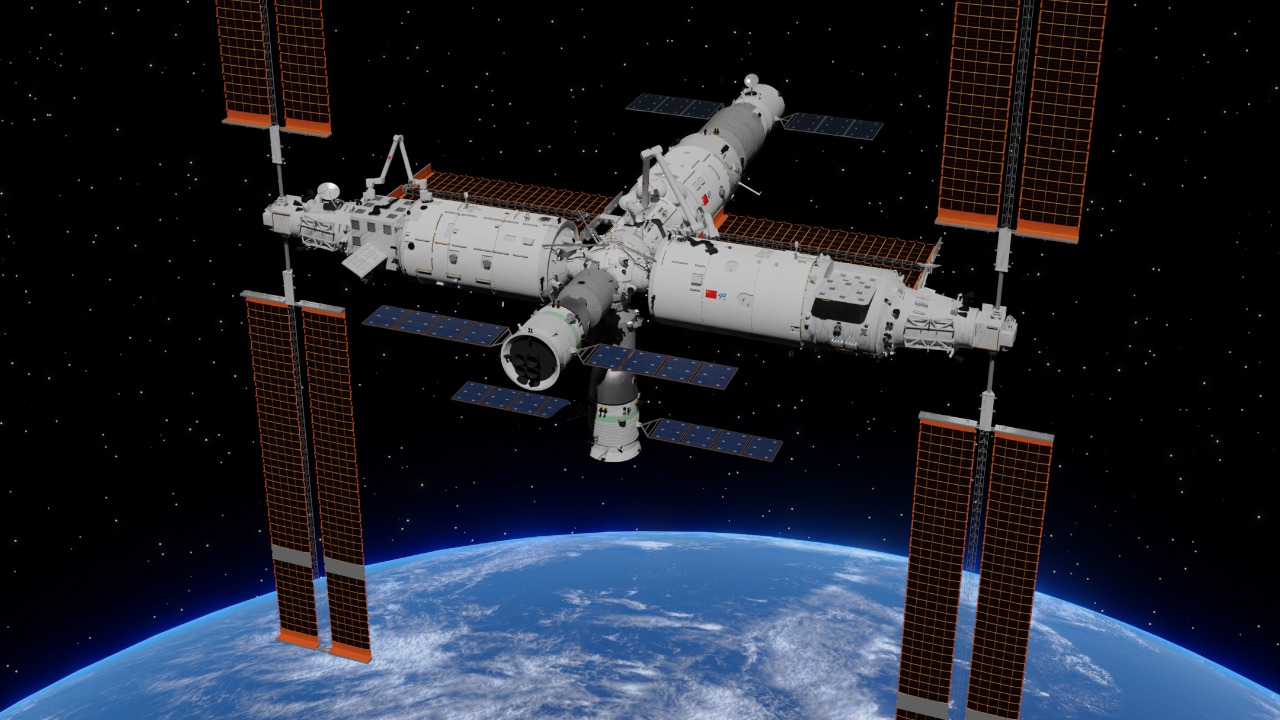

China has begun hardening its Tiangong space station against the growing threat of orbital debris, installing new layers of shielding and other defensive hardware after a series of close calls and confirmed damage in orbit. The move signals that protecting crewed spacecraft from high speed fragments is no longer a theoretical concern but a central design priority for every major space power.

By reinforcing Tiangong’s modules and inspecting its visiting spacecraft for impact scars, Chinese mission planners are treating space junk as an operational hazard on par with launch failures or life support breakdowns. I see this shift not as an isolated engineering tweak but as part of a broader rethinking of how long term human presence in low Earth orbit can survive in an environment that is steadily filling with discarded hardware and shattered fragments.

Tiangong’s new armor and what “defensive countermeasures” really mean

When Chinese officials describe “defensive countermeasures” on Tiangong, they are talking about physical protection rather than weapons, a set of shields and structural upgrades designed to absorb or deflect impacts from small pieces of space junk. The core idea is simple: if engineers cannot reliably clear the orbit around the station, they can at least harden the outpost so that millimeter to centimeter scale fragments are less likely to puncture pressure hulls, radiators, or critical cables. That logic is now being translated into hardware bolted directly onto the station’s exterior.

Chinese crews have already carried out a focused spacewalk to add new debris shielding to the multi module complex, working outside Tiangong for roughly six hours to install panels on vulnerable areas of the station. According to Chinese state television, the taikonauts attached additional protection to the main module and other exposed structures, effectively thickening the station’s skin and giving it more capacity to withstand high velocity impacts from orbiting fragments, as detailed in reports on debris shielding. I read that operation as a clear signal that China expects Tiangong to operate in a deteriorating orbital environment for years, and is willing to invest crew time and launch mass in passive defenses that quietly stand guard around the clock.

Spacewalks that turned into damage inspections

The decision to reinforce Tiangong did not emerge in a vacuum, it followed a series of spacewalks in which Chinese astronauts were sent outside to inspect and repair hardware that had already been struck. Earlier this year, a crew left the station for an extended extravehicular activity to examine a visiting spacecraft that had suffered visible damage, treating the inspection as both a safety check and a forensic exercise to understand what kind of debris had hit their vehicle. That mission underscored how quickly a routine flight can turn into a risk assessment when orbit is crowded with untracked fragments.

In one case, Chinese astronauts spent about eight hours outside the station examining the Shenzhou 20 spacecraft, which had been left docked as a lifeboat and then found to be in questionable condition. On Nov, China launched the Shenzhou 22 spacecraft with nobody on board so that the Shenzhou 21 crew would have a safe replacement ride home, a decision that followed the detailed inspection of the damaged capsule during the first extravehicular activity of the Shenzhou 21 mission, as described in coverage of the Shenzhou 20 inspection. I see that emergency swap as a vivid example of how debris damage can ripple through mission planning, forcing uncrewed launches and reshuffling of return strategies simply to keep crews out of compromised vehicles.

From cracked windows to emergency return ships

Long before the latest shielding upgrades, Chinese engineers had already been confronted with the unnerving sight of cracks in spacecraft windows, a reminder that even small particles can leave serious scars at orbital speeds. When a crew looks out and sees a fracture line where there should be a clear view of Earth, the abstract charts of debris density suddenly become very personal, and the pressure to respond decisively grows. I interpret those incidents as the emotional backdrop to the more technical decisions about armor and backup vehicles.

According to The CMSA, the Chinese space agency, the next mission Shenzhou 22 was explicitly framed as a way to ensure a safe ride home after earlier crews reported cracks in their spacecraft window, with officials stating that the new ship would be launched at an appropriate time in the future while acknowledging that pieces from past anti satellite tests are still orbiting today, as described in accounts of cracks in the spacecraft window. That context helps explain why, when Shenzhou 20 showed signs of damage, China did not hesitate to send up Shenzhou 22 uncrewed and treat the older vehicle as unsafe for the return voyage, a sequence later described in detail in reports on how China installs defensive countermeasures. In my view, that pattern of cracked windows, damaged capsules, and replacement ships forms the lived experience that now drives the push to armor Tiangong itself.

How Tiangong’s defenses compare with the International Space Station

China’s new shielding strategy fits into a broader playbook that other orbital outposts have already been forced to adopt, particularly The International Space Station, which has spent years dodging debris and patching up minor impacts. The ISS is equipped with layered Whipple shields and other protective systems, yet even with that armor it still has to maneuver regularly to avoid larger tracked objects, a reminder that passive defenses alone cannot solve the problem. When I look at Tiangong’s upgrades, I see China essentially compressing decades of ISS lessons into a shorter timeline.

Reports on a recent Chinese spacewalk note that The International Space Station has to repeatedly fire its thrusters to avoid colliding with space junk, a routine that has become part of normal operations for the multinational outpost, as highlighted in coverage of Chinese astronauts clambering outside the station. By contrast, Tiangong is newer and smaller, which gives Chinese controllers more flexibility to adjust its orbit but also means that every kilogram of added shielding is a more noticeable fraction of the total mass. I read China’s decision to add armor so early in Tiangong’s life as a sign that it expects the debris environment to worsen, not stabilize, and is trying to front load protection rather than retrofit it later.

What the latest spacewalks added to Tiangong’s hull

The most visible expression of China’s new defensive posture came during a six hour extravehicular activity in which taikonauts methodically attached debris panels to Tiangong’s exterior. Working in pairs, they moved along handrails and work sites that had been designed into the station from the start, indicating that engineers had anticipated the need for future upgrades even if the exact configuration of shields was not yet fixed. I see that modularity as a quiet but important design choice, one that treats the station’s armor as something that can evolve over time.

Chinese state television reported that the crew added debris shielding to key parts of the Tiangong complex, including the main module and other exposed sections of the three module station, a task that was captured in video and described as part of a broader effort to strengthen the outpost, as detailed in coverage of how Chinese astronauts add debris shielding. The work was framed domestically as a routine maintenance task, but the choice of focus areas suggests that mission planners are particularly worried about impacts near docking ports and life support systems, where even small punctures could have outsized consequences. In my assessment, these targeted reinforcements are less about making Tiangong invulnerable and more about buying precious minutes and options if something does go wrong.

Why Chinese officials now talk openly about “defensive countermeasures”

For years, Chinese space officials tended to emphasize the peaceful, scientific nature of Tiangong, highlighting experiments and technology demonstrations rather than operational hazards. The recent shift in language toward “defensive countermeasures” reflects a more candid acknowledgment that low Earth orbit has become a contested and cluttered environment where safety cannot be taken for granted. I interpret this rhetorical change as part of a broader normalization of risk management in spaceflight, where talking about armor and backup ships is no longer seen as undermining the narrative of progress.

According to state media network CGTN, the country has now installed defensive countermeasures on the station and framed them as a necessary response to the growing threat of space debris, a message that was relayed in reports that also carried unrelated headlines such as Should You Leave Assets to Your Children in a Trust or as a Gift but clearly quoted officials saying that the new hardware was meant to protect the crew, as summarized in coverage that noted how According to state media network CGTN the countermeasures were now in place. I see that public framing as a way to reassure domestic audiences that the government is taking concrete steps to safeguard its astronauts while also signaling to international partners and competitors that China is prepared to operate in a harsher orbital environment.

The human factor: Chinese crews working outside in a shooting gallery

Behind the technical language of shields and countermeasures are the astronauts who have to venture outside the station to install them, often spending six to eight hours in bulky suits while fragments zip past at several kilometers per second. Every time a Chinese crew steps out onto Tiangong’s exterior, they are balancing the need to strengthen the station against the risk that an untracked piece of debris could strike them or their equipment. I find it telling that, despite those dangers, mission planners have repeatedly scheduled long spacewalks focused specifically on debris related tasks rather than limiting EVAs to scientific or assembly work.

Chinese reports aimed at younger audiences have even highlighted how Astronauts from the Chinese program have installed protection against space junk on their orbiting home, explaining that the new hardware is meant to shield the station from tiny pieces of metal and rock that travel at incredible speeds, as described in a Newsround style explainer that noted how Chinese astronauts have installed protection. By presenting these spacewalks as both heroic and necessary, Chinese media are helping to normalize the idea that living in orbit now requires constant vigilance and hands on maintenance, not just scientific curiosity.

Global stakes: when one country’s debris becomes everyone’s problem

China’s decision to armor Tiangong is not just a national story, it is a symptom of a global problem in which every major spacefaring nation contributes to and suffers from the same cloud of debris. Fragments from past anti satellite tests, upper stage explosions, and satellite collisions do not respect national boundaries, and a piece created by one country can just as easily threaten another’s spacecraft years later. I see Tiangong’s new defenses as a physical acknowledgment that the era of a relatively clean low Earth orbit is over.

The shared nature of the risk is evident in recent tensions between commercial operators and governments, including a case in which SpaceX was reportedly furious at China after one of its satellites came uncomfortably close to a Chinese spacecraft, prompting public complaints about collision risks. According to Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, one or two of these internet satellites fall back to Earth every day and the sheer number of objects in orbit means that it is not a question of if but when more serious incidents occur, as outlined in analysis of how SpaceX was furious at China. In that context, China’s move to shield Tiangong is both a defensive reaction to other actors’ behavior and a reminder that its own past actions, including debris generating tests, are part of the same feedback loop.

A new normal for long term human presence in low Earth orbit

As I look across the recent sequence of cracked windows, damaged capsules, emergency replacement ships, and now reinforced station modules, a clear pattern emerges: long term human presence in low Earth orbit is entering a phase where debris management is as central as propulsion or life support. For China, that means Tiangong can no longer be treated as a pristine laboratory circling a quiet planet, it is a crewed outpost operating in a shooting gallery of its own making and that of others. The installation of defensive countermeasures is therefore less a one off news event and more the opening chapter of a long campaign to keep the station habitable.

China’s recent emergency flight, in which the Shenzhou 21 crew received a new return vessel, the Shenzhou 22, after their previous ship was deemed unsafe for the return voyage, illustrates how far mission planners are now willing to go to stay ahead of the debris threat, as described in detailed accounts of how Thankfully the emergency flight was a success. Combined with the six hour spacewalks to bolt on new shielding and the public acknowledgment of “defensive countermeasures,” that willingness suggests that Tiangong’s future will be defined as much by how effectively China can defend it as by the science conducted inside. In practical terms, the station is becoming a test bed not only for microgravity research but also for the art of surviving in an increasingly hostile orbit.

More from MorningOverview