Ultrashort bursts of laser light are giving scientists a way to freeze one of chemistry’s most elusive moments, the instant when two molecules briefly share electrons before flying apart. By catching this fleeting “molecular handshake” in action, researchers are starting to map how electrons move in liquids on timescales so short that conventional tools might as well be standing still.

I see this as more than a technical milestone. It is a shift in how we can watch and eventually steer chemical reactions, with implications that reach from cleaner energy technologies to smarter drug design, all rooted in the ability to track electrons in motion rather than inferring their paths after the fact.

Why a “molecular handshake” matters for chemistry

Chemistry is often taught as a story of bonds forming and breaking, but the real action happens in the in‑between, when electrons are briefly shared, transferred, or rearranged. That transient contact, the molecular handshake, governs whether a reaction proceeds, stalls, or branches into an entirely different pathway, yet it has remained largely invisible because it unfolds in less than a billionth of a second. Capturing that moment directly, instead of reconstructing it from before‑and‑after snapshots, is essential if we want to understand why some reactions are efficient while others waste energy or produce unwanted byproducts.

In liquids, this challenge is even tougher, because molecules are constantly jostling, rotating, and colliding in a dense, disordered environment. The handshake between two partners can be disrupted by a third, or reshaped by the surrounding solvent, in ways that traditional spectroscopy tends to average out. By resolving the handshake itself, rather than its long‑lived aftermath, researchers can start to see how specific electron motions in a crowded liquid mixture set the stage for processes like charge transfer, catalysis, and light harvesting, which are central to technologies from solar cells to electrochemical batteries.

From ultrashort pulses to attosecond timing

To catch such a brief event, the light pulses used to probe it must be even shorter, which is where ultrashort lasers come in. These pulses compress light into bursts so brief that they can be used as a timing ruler for electron motion, allowing scientists to track changes that occur in less than a billionth of a second. In the work behind the molecular handshake result, the key was to generate and control pulses that could interrogate electrons on the same timescale as their fastest rearrangements, rather than averaging over slower nuclear motions.

That level of temporal precision pushes into the attosecond regime, where an attosecond is a billionth of a billionth of a second, and it demands both stable laser systems and clever detection schemes. By sculpting the waveform of these ultrashort pulses and synchronizing them with the dynamics inside a liquid, researchers can effectively strobe the system, watching electrons respond in real time instead of inferring their behavior from static spectra. This is what turns a laser from a blunt illumination tool into a stopwatch for quantum motion.

High-harmonic spectroscopy as a new kind of camera

Turning ultrashort pulses into a practical probe of liquids requires more than raw speed, it calls for a way to translate electron motion into a measurable signal. High‑harmonic spectroscopy does this by converting the interaction between light and matter into a comb of new frequencies, or harmonics, that encode how electrons are moving. When a strong laser field drives electrons in a medium, they can emit light at multiples of the original frequency, and the pattern of those high harmonics carries a fingerprint of the underlying dynamics.

In the experiments that revealed the handshake, a team of researchers from Ohio State University and Louisiana State University used this high‑harmonic response as a kind of camera for electron motion in liquid mixtures. By analyzing how the harmonic spectrum changed as molecules interacted, they could infer when electrons were briefly shared between partners and how that sharing evolved on timescales shorter than a billionth of a second. Instead of taking a literal picture, they reconstructed the handshake from the way the liquid reshaped the outgoing light, turning the spectrum itself into a dynamic map of electron behavior.

What the “molecular handshake” looks like in a liquid

At the heart of the new work is the realization that a handshake between molecules is not a static bond, but a rapidly shifting exchange of electron density that can be tracked through its optical signature. When two molecules in a liquid mixture approach closely enough, their electronic clouds overlap, creating a transient state where electrons are neither fully localized nor fully transferred. The high‑harmonic signal responds sensitively to this overlap, so the appearance of specific features in the spectrum marks the moment when the handshake occurs and then fades.

Using ultrafast high‑harmonic spectroscopy, the researchers were able to capture attosecond‑scale electron dynamics in these liquid mixtures, revealing that specific spectral components rise and fall in step with the handshake. The technique, described as Ultrafast high‑harmonic spectroscopy, effectively turns the liquid into its own reporter, with the emitted harmonics tracing how electrons slosh between partners during the brief instant of contact. What emerges is not a single frozen frame, but a time‑resolved sequence that shows how the handshake forms, strengthens, and then dissolves back into the fluctuating background of the liquid.

The role of LSU, Ohio State, and a broader research ecosystem

Behind the technical achievement is a collaboration that spans institutions and disciplines, reflecting how complex it is to push spectroscopy into this regime. The partnership between Ohio State University and Louisiana State University brought together expertise in ultrafast laser development, liquid‑phase chemistry, and theoretical modeling, all of which were needed to interpret the subtle signatures of the handshake. Without that combination, the high‑harmonic spectra would be rich in data but poor in meaning, since it takes careful modeling to connect specific harmonic features to particular electron motions.

Louisiana State University has been building a broader portfolio of work in advanced spectroscopy and quantum materials, and the handshake result fits into a pattern of research that leverages strong laser facilities and cross‑department collaborations. The institution’s science programs, highlighted in its research news, have increasingly focused on problems where ultrafast tools can reveal hidden dynamics, from condensed matter systems to complex fluids. By anchoring the handshake study within this ecosystem, the team could draw on both experimental infrastructure and a community of theorists and chemists ready to translate raw signals into chemical insight.

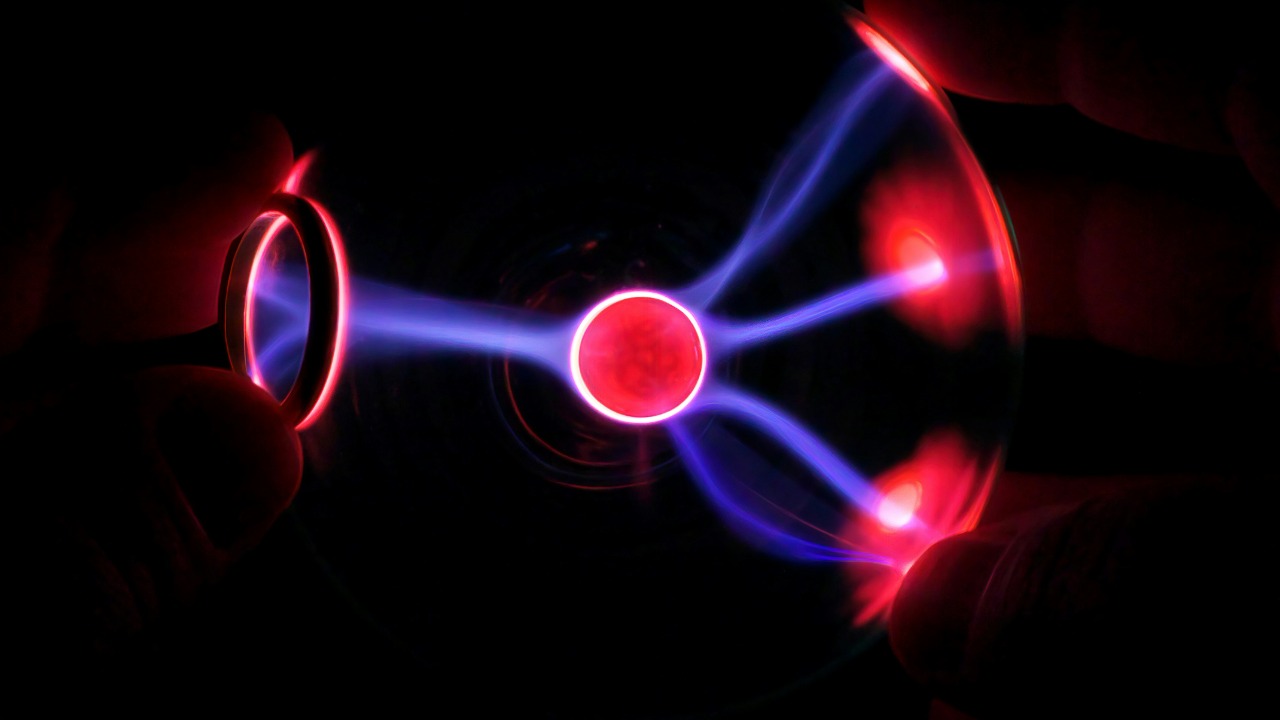

Visualizing the invisible: from artist’s impression to physical insight

Because the handshake itself is too small and too fast to see directly, visual metaphors play an important role in helping both scientists and the public grasp what is happening. An Artist’s impression of high‑harmonic emission in a liquid, for example, can depict the laser pulse as a beam that briefly locks two molecules together in a glowing bridge of light. While stylized, such imagery reflects a real physical process, in which the strong field of an ultrashort pulse distorts electron clouds and triggers the emission of harmonics that encode the handshake.

In my view, these visualizations are not just outreach tools, they are conceptual scaffolding that helps researchers reason about phenomena that cannot be directly imaged. When I picture the handshake as a luminous arc between molecules, I am really thinking about the transient redistribution of electron density that the high‑harmonic spectrum is sensitive to. The art becomes a shorthand for a complex quantum process, reminding us that behind every stylized graphic lies a carefully measured pattern of light and a set of equations that tie that pattern to the underlying electron motion.

Why attosecond liquid dynamics are a frontier

Most attosecond science to date has focused on gases or solids, where the environment is either very dilute or highly ordered, which simplifies both the experiments and the theory. Liquids sit awkwardly in between, dense enough that molecules constantly interact, but disordered enough that no two local environments are exactly alike. Probing attosecond‑scale dynamics in such a medium means dealing with a constantly shifting landscape of molecular configurations, any one of which could host a handshake with slightly different characteristics.

That is precisely why the new results are so significant. By showing that high‑harmonic spectroscopy can still extract clear signatures of electron motion from this noisy background, the researchers have opened a path to studying a wide range of liquid‑phase processes that were previously out of reach. I see this as a bridge between the clean, idealized systems of early attosecond work and the messy, real‑world environments where most chemistry actually happens, from biological membranes to industrial solvents. The handshake is a proof of concept that the attosecond toolkit can be adapted to the complexity of liquids without losing its resolving power.

Potential applications: from solar fuels to pharmaceuticals

Once you can watch electrons move in liquids on attosecond timescales, a host of practical questions become more tractable. In solar fuel research, for instance, the efficiency of a photoelectrochemical cell often hinges on how quickly and cleanly electrons can be transferred from a light‑absorbing dye to a catalyst in a liquid electrolyte. The handshake between those components determines whether the absorbed photon energy is converted into chemical fuel or lost as heat. High‑harmonic spectroscopy could reveal which molecular pairings and solvent environments promote a strong, well‑timed handshake, guiding the design of more efficient systems.

In pharmaceuticals, many key reactions occur in solution, where subtle changes in solvent composition or molecular structure can dramatically alter reaction pathways. Being able to see how electrons are shared during the critical handshake stage could help chemists understand why a particular drug precursor follows one route instead of another, or why a side reaction dominates under certain conditions. I can imagine a future in which ultrafast spectroscopic fingerprints of the handshake become a standard diagnostic tool in reaction optimization, much like chromatograms and NMR spectra are today, but with a direct window into the earliest electronic events that set the course of a synthesis.

Technical hurdles and what comes next

Despite the excitement, the technique is far from turnkey. Generating stable ultrashort pulses with the right characteristics for high‑harmonic spectroscopy in liquids requires precise control over laser intensity, pulse shape, and focusing conditions, all while avoiding damage to the sample. The liquid itself can introduce complications, such as absorption or scattering of the driving pulse, that must be carefully managed to ensure that the measured harmonics truly reflect electron dynamics rather than experimental artifacts. Each new liquid mixture or molecular system may demand its own optimization, from the choice of wavelength to the geometry of the interaction region.

On the analysis side, interpreting high‑harmonic spectra in terms of specific electron motions in a disordered liquid remains a demanding theoretical problem. It calls for models that can handle both the quantum mechanics of electrons and the statistical complexity of fluctuating molecular environments. Looking ahead, I expect progress to come from tighter integration between experiment and computation, with simulations used not just to explain observed spectra but to predict which systems will exhibit the clearest handshake signatures. As those models improve, the technique should become more predictive and less exploratory, turning the molecular handshake from a striking demonstration into a routine probe of liquid‑phase chemistry.

How this reshapes our intuition about chemical reactions

For generations, chemists have relied on energy diagrams and reaction coordinates to visualize how molecules move from reactants to products, with transition states perched atop potential energy barriers. The molecular handshake adds a new layer to that picture, emphasizing that the key step is not just climbing an energy hill, but orchestrating a precise, ultrafast exchange of electrons that may last only a few hundred attoseconds. Seeing that exchange directly forces us to think of reactions less as smooth trajectories and more as sequences of rapid, quantized events that can be probed and perhaps controlled with tailored light fields.

As I reflect on the handshake work, I find that it nudges my intuition away from static structures and toward dynamic processes, where the same pair of molecules can explore many fleeting electronic configurations before settling into a product state. High‑harmonic spectroscopy in liquids gives that intuition a concrete foundation, tying abstract ideas about electron correlation and coherence to measurable patterns of emitted light. In that sense, the snapshot of a molecular handshake is not just a technical feat, it is a conceptual pivot that encourages us to see chemistry as a choreography of electrons in time, with ultrashort laser pulses as both the spotlight and the metronome.

More from MorningOverview