One of the most lethal forms of breast cancer has long shrugged off the best drugs in the oncologist’s arsenal, leaving patients with few options once standard treatments fail. Now a new generation of engineered antibodies is showing that even the most aggressive tumors can be cornered, slowed and in some preclinical models effectively stopped. Early laboratory and animal data suggest these targeted molecules can both attack tumor cells directly and rewire the immune environment that lets them thrive.

The promise is especially striking in triple-negative breast cancer, a subtype that spreads fast, resists therapy and kills disproportionately young and Black women. By homing in on specific proteins on tumor and immune cells, researchers are beginning to turn the cancer’s own biology against it, hinting at a future in which “treatment resistant” is no longer a life sentence.

Why triple-negative breast cancer is so deadly

To understand why these antibody breakthroughs matter, I first need to spell out what makes triple-negative breast cancer, often shortened to TNBC, so feared. Unlike hormone receptor positive tumors or HER2 driven disease, TNBC lacks estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and HER2 amplification, which means the powerful targeted drugs that transformed other breast cancer subtypes simply do not apply. As a result, patients are typically funneled toward chemotherapy, surgery and radiation, and when those fail, there has historically been little left to offer.

Researchers have documented that TNBC is not just harder to treat, it is biologically wired for speed and spread. In a detailed analysis of tumor behavior, the work titled Abstract Despite describes how TNBC cells show heightened proliferation, migration and altered bioenergetics, all of which fuel rapid growth and metastasis. That same research underscores a brutal reality for patients, the absence of effective therapeutic targets for TNBC has kept survival gains modest compared with other breast cancer types, even as diagnosis and general cancer therapy have advanced.

The immune microenvironment problem

Part of TNBC’s power lies not only in the tumor cells themselves but in the neighborhood they build. The immune microenvironment around these cancers is often skewed toward tolerance rather than attack, with immune cells either exhausted or actively co-opted to support tumor growth. For years, immunotherapy trials tried to jolt this environment with checkpoint inhibitors, but responses were uneven and often short lived, suggesting that simply releasing the brakes on T cells was not enough.

New antibody strategies are now zeroing in on that microenvironment as a therapeutic target in its own right. A report on a Novel antibody describes how reprogramming the cancer’s immune environment can suppress both primary tumor growth and the spread of triple-negative breast cancer, even in advanced disease. Instead of acting only as a guided missile against tumor cells, this antibody appears to retrain surrounding immune cells, turning a previously protective niche into hostile territory for the cancer.

A new class of engineered antibodies

The most eye catching progress comes from a new class of engineered antibodies designed specifically for drug resistant breast cancers. Rather than relying on the natural structure of antibodies, scientists have modified these molecules to bind one target on tumor cells and another on immune cells, effectively creating a bridge that pulls the body’s defenses into direct contact with malignant tissue. This dual targeting approach is meant to overcome the evasive tricks that let aggressive cancers hide in plain sight.

Researchers at King’s College London have been at the center of this work, reporting that their engineered antibodies proved effective in drug resistant breast cancer models by binding to proteins that are abundant in this form of cancer and simultaneously engaging immune cells. In their description of these Engineered Antibodies Prove Effective, the team explains that they designed the antibodies to make them highly selective for targets present in drug resistant tumors, aiming to spare healthy tissue while amplifying immune attack. It is a highly targeted approach against cancers that have already outmaneuvered standard drugs.

Inside the King’s College London breakthrough

The most widely discussed of these new molecules is a modified antibody developed at King’s College London that restricts the growth of aggressive and treatment resistant breast cancers in preclinical models. In laboratory experiments and animal studies, the antibody was engineered to bind immune cells on one side and cancer cells on the other, physically linking the two. That structural tweak turned a familiar therapeutic format into a kind of molecular handcuff, forcing immune cells into close proximity with tumors that had previously evaded them.

According to detailed reporting on the King’s College London discovery, the modified antibody bound immune cells more effectively and activated them both within tumors and in the bloodstream, which correlated with reduced tumor growth in aggressive breast cancer models. The group’s own account of how their Oct study unfolded describes a stepwise process, first validating binding in vitro, then moving into animal models where the antibody limited tumor expansion and showed activity even when standard treatments failed. It is early stage science, but the consistency across models has fueled cautious optimism.

How the antibody actually stops tumor growth

Mechanistically, what sets this antibody apart is not just what it targets, but how it choreographs the interaction between cancer and immunity. By binding a specific protein on tumor cells and a complementary receptor on immune cells, the molecule acts as a scaffold that stabilizes the immune synapse, the contact point where killing signals are exchanged. This enforced proximity appears to boost the efficiency of cytotoxic cells, allowing them to recognize and destroy malignant cells that previously slipped past surveillance.

Coverage of the King’s College London work explains that in their latest study, laboratory experiments and animal models revealed the modified antibody activated immune cells circulating in the bloodstream and within tumors, which coincided with restricted growth of aggressive and treatment resistant breast cancers. A detailed summary of this New Antibody Restricts the Growth of Aggressive and Treatment work notes that the King’s College London discovery hinged on this dual binding design, with one arm of the antibody recognizing a protein abundant on cancer cells and the other engaging immune cells on the other side. That architecture is what allowed the antibody to both flag the tumor and mobilize an attack in a single move.

Evidence from multiple preclinical models

The King’s College London data are not emerging in isolation. Separate teams have reported complementary findings using different antibody designs against triple-negative breast cancer, strengthening the sense that this is a class effect rather than a one off fluke. In one set of preclinical studies, an antibody was shown to halt triple-negative breast cancer in animal models, with investigators emphasizing that the approach remained effective even when standard treatments failed.

In that work, surgical oncologist Nancy Klauber-DeMore, M.D., at the Medical University of South Carolina, led an effort to develop a highly targeted approach against TNBC that zeroed in on a specific antigen on tumor cells. The report on this Antibody describes how the MUSC team used preclinical models to show that their antibody could suppress tumor growth and reduce metastasis, even when the cancer had already demonstrated resistance to conventional therapies. Taken together with the King’s College London findings, these data suggest that antibodies tailored to TNBC biology can meaningfully slow or stop disease progression in controlled experimental settings.

Reprogramming the tumor’s support system

What is emerging from these studies is a picture of antibodies that do more than simply bind and block. Several of the new molecules appear to reprogram the tumor’s support system, shifting the balance of signals in the microenvironment from pro tumor to anti tumor. In the triple-negative setting, where the immune landscape is often hostile to therapy, that kind of reprogramming could be as important as direct killing of cancer cells.

The report on a Novel antibody makes this point explicitly, noting that reprogramming the cancer’s immune environment suppressed primary tumor growth and the spread of triple-negative breast cancer even in advanced disease. By altering how immune cells behave within and around the tumor, the antibody effectively stripped the cancer of its protective shield. That concept dovetails with the King’s College London strategy of activating immune cells in the bloodstream and tumor bed, and with broader efforts to turn “cold” tumors “hot” so they are more visible to the immune system.

From lab bench to patient bedside

For patients and clinicians, the obvious question is how quickly these preclinical wins can translate into real world treatments. The path from mouse to medicine is rarely straightforward, and many promising agents stumble in early human trials. Yet the antibody field has a track record of successful translation in oncology, from trastuzumab in HER2 positive breast cancer to checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma, which gives these new molecules a clearer regulatory and clinical roadmap than entirely novel drug classes.

Organizations focused on breast cancer research are already positioning antibody based strategies as a key pillar of future therapy. One major charity has highlighted how its researchers have discovered a new approach for treatment resistant breast cancers using engineered antibodies that can be combined with existing drugs to overcome resistance, describing this as a way to give patients options when standard regimens stop working. In its research news, that group details how our researchers have discovered antibody based methods that could be slotted into current treatment pathways, rather than requiring a complete overhaul of care. That kind of integration will be crucial if the King’s College London style antibodies are to move quickly into clinical testing.

How this fits into the broader breast cancer pipeline

The antibody breakthroughs are arriving in a landscape already crowded with experimental strategies for TNBC, from PARP inhibitors in BRCA mutated disease to antibody drug conjugates that deliver chemotherapy directly to tumor cells. Large research programs have cataloged dozens of ongoing trials that test new combinations of immunotherapy, targeted agents and novel biologics across the spectrum of breast cancer subtypes. Within that context, the engineered antibodies against drug resistant and triple-negative disease are part of a broader push to personalize treatment based on tumor biology rather than a one size fits all regimen.

National cancer research overviews emphasize that breast cancer studies now span everything from prevention and early detection to metastatic disease, with particular attention to aggressive subtypes like TNBC and brain metastases. A comprehensive summary of breast cancer research notes that investigators are exploring immunotherapies, targeted drugs and novel antibody formats to improve outcomes in patients whose tumors do not respond to standard hormone or HER2 directed therapies. The new antibodies that restrict growth of aggressive and treatment resistant cancers fit squarely into that agenda, offering a potential lifeline for patients who currently exhaust their options far too quickly.

Real world stakes: brain spread and advanced disease

For many patients with TNBC, the most frightening complication is not the primary tumor but where it might go next. Brain metastases are a particular concern, often appearing early in the disease course and carrying a grim prognosis. Researchers have been working to identify the genes and pathways that drive this spread, in hopes of finding targets that could be blocked before cancer cells seed the brain.

One group at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland has identified a key gene driving breast cancer spread to the brain, providing valuable insights into how tumor cells adapt to and colonize the central nervous system. Their work, published in the Opens in Journal of the National Cancer Institute, points to potential new treatment avenues for patients whose tumors are prone to brain spread. While the new antibodies discussed here have so far been tested mainly in primary and systemic disease models, the same logic of targeting specific drivers and reprogramming the immune environment could eventually be applied to prevent or treat brain metastases, especially if combined with agents that cross the blood brain barrier.

What early coverage tells patients and families

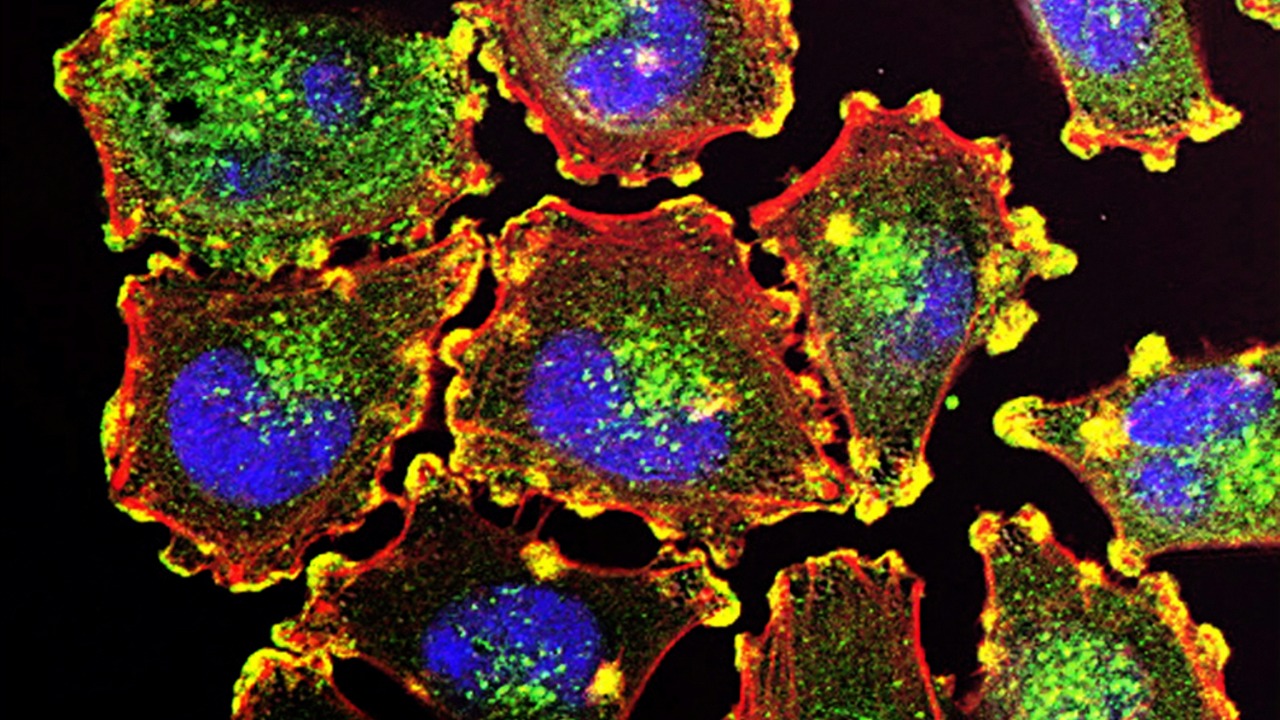

Outside the technical literature, early coverage of these antibody advances has tried to translate the science into plain language for patients and families. Reports have highlighted that a newly developed antibody can restrict the growth of aggressive breast cancers in laboratory and animal studies, framing the discovery as a promising step for people whose tumors do not respond to existing drugs. One such account, illustrated with a Photo by Thirdman via Pexels and written By Talker and By Stephen Beech, stresses that the antibody shows promise against aggressive breast cancers but still needs to be tested in people. That balance between hope and caution is essential, especially for communities that have seen too many “breakthroughs” fail to materialize in the clinic.

Another summary aimed at general readers describes how an antibody stops triple-negative breast cancer in studies, explaining that TNBC is one of the most aggressive forms of the disease and that the antibody was able to halt tumor growth in preclinical models. The piece on Antibody Stops Triple notes that while further research is needed, the findings could eventually lead to new treatment options for patients with limited choices. For families navigating a TNBC diagnosis, even the possibility of a new line of defense can change how they think about the future.

How clinicians are preparing for the next wave

Oncologists who specialize in TNBC are already accustomed to rapid shifts in the treatment landscape, from the introduction of immunotherapy to the rise of antibody drug conjugates like sacituzumab govitecan. Conference updates have chronicled how several new approaches are being tested in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, including combinations of chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted agents informed by fresh laboratory research. The emerging antibody platforms that directly engage immune cells and reprogram the tumor microenvironment are likely to be folded into this evolving mix rather than replacing existing tools outright.

One overview of TNBC treatment updates notes that Several new approaches are being tested in patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer now, with the expectation that new laboratory research will feed directly into future clinical trials. As antibodies that restrict the growth of aggressive and treatment resistant tumors move closer to first in human studies, clinicians will be watching for data on safety, durability of response and how best to sequence or combine them with existing regimens. The goal is not just to add another drug to the list, but to build rational, biology driven treatment plans that finally bend the survival curve for the deadliest breast cancers.

The cautious optimism of a genuine advance

For all the justified excitement, it is important to keep the current evidence in perspective. The antibodies that appear to stop or sharply slow triple-negative breast cancer have so far done so in controlled laboratory and animal models, not in the messy reality of human disease with its comorbidities, prior treatments and genetic diversity. Many agents that look powerful in mice falter in people, either because they are less effective or because side effects limit their use. Regulators will demand rigorous phase 1 and 2 trials before any of these molecules move into standard care.

Yet the convergence of multiple independent lines of research, from the King’s College London engineered antibodies that restrict growth of aggressive and treatment resistant tumors to the MUSC antibody that halts TNBC in preclinical models and the novel molecules that reprogram the immune environment, justifies a measure of cautious optimism. A separate report on how Oct findings showed a new antibody restricting the growth of aggressive and treatment resistant breast cancers reinforces the sense that this is not a one off observation. For patients facing triple-negative disease, the idea that a precisely engineered antibody might one day stop their cancer in its tracks is no longer science fiction. It is a hypothesis now being tested, molecule by molecule, in labs around the world.

More from MorningOverview