The James Webb Space Telescope has caught what appears to be the earliest supernova humanity has ever seen, a stellar death flash from a time when the universe itself was still in its cosmic childhood. If the interpretation holds, it will not just reset the record books, it will open a new window on how the very first generations of stars lived and died.

By tracing this ancient explosion and the fragile galaxy that hosted it, astronomers are starting to turn a once abstract era of “cosmic dawn” into a place they can actually map, measure, and test. I see this result as a turning point, where Webb stops merely spotting distant smudges of light and begins following individual stars through their final, spectacular moments.

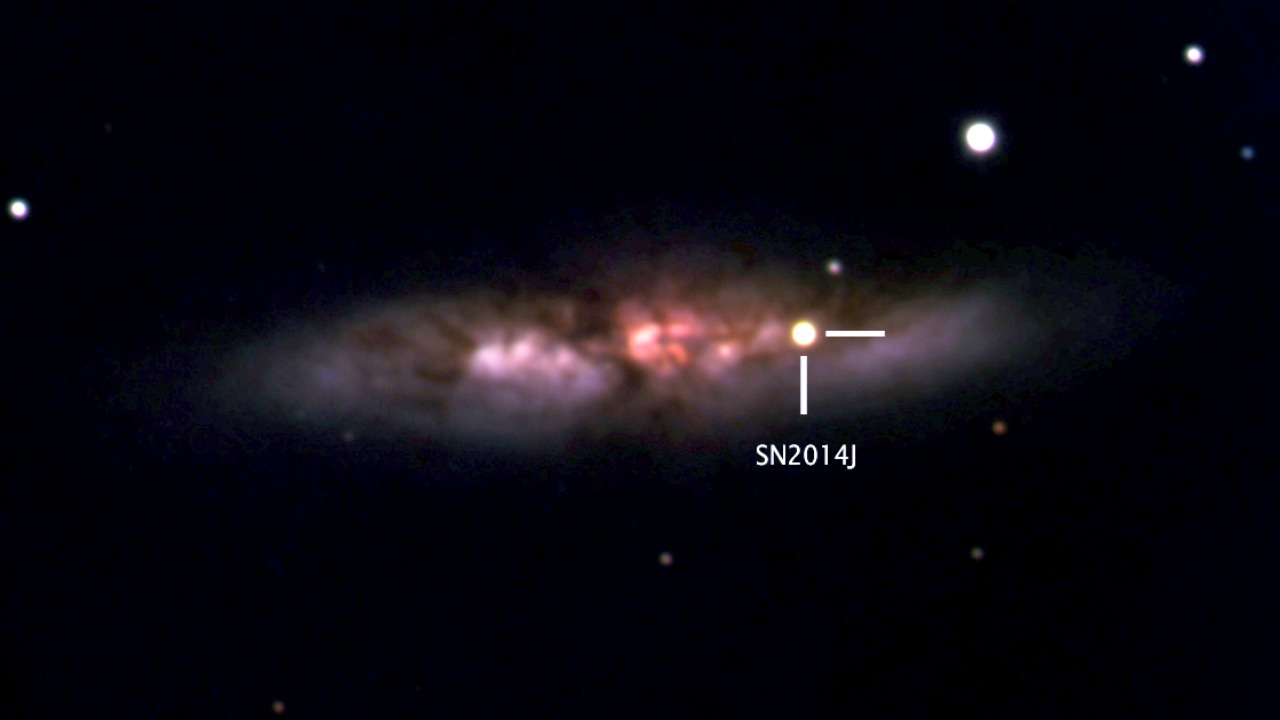

Webb’s record-breaking blast from a 5 percent–old universe

The core claim behind the new result is stark: astronomers have identified a supernova that detonated when the universe was only about 5 percent of its current age, making it the most ancient stellar explosion ever observed. In practical terms, that means the light left the blast more than 13 billion years ago, then spent nearly the entire history of the cosmos crossing expanding space before finally hitting Webb’s detectors. I see that timing as crucial, because it pushes supernova science into the same epoch where researchers are already hunting the earliest galaxies and the first sustained bursts of star formation.

To reach that conclusion, the team relied on the sensitivity of the James Webb Space Telescope, often shortened to JWST, which was built precisely to capture faint infrared light from such extreme distances. Reporting on the discovery notes that JWST recorded the fading glow of this explosion and tied it to a host galaxy that existed when the universe was only 5 percent of its present age, confirming that this is the earliest supernova yet seen and placing it squarely in the era when the first generations of stars were reshaping the young cosmos through their radiation and their violent deaths, as detailed in coverage of how JWST captures the earliest supernova yet.

How a distant gamma-ray burst led Webb to the explosion

The story of this supernova does not begin with Webb, it starts with a powerful flash of high-energy light that swept past Earth earlier this year. Satellites that monitor the sky for gamma rays picked up a burst so distant that its origin was immediately flagged as a potential probe of the early universe. I see that initial detection as the trigger for everything that followed, because without it, the host galaxy would have remained just one more faint speck in a crowded Webb field.

Follow-up observations with the James Webb Space Telescope then traced that gamma-ray burst back to its source, revealing that the explosion came from a galaxy seen at a time when the universe was only a small fraction of its current age. Detailed accounts describe how, earlier this year, a powerful gamma-ray burst traveled through space from a very distant source, and how Webb traced that distant explosion to what is now recognized as the oldest supernova ever observed, in a universe that was about 5 percent of its current age, a sequence laid out in reporting that Webb traces distant explosion to oldest supernova.

The NASA, ESA, CSA powerhouse behind the discovery

Behind the poetic image of a dying star from cosmic dawn sits a very concrete machine and a very specific partnership. The observatory that caught this event is officially known as The NASA, ESA, CSA, James Webb Space Telescope, a joint project of the United States, Europe, and Canada that was designed from the start to push into exactly this regime of early-universe science. I see that multinational structure as more than a funding detail, because it shapes the way data are shared, teams are formed, and discoveries like this one are vetted and announced.

According to mission reports, Webb’s instruments were able to identify the earliest supernova to date and reveal its host galaxy, then track how the light from the blast brightened and faded over weeks before it slowly dimmed out of view. That careful monitoring, carried out by The NASA, ESA, CSA, James Webb Space Telescope, is what allowed astronomers to confirm that they were seeing a genuine supernova and not some other transient flare, as described in mission updates that explain how The NASA, ESA, CSA, James Webb Space Telescope identified the earliest supernova to date and followed its fading light over several weeks before it slowly dims.

A fragile host galaxy at the dawn of star formation

Every supernova needs a home, and in this case the host galaxy is as scientifically valuable as the explosion itself. The galaxy that cradled this dying star appears as a tiny, distant system, the kind of object that would have been invisible to previous space telescopes but now falls squarely within Webb’s reach. I see that as a reminder that the early universe was not dominated by grand spirals like the Milky Way, but by small, rapidly evolving galaxies where a single massive star’s death could significantly reshape the local environment.

Researchers describe this host as part of the population of very distant galaxies that Webb is now cataloging, alongside other record-setting systems that rank among the two oldest and most distant galaxies ever seen. By tying the supernova to such a remote galaxy, astronomers can compare its properties to those of other early systems that Webb has already identified, including the two oldest, most distant galaxies reported in studies of two oldest, most distant galaxies, and start to build a more complete picture of how star formation and stellar death unfolded in the first few hundred million years.

What the light curve reveals about the star that died

To move from “bright flash” to “earliest supernova,” astronomers had to show that the fading light followed the pattern expected from a star’s explosive death. That pattern, known as a light curve, tracks how the brightness rises, peaks, and then declines over time as radioactive elements forged in the blast decay and the expanding debris cloud cools. I see the shape of that curve as the key forensic tool in this case, because it encodes information about the mass of the star, the type of explosion, and the environment around it.

In this event, Webb’s repeated observations captured the glow of the supernova for weeks before it slowly dimmed, a behavior that matches the expected evolution of a stellar explosion rather than a brief flare from an active black hole or some other transient. Mission accounts emphasize that Webb identified the earliest supernova to date and then showed its host galaxy while tracking the light for weeks before it slowly dims, a sequence that allowed the team to classify the event as a supernova and to begin inferring the properties of the star that died, as detailed in the description of how Webb followed the supernova’s light over time.

A coordinated international team and a 110-day window

Capturing a supernova at this distance is not just a matter of pointing a telescope and getting lucky, it requires a coordinated response from an international team that can move quickly when a promising signal appears. In this case, astronomers from multiple institutions organized follow-up observations with Webb and other facilities to make sure they did not miss the crucial early phases of the explosion. I see that rapid coordination as a proof of concept for how the community can use Webb as a time-domain observatory, not only a static camera for deep fields.

Reports from the collaboration describe how an international team of astronomers used the James Webb Space Te to probe the early universe, tracking the aftermath of the burst for up to 110 days after the initial flash. That 110-day window gave them enough data to map the evolution of the supernova’s light and to separate the transient glow from the steady emission of the host galaxy, a strategy laid out in accounts of how an international team of astronomers used the James Webb Space Te to follow the event for 110 days after the burst.

Why the earliest supernova matters for galaxy evolution

Finding a single supernova at such an early epoch might sound like a curiosity, but its implications reach far beyond one dying star. Supernovae are the engines that enrich galaxies with heavy elements, stir up gas, and sometimes even blow material out into intergalactic space, so catching one when the universe was only 5 percent of its current age gives astronomers a direct look at how those processes started. I see this event as a rare chance to test theories about how quickly the first stars seeded their surroundings with the ingredients for planets, life, and later generations of stars.

By comparing the properties of this explosion and its host galaxy to other early systems that Webb has found, including the two oldest, most distant galaxies and other young star-forming regions, researchers can start to quantify how often massive stars were dying and how much energy they were injecting into their environments. Studies that highlight how JWST captures the earliest supernova yet and how it is already revealing stars in the early universe, alongside work on the two oldest, most distant galaxies, show that Webb is beginning to connect the dots between the birth of the first galaxies and the deaths of their most massive stars, a link that will be essential for any complete model of early galaxy evolution, as seen in analyses of stars in the early universe.

From record-breaking galaxies to record-breaking deaths

Webb’s early fame came from its images of extraordinarily distant galaxies, some of which appeared surprisingly massive and mature for their age. Those discoveries raised questions about whether our models of early star formation were missing something, or whether some of the candidates were being misinterpreted. I see the new supernova result as a natural next step, because it shifts the focus from counting galaxies to dissecting the life cycles of the stars inside them.

In the same way that Webb has already identified the two oldest, most distant galaxies, it is now starting to log the earliest known examples of stellar deaths, tying them to specific host systems and epochs. By moving from static snapshots of faraway galaxies to time-resolved studies of events like this supernova, Webb is turning the early universe into a dynamic laboratory, where astronomers can watch how individual stars live, die, and reshape their surroundings, a progression that builds directly on the catalog of two oldest, most distant galaxies and extends it into the realm of explosive transients.

What comes next for Webb and the first stars

If Webb can find one supernova from a universe at 5 percent of its current age, it is almost certain that more are hiding in its data or waiting to appear in future observations. Each new detection will help fill in the statistical picture, revealing how common such explosions were, what kinds of stars produced them, and how they varied from one early galaxy to another. I see the current discovery as a proof that the technique works, and as a signal that the era of routine supernova studies at cosmic dawn is about to begin.

Future campaigns will likely combine rapid alerts from gamma-ray satellites with targeted Webb follow-up, as in the case where earlier this year a powerful gamma-ray burst led to the identification of the oldest supernova ever observed, and with longer term monitoring like the 110-day campaign carried out by the international team using the James Webb Space Te. As those efforts ramp up, astronomers will be able to map not only the earliest galaxies and the earliest supernovae, but also the feedback loop between them, turning what was once an unreachable chapter of cosmic history into a well observed, data rich field of study.

More from MorningOverview