Osteoarthritis is one of the most expensive and disabling conditions in modern medicine, driving joint replacements and chronic pain that reshape daily life for millions of people. Now a new cell therapy built from lab-grown neurons is being tested as a kind of living “sponge” that soaks up inflammatory pain signals inside the joint while also helping to preserve the fragile cartilage those joints depend on.

Instead of simply numbing pain, this approach aims to intercept the molecular messengers that keep osteoarthritis smoldering, potentially slowing the disease while reducing the need for opioids and repeated injections. I see it as part of a broader shift in orthopedics, where biologic and biomaterial tools are converging to protect cartilage rather than just patch it once it fails.

The burden of osteoarthritis and the limits of current care

Osteoarthritis is not just a sore knee after a long run, it is a structural breakdown of cartilage that drives swelling, stiffness, and grinding pain with every step. In the United States alone, osteoarthritis, often shortened to OA, accounts for In the neighborhood of $65 billion in direct and indirect costs, with over 1 million joint replacements each year as people exhaust conservative options. Those numbers reflect a system that still leans heavily on painkillers, steroid injections, and eventually metal and plastic implants once cartilage is too damaged to salvage.

Even the more advanced biologic treatments in routine use today tend to offer symptom relief rather than true regeneration. Platelet-rich plasma injections, often marketed as a way to “heal” joints, have shown some promise in knee osteoarthritis, but as of 2025 the evidence still frames them as a tool to modestly improve pain and function rather than a cure. Clinical summaries of Using PRP To Treat Knee Osteoarthritis describe outcomes that depend heavily on patient selection, injection protocols, and combination with other techniques, underscoring how far the field still is from a universally reliable, disease-modifying therapy.

Why cartilage is so hard to save

Part of the problem is biological: cartilage is a specialized, avascular tissue that does not repair itself easily once injured. Reviews such as Cartilage Repair in 2025: Hope, Hype, or Horizon? lay out an Overview of Current Cartilage Repair Modalities that includes microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation, and osteochondral grafts, each with trade-offs in durability, cost, and technical complexity. Early clinical evidence indicates that some of these techniques can fill focal defects, but long-term safety and efficacy in diffuse osteoarthritis remain uncertain.

Researchers have responded by designing ever more sophisticated scaffolds that try to mimic the layered structure of native cartilage. Work on Biomimetic multizonal scaffolds describes a sponge-like geometric arrangement that can withstand localized forces transmitted through the bone while a porous structure promotes nutrient flow and cell infiltration. Yet even with such engineering advances, the inflammatory environment of an osteoarthritic joint can sabotage repair, which is why a therapy that can both protect cartilage and dial down pain signaling inside that environment is so intriguing.

From stem cells to nociceptors: how the “pain sponge” is built

The new “sponge” concept comes from a different corner of regenerative medicine, one that focuses on neurons rather than cartilage cells. SereNeuro Therapeutics has reported that its candidate SN101 is a first-in-class therapy derived from induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs, which are reprogrammed adult cells capable of becoming many tissue types. According to early data, SereNeuro Therapeutics revealed promising results for SN101 as a first-in-class iPSC-derived therapy designed to treat chronic osteoarthritis pain without relying on opioids or systemic nerve-blocking drugs.

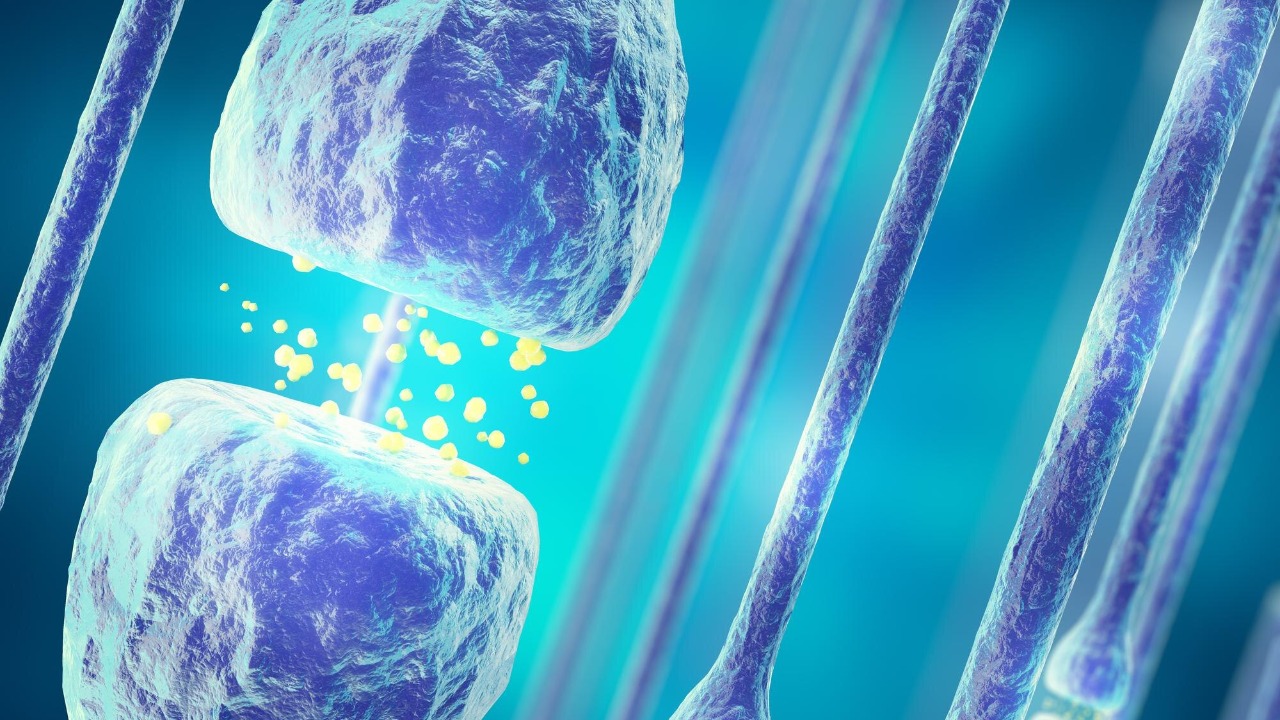

What makes SN101 unusual is that it is composed of high-purity nociceptors, the sensory neurons that normally detect painful stimuli. In this case, the cells are engineered to act less like alarm bells and more like molecular sponges. As one description of the platform puts it, Our approach utilizes high-purity, iPSC-derived nociceptors (SN101) that effectively function as a sponge for pain factors inside the joint, positioning the therapy as a potential disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) rather than a simple analgesic.

How a neuronal “sponge” can mute pain and protect cartilage

At the mechanistic level, the idea is deceptively simple: instead of blocking pain signals after they reach the nervous system, intercept the inflammatory molecules that trigger those signals in the first place. Reports from preclinical and early translational work describe SN101 neurons that function as a therapeutic sponge by sequestering inflammatory pain factors without transmitting pain signals themselves. In other words, the cells soak up cytokines and other mediators that would normally activate native nociceptors, but they are wired not to pass that alarm on to the brain.

That same mechanism appears to have knock-on effects for joint structure. By reducing the concentration of inflammatory factors, the therapy seems to slow the biochemical cascade that erodes cartilage over time. Data presented through the SN101 neurons program indicate that this non-opioid “pain sponge” therapy can halt cartilage degeneration and relieve chronic pain by using the implanted neurons to downregulate pain and inflammation inside the joint microenvironment.

Early results: less pain, healthier joints, fewer opioids

For patients and clinicians, the most compelling question is whether this elegant biology translates into real-world relief. Early reports suggest that SN101 can reduce chronic osteoarthritis pain while also preserving joint structure, at least in the models studied so far. SereNeuro’s initial data package describes reductions in pain behaviors and imaging signs of cartilage breakdown, positioning SN101 as a candidate that could change the trajectory of disease rather than simply masking symptoms.

The opioid angle is equally important. Chronic joint pain is one of the pathways that leads people onto long-term opioid regimens, with all the attendant risks of dependence, overdose, and diminished quality of life. A Baltimore-based startup working with this platform has highlighted how the cell therapy could offer an opioid-free alternative by absorbing pain signals at their source. According to New data presented at ISSCR, the novel Pain Sponge technology both relieves osteoarthritis pain and regrows cartilage, positioning it as a first-of-its-kind cell therapy that could reduce reliance on invasive and often degenerative pain treatments.

How it compares with today’s stem cell and biologic options

To understand how disruptive this approach might be, it helps to compare it with the stem cell therapies already marketed to patients. Many clinics currently offer injections of mesenchymal stem cells, often abbreviated as MSCs, for knee, hip, and spine problems, typically framed as a way to “regrow” cartilage. Yet major payers and guideline bodies remain skeptical. A policy review on Stem Cell Therapy for Orthopedic Indications notes that Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy is considered investigational for all orthopedic applications, including use in regenerative procedures for osteoarthritis, reflecting limited high-quality evidence and unresolved safety questions.

SN101 differs in both its cell type and its intended role. Rather than trying to directly replace cartilage cells, it uses iPSC-derived nociceptors as a living drug delivery and absorption system inside the joint. That puts it closer to a biologic implant than a traditional stem cell shot. At the same time, it sits alongside other biologic strategies such as PRP and growth factor injections, which, as the Evidence and Outcomes for knee osteoarthritis make clear, still show variable results and often need to be combined with physical therapy and mechanical unloading to achieve meaningful gains.

Scaffolds, foams, and the future “home” for pain sponges

One of the more intriguing possibilities is how a neuronal sponge like SN101 might be paired with next-generation scaffolds that physically support cartilage repair. Engineers are already building multizonal constructs that mimic the way cartilage transitions from a soft, lubricating surface to a stiffer, bone-facing layer. In work on Sponge-like multizonal scaffolds, researchers describe geometric arrangements that can withstand localized forces transmitted through the bone while a porous architecture allows cells and nutrients to move freely, creating a more hospitable niche for regeneration.

Parallel efforts in biomaterials are pushing toward bionic scaffolds that integrate mechanical strength with biological cues. Reviews of Substantial advancements in bionic scaffolds for cartilage tissue highlight how biomaterial-based constructs have driven osteoarthritic cartilage regeneration and are poised for extensive application in regenerative medicine. It is not hard to imagine a future procedure where surgeons implant a cartilage-mimicking scaffold seeded with chondrocytes or progenitor cells, then add a layer of SN101 nociceptors that act as a biochemical shield, absorbing inflammatory factors while the new tissue matures.

Where the science stands: hope, hype, and unanswered questions

For all the excitement, I find it important to keep the current evidence in perspective. Reviews like Hope, Hype, Horizon emphasize that early clinical evidence indicates some cartilage repair techniques can improve symptoms and imaging findings, but long-term safety and efficacy remain to be proven. The same caution applies to SN101 and related pain sponge therapies, which still need larger, longer trials to show that benefits persist, that implanted cells remain stable, and that unexpected side effects do not emerge over time.

Regulators and payers will also scrutinize how these therapies are delivered and monitored. Because SN101 uses iPSC-derived neurons, manufacturing consistency, tumorigenicity risk, and immune compatibility are all central questions. Policy documents that still classify Mesenchymal and MSC approaches as investigational signal how high the bar will be for any new cell-based orthopedic therapy. Until randomized, controlled data accumulate, the pain sponge will sit in the same category as many regenerative interventions: scientifically compelling, potentially transformative, but not yet a standard of care.

What this could mean for patients and the orthopedic playbook

If the early promise holds up, a neuronal sponge that both eases pain and shields cartilage could reshape how I think about treating osteoarthritis. Instead of a linear path from oral painkillers to injections to joint replacement, care could become more layered and biologically targeted. A patient with moderate knee disease might receive a combination of mechanical unloading, physical therapy, PRP or other biologics, and a localized SN101 implant that reduces inflammatory signaling, with the goal of delaying or avoiding surgery altogether.

Even for those who eventually need joint replacement, better control of inflammation and pain beforehand could improve function and quality of life in the years leading up to surgery. The broader ecosystem of regenerative tools, from graphene-based foams that support lab-grown cartilage to bionic scaffolds and iPSC-derived cells, is moving toward a future where joints are managed as living ecosystems rather than simple hinges to be swapped out. As the data on the Pain Sponge platform, SereNeuro’s SN101, and related technologies mature, the central question will be whether they can deliver durable, reproducible benefits that justify their complexity and cost, and whether they can finally bend that $65 billion osteoarthritis burden in the right direction.

More from MorningOverview