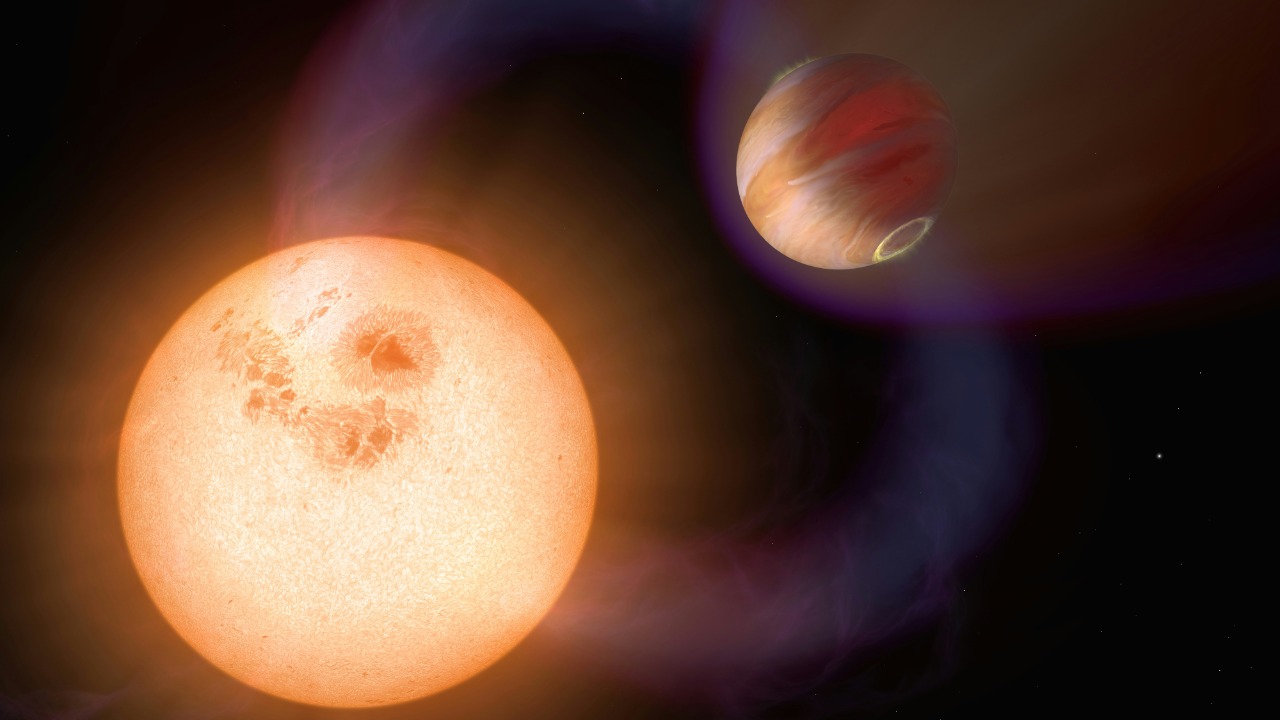

Astronomers have captured a rare and remarkably close view of a giant planet circling a pair of tightly bound suns, offering one of the clearest real-world echoes yet of the fictional world Tatooine. The discovery pushes direct imaging techniques into new territory, revealing a massive world in a configuration that was once purely the stuff of science fiction but is now a precise, measurable system in our own galaxy.

I see this planet, formally labeled HD 143811 (AB)b, as a turning point for how we study complex star systems, because it orbits two stars at a distance far smaller than any previously imaged circumbinary giant. That proximity, combined with the system’s youth and brightness, turns it into a natural laboratory for testing how planets form and survive in the gravitational crossfire of twin suns.

Why this circumbinary giant is such a breakthrough

The core of the story is simple but profound: Astronomers have directly imaged a giant exoplanet that orbits a close pair of stars at a distance that beats previous records by a wide margin. Instead of circling a single sun like Jupiter or Saturn, HD 143811 (AB)b loops around two stars that themselves are locked in a tight embrace, creating a gravitational environment that is far more chaotic than our own Solar System. Directly resolving a planet in that setting is technically demanding, which is why this object immediately stands out as a landmark detection.

According to Astronomers who analyzed the system, the planet orbits its binary hosts several times closer than comparable directly imaged circumbinary giants that have been found so far. That means the planet is not just another distant dot on the outskirts of a wide stellar pair, but a world embedded deep in the gravitational well of its twin suns. The configuration gives researchers a rare chance to test how stable such orbits can be and how early in a system’s life a massive planet can carve out a safe path around two stars at once.

A real-life Tatooine, but far more extreme

Popular culture gives me a convenient shorthand for this system: it is a real-life analogue of Tatooine, the desert world with double sunsets in Star Wars. The resemblance is not just poetic. HD 143811 (AB)b is a circumbinary planet, meaning it orbits both stars together, so any observer on its surface would see two suns rising and setting in the sky. That visual echoes Luke Skywalker’s iconic horizon, but the physics here are even more dramatic, because the stars are tightly bound and the planet is a giant, not a rocky world.

Reporting on the discovery notes that the young planet, dubbed “HD 143811 (AB)b,” is a gas giant that weighs in at roughly six times the size of Jupiter, which makes it far more massive than any terrestrial Tatooine lookalike fans might imagine. Its bulk and wide orbit would likely produce spectacular double sunrises and sunsets, but also intense radiation and dynamic weather patterns that are inhospitable to life as we know it. The sheer scale of the planet, combined with its twin-star backdrop, turns the system into a vivid demonstration that nature can assemble even more extreme versions of our favorite fictional worlds.

How Dec data and old images revealed a hidden world

One of the most striking aspects of this discovery is that the planet was hiding in plain sight. The system was observed years ago with high-end instruments, but the planet’s signal was buried in the noise until new processing techniques were applied. Only when researchers revisited the decade old Gemini data with fresh algorithms did the faint glow of HD 143811 (AB)b emerge from the glare of its twin suns, underscoring how much science still sits latent in archival observations.

In coverage of the work, Dec reports describe how the team combed through older datasets and used improved image processing to isolate the planet’s light from the surrounding starlight. That approach turned what had been a routine observation into a discovery of the closest directly imaged circumbinary giant yet. It is a reminder that as algorithms advance, astronomers can effectively reobserve the sky without pointing a single new telescope, extracting planets that were previously invisible in the data.

The people and institutions behind the find

Behind the technical achievement is a network of researchers and institutions that have been steadily pushing the limits of exoplanet imaging. At the center of this particular effort is Nathalie Jones, identified as the CIERA Board of Visitors Graduate Fellow at Weinberg and a member of Wang’s research group. Her role highlights how graduate-level researchers are often the ones who dive deepest into the data, refine the algorithms, and spot the subtle signatures that more automated pipelines might miss.

Reports credit Nathalie Jones in her capacity as a CIERA Board of Visitors Graduate Fellow at Weinberg and as part of Wang’s team with leading the analysis that pulled HD 143811 (AB)b out of the archival observations. That institutional backing, from CIERA to the broader university environment, provided the computational resources and mentorship needed to tackle such a complex problem. It is a case study in how sustained investment in early career scientists and specialized centers can pay off with discoveries that reshape our understanding of planetary systems.

What makes this planet “closest” among its peers

Calling HD 143811 (AB)b the closest giant planet ever seen orbiting binary stars is not about its distance from Earth, but about how snugly it orbits its twin suns compared with other directly imaged circumbinary giants. Previous systems have tended to feature planets on very wide orbits, where the gravitational tug of the two stars averages out and stability is easier to maintain. In this case, the planet is tucked much nearer to the binary, where the gravitational field is more variable and the orbital dynamics are more delicate.

According to Astronomers who characterized the system, HD 143811 (AB)b orbits several times closer to its host stars than other directly imaged planets around binary stars. That tighter configuration makes it a crucial benchmark for testing models of orbital stability and migration in circumbinary systems. By comparing its orbit to the theoretical “safe zones” predicted by simulations, researchers can refine their understanding of where planets can survive long term in the complex gravitational environment created by two suns.

A massive, glowing world powered by formation heat

Beyond its orbit, the physical nature of HD 143811 (AB)b is equally revealing. As a young gas giant roughly six times the size of Jupiter, it is still radiating significant heat from its formation, which makes it brighter in infrared wavelengths than an older, cooler planet would be. That residual glow is precisely what allows direct imaging instruments to pick it out against the glare of its host stars, turning the planet’s youth into an observational advantage.

Researchers note that the planet’s brightness is driven by light from retained formation heat, which is still leaking out of its deep atmosphere. That glow provides a direct window into the planet’s temperature and structure, offering clues about how quickly such massive worlds cool and contract over time. By comparing HD 143811 (AB)b’s luminosity to models of gas giant evolution, astronomers can estimate its age and formation history, tying its current state back to the early stages of the circumbinary disk that gave birth to it.

Two suns, tight orbits, and a fast stellar dance

The host stars themselves are as important to the story as the planet that orbits them. They form a tight binary, revolving around one another in a matter of days rather than years, which creates a rapidly changing gravitational field at the location of the planet. That fast stellar dance shapes the region where stable orbits are possible, carving out zones where a planet like HD 143811 (AB)b can survive and regions where any smaller bodies would be quickly ejected or destroyed.

Coverage of the system notes that the stars tightly revolve around one another, taking just 18 Earth days to complete one revolution. That rapid orbit means the gravitational center of the system is constantly shifting, yet HD 143811 (AB)b manages to maintain a stable path around both stars. The configuration provides a natural experiment in celestial mechanics, allowing scientists to test how planetary orbits respond to a moving central mass and to refine predictions about where other circumbinary planets might be hiding.

How rare are planets like this in the galaxy

From a statistical perspective, HD 143811 (AB)b occupies a rare niche. Binary stars are common in the Milky Way, but only a fraction of known exoplanets orbit such pairs, and an even smaller subset have been directly imaged. Most circumbinary planets have been found through transit methods, where the planet passes in front of the combined light of the two stars, rather than through direct detection of the planet’s own glow. That makes each directly imaged circumbinary giant a valuable outlier that can anchor theoretical models.

Reporting on the broader population notes that while a large share of stars in our galaxy are in multiple systems, only a small fraction of known exoplanets orbit binaries, and an even smaller number have been captured in images like this one. The discovery of HD 143811 (AB)b, described as a rare exoplanet orbiting two suns, underscores how unusual it is to find a massive world in such a tight circumbinary orbit. It suggests that while nature can build these systems, they may require specific conditions in the protoplanetary disk and binary configuration, which in turn helps refine where future surveys should focus their searches.

Distance from Earth and what we can learn from afar

Even though HD 143811 (AB)b is the closest giant planet to its own twin stars among directly imaged circumbinary systems, it still sits far from us in absolute terms. The planet is located some 446 light-years away from Earth, which places it well outside our local stellar neighborhood but still close enough for detailed follow-up with current and upcoming telescopes. That distance is a reminder that even relatively nearby systems can host exotic architectures that differ dramatically from our own.

One report notes that the planet, Dubbed HD 143811 AB b, is a gas giant located some 446 light-years away from Earth in a system where the stars and planet interact in complex ways. That combination of moderate distance and extreme configuration makes it an ideal target for instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope and future ground-based observatories, which can probe its atmosphere, refine its orbit, and search for additional, smaller companions that might be lurking in the same circumbinary disk.

What this discovery means for future planet hunts

For me, the most important implication of HD 143811 (AB)b is methodological. The planet was not found by scanning a brand new patch of sky, but by reexamining existing data with sharper tools and a clearer sense of what to look for. That strategy can be replicated across other archives, potentially revealing a hidden population of circumbinary giants that were missed the first time around. Each new detection would help fill in the statistical picture of how common such systems are and how their architectures vary.

Reports on the discovery emphasize that the same techniques used to isolate HD 143811 (AB)b can be applied to other datasets to improve the detection of any other missed objects, especially in complex environments like binary systems. By combining those reprocessed images with targeted new observations, astronomers can systematically expand the catalog of directly imaged planets around multiple stars. In that sense, this closest giant planet orbiting binary stars is not just a singular curiosity, but a proof of concept for a new phase of exoplanet exploration that treats old data as fertile ground for fresh discoveries.

More from MorningOverview