed virtual environments, with inconsistent landmarks or impossible geometries, may strain the navigation system and contribute to motion sickness or disorientation. By understanding how the compass responds to cues such as a simple vertical white line on a wall or the alignment of corridors, designers can build virtual worlds that respect the way the brain organizes space, a concern that becomes more pressing as the spread of virtual reality technology accelerates.

Virtual reality as a laboratory for the neural compass

One of the most powerful tools for probing the navigation system has turned out to be virtual reality itself. By placing volunteers in carefully controlled digital environments, scientists can manipulate landmarks, paths and viewpoints in ways that would be impossible or unsafe in the real world, then watch how the brain responds. In work led by Zhengang Lu and Russell Epstein from the University of Pennsylvania, participants explored virtual spaces while their brain activity was recorded, allowing the team to identify regions whose firing patterns tracked heading direction and spatial layout, effectively using immersive simulations to discover the brain’s internal compass through virtual reality.

Those experiments, presented under the umbrella of the Society for Neuroscience, showed that the same circuits that guide people through real streets can also anchor them in digital cities, provided the virtual world obeys consistent spatial rules. That finding is encouraging for developers who want to build training simulations for pilots, surgeons or first responders, because it suggests that practice in a headset can engage the genuine navigation machinery rather than a separate, game specific system. At the same time, the work underscores how fragile the sense of direction can be when cues are sparse or contradictory, a lesson that matters for anyone designing virtual tours, educational games or even the layout of a 3D shopping mall inside a headset.

The building blocks: place cells, grid cells and goal-direction cells

Underneath these large scale patterns lie individual neurons that behave like the pixels of the brain’s map. Decades of work in rodents and humans have identified “place cells” that fire when an animal occupies a specific location and “grid cells” that activate in a repeating lattice as the animal moves, together forming a coordinate system for space. More recent research has added another layer, “goal-direction cells” that become active when the animal is oriented toward a target, effectively encoding not just where you are and which way you are facing but where you intend to go, a trio of cell types that help build the brain cells behind a sense of direction.

When I think about everyday navigation, from choosing an exit in a multi level parking garage to finding a specific gate in an unfamiliar airport, these cells look like the microscopic foundation of those choices. Place cells can tell you that you are near the elevators, grid cells can track how far you have walked since leaving your car, and goal-direction cells can bias your movements toward the sign that points to Gate 32B. Together, they allow the hippocampal “dial” and the broader neural compass network to translate abstract goals into concrete steps, a process that becomes painfully visible when it fails in people who wander or become lost in early dementia.

Naturalistic navigation and the brain’s heading signal

Laboratory tasks are useful, but they can only approximate the complexity of real life movement. To bridge that gap, some teams have begun recording brain activity while people navigate more naturalistic, dynamic environments, such as walking through a building or driving along a winding road. In one such study, scientists focused on how the brain maintains a consistent representation of facing direction even as the visual scene changes rapidly, identifying a robust heading signal that persisted across different contexts and tasks, a pattern described in an abstract on a neural compass in the human brain during naturalistic navigation.

Those findings help explain why people can keep track of north even when they are not looking at a compass or a landmark like the sun. The heading signal appears to integrate internal cues from the vestibular system, which senses rotation and acceleration, with external cues from vision and touch, such as the feel of a turn in the steering wheel of a 2024 Toyota RAV4 or the sight of a familiar church steeple at the end of a street. When that integration breaks down, as it can in certain vestibular disorders or after a concussion, patients often report feeling “spun around” or unable to maintain a sense of direction, even in places they know well.

Flickering between old maps and new routes

Another piece of the puzzle comes from work showing that the hippocampus does not simply overwrite old maps when it encounters a new environment. Instead, it appears to flicker between representations, rapidly alternating activity patterns that correspond to past experiences and the current scene. In experiments where people navigated unfamiliar routes, researchers observed that the brain briefly reactivated older maps, as if testing whether a known layout could be repurposed, before settling into a new configuration, a process described as the brain navigating new spaces by flickering between reality and old mental maps.

That flickering may be the neural basis for the familiar feeling that a new city “reminds you” of somewhere you have been before. When I walk through a neighborhood in Lisbon that feels like a cross between San Francisco and Naples, the hippocampus may be briefly imposing those older maps on the new streets, using them as templates to speed up learning. The same mechanism could help explain why people sometimes take a wrong turn that would have been correct in a different city or building, a kind of mental autocomplete that usually helps but occasionally misfires.

Two key regions that act as a neural GPS

As imaging methods improve, scientists are also getting more precise about which brain regions contribute to the sense of direction. In one recent report, researchers described how two specific areas worked together as a kind of neural GPS, keeping people oriented while they navigated a virtual city. Activity in these regions tracked both the person’s current heading and their position relative to key landmarks, and disruptions in this network were linked to difficulties in wayfinding, a pattern summarized in work showing that researchers discovered two brain regions that work as a neural compass.

Those findings dovetail with clinical observations that damage to particular parts of the temporal and parietal lobes can leave patients unable to form new spatial memories or to use landmarks effectively, even when their vision and general intelligence remain intact. By tying those deficits to specific nodes in the navigation network, the work opens the door to more targeted rehabilitation strategies, such as training programs that emphasize alternative cues or technologies that provide extra directional feedback through smartphone apps, smartwatches or even haptic belts that vibrate when the wearer drifts off course.

Navigation, memory and the early signs of Alzheimer’s

Perhaps the most sobering thread running through this research is the tight link between navigation and memory. The hippocampus is one of the first regions to be affected in Alzheimer’s disease, and clinicians have long noted that people in the early stages often struggle with wayfinding, even before more obvious memory problems appear. The new work on the hippocampal “dial” suggests a possible mechanism: if the gradient that tracks familiarity begins to fail, patients may lose the ability to distinguish between well known and unfamiliar places, making even a short walk to the corner store feel uncertain, a concern raised in reporting that the brain areas that help navigation are affected in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

For clinicians and families, that connection offers both a warning and an opportunity. Subtle changes in how someone navigates, such as getting turned around on a route they have driven for years or relying heavily on turn by turn directions from apps like Waze or Apple Maps for simple trips, could serve as early red flags that prompt further evaluation. At the same time, therapies that strengthen spatial memory, from structured wayfinding exercises in assisted living facilities to virtual reality training programs that gently challenge the internal compass, might help preserve independence a little longer, even if they cannot halt the underlying disease.

Designing worlds that work with, not against, the brain’s compass

All of this research points to a practical takeaway: the built environments we move through every day can either support or sabotage the brain’s navigation system. Clear sightlines, distinctive landmarks and consistent layouts make it easier for the hippocampal “dial” and the neural compass to stay calibrated, while confusing floor plans, repetitive corridors and poor signage force the brain to work harder. Architects and urban planners are beginning to pay closer attention to these findings, recognizing that good design can reduce cognitive load for everyone and may be especially important for older adults or people with neurological conditions, a perspective reinforced by work on reading the brain’s internal compass in the context of real and virtual spaces.

As I see it, the emerging science of navigation is quietly reshaping fields as diverse as game design, transportation planning and dementia care. When a subway system like Tokyo’s uses color coded lines and distinctive station icons, or when a hospital adds large, easily recognizable symbols to each wing, those choices are not just aesthetic, they are interventions in the brain’s guidance system. The more we learn about the internal “dial” that tracks familiarity, the compass that keeps heading aligned and the cells that encode goals, the better equipped we will be to build cities, apps and devices that respect the way the brain actually finds its way through the world.

More from MorningOverview