For anyone trying to make sense of the climate right now, the oceans can look like a contradiction in motion. Global records show seas absorbing extraordinary amounts of heat, yet new research also points to pockets of rapid surface cooling that some voices online are already spinning into a story about looming global chill. The real picture is more complicated and, if anything, more alarming than a simple switch from warming to cooling.

What I see instead is an ocean system acting as both buffer and amplifier, soaking up excess energy while redistributing it in ways that can briefly cool some regions even as the planet as a whole heats up. Those short term dips are now being miscast as evidence that the oceans are somehow reversing global warming, when the underlying data and expert analysis point to a climate system still dominated by rising greenhouse gas concentrations, not a surprise turn toward global cooling.

Why a “cooling ocean” headline is so misleading

The idea that the seas might be speeding a new era of global cooling is seductive because it promises an escape hatch from hard choices, but it rests on a misunderstanding of how the climate system works. When I look at the balance of evidence, the oceans are still gaining heat overall, and that long term trend is what drives sea level rise, stronger storms and shifting rainfall, even if some surface patches cool for a season or two.

Short term drops in sea surface temperature are real, but they sit on top of a background of steady energy gain that has been measured across depth profiles, satellite records and ocean buoys. That is why climate researchers keep stressing that a few cooler months in one basin do not overturn decades of data on rising ocean heat content or the physics of greenhouse gases trapping energy in the Earth system.

What the global heat record actually shows

To understand whether the oceans could be ushering in a cooler planet, I start with the global numbers, and they point in the opposite direction. A recent assessment from New UNESCO finds that the rate of ocean warming has doubled in the past two decades, a sign that the seas are absorbing more of the excess heat trapped by human emissions rather than shedding it back to space. That same analysis reports that the rate of sea level rise has also doubled over roughly thirty years, a direct consequence of both thermal expansion and melting land ice.

Another section of the Jul report notes that sea level has climbed by about 9 cm over the past 30 years, a figure that is hard to reconcile with any narrative of a cooling planet. Those centimeters translate into more frequent coastal flooding, saltwater intrusion into freshwater systems and higher baseline water levels that allow storm surges to reach farther inland. When I weigh those global indicators against a few localized cooling events, the balance is clear: the oceans are still acting as a massive heat reservoir, not a brake on global warming.

The physics of a heat sponge, not a refrigerator

The basic physics of seawater make it an unlikely engine for rapid planetary cooling. As Water has a high heat capacity, it can store far more energy than air for the same temperature change, which means the ocean warms more slowly but also releases heat more gradually. That is why climate scientists treat the marine record as a more stable indicator of long term change than the more volatile air temperatures we feel day to day.

From my perspective, this high heat capacity turns the ocean into a long fuse on the climate system, delaying some impacts while locking in others. Once that energy is in the water column, it continues to influence weather patterns, ice melt and sea level for decades, even if surface readings in one region dip for a season. The idea that such a system could suddenly flip into a global cooling mode without a corresponding drop in greenhouse gas concentrations is not supported by the physics or by the observational record.

How regional cooling fits into a warming world

Where the confusion often starts is with real, dramatic cooling in specific ocean regions that are then misread as a global signal. In the equatorial Atlantic, for example, Jul research describes a pattern of record surface heat followed by rapid cooling linked to shifts in winds and currents. That study highlights how changes in the timing and strength of this oscillation can disrupt regional weather, affecting infrastructure, agriculture and water resources across nearby countries.

Farther north, scientists have documented a patch of the Atlantic that is cooling at record speed, with surface temperatures about 0.5°C below the long term average. If that anomaly persists for at least another month, it will officially be classified as an “Atla” event, a label that reflects its persistence rather than any claim that global warming has reversed. When I look at these cases together, they read as signs of a complex, shifting circulation pattern within an overall warming ocean, not as evidence that the climate system has thrown itself into reverse.

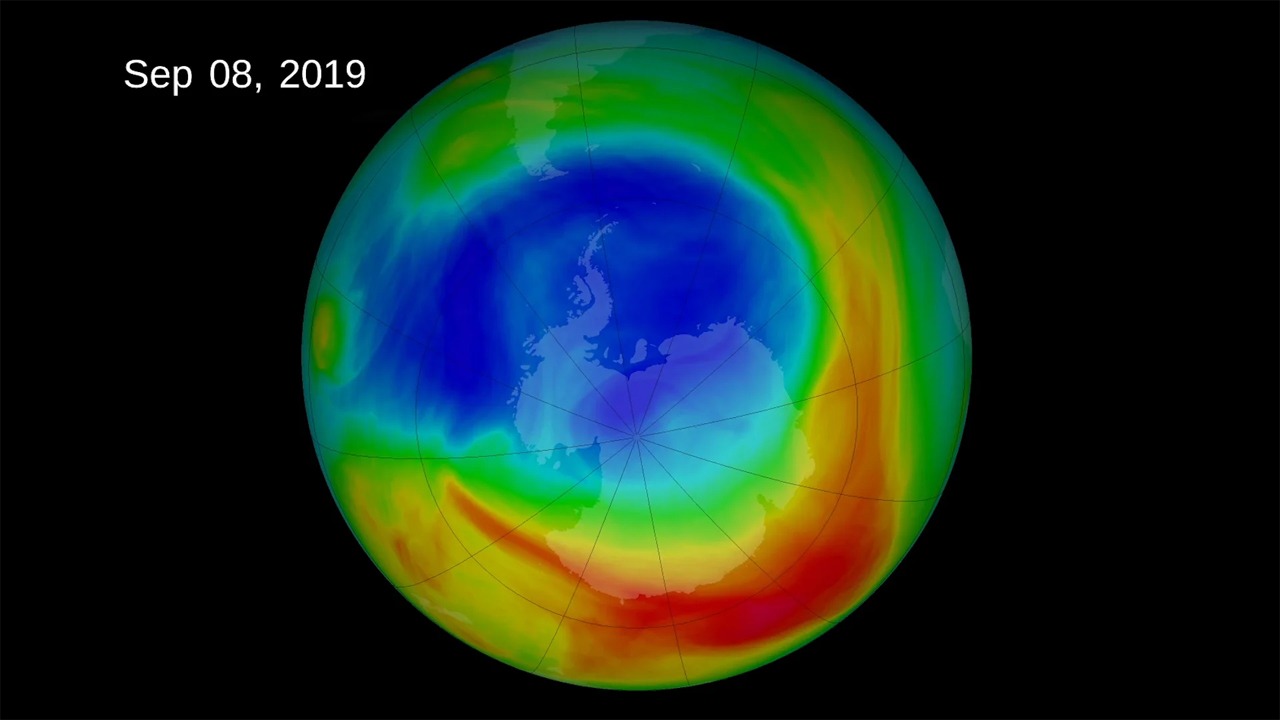

Southern Ocean surprises and what they really mean

One of the most striking examples of regional cooling comes from the waters encircling Antarctica, where researchers have found that Surface waters in the Southern Ocean have been cooling in recent decades. That trend runs counter to what many climate models had projected, and the study attributes it to a combination of melting ice and increased rainfall that freshen the upper ocean and alter how heat is mixed downward.

For me, the key point is that this Southern Ocean cooling is still framed as a response to human driven climate change, not a refutation of it. The same analysis emphasizes that the Southern Ocean is absorbing vast amounts of heat and carbon, even as its surface cools, which can have knock on effects for global circulation and ice sheet stability. In other words, a cooler surface there does not mean the planet is cooling, it means the climate system is redistributing the extra energy in ways that models are still catching up to.

Fact checks on viral “cooling proves hoax” claims

Whenever a chart of falling sea surface temperatures goes viral, I see a familiar pattern: a narrow slice of data is pulled out of context and used to claim that global warming is a “lie.” One widely shared post pointed to a short term dip in the Atlantic Ocean and declared that climate change had been debunked, but climate scientists reviewing the same data explained that the change was consistent with natural variability layered on top of a long term warming trend driven by rising greenhouse gas concentrations.

A separate review of claims about equatorial Atlantic cooling reached a similar conclusion, noting that The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration data did show record speed drops in some surface readings but that using those numbers to argue that the effects of climate change are inaccurate misrepresents what the measurements actually mean. The agency, often referred to as NOAA, stressed that the Atlantic is still warmer than in the pre industrial era and that the broader pattern of warming oceans remains intact. When I weigh those expert assessments against social media posts, the gap between evidence and rhetoric is stark.

Why a warming ocean can still feel colder in some places

Part of the confusion comes from the way people experience climate change locally. A fisherman in a patch of cooler water or a coastal community enjoying a milder summer can understandably question global averages, yet the underlying ocean record shows a system that is storing more heat even as currents and winds shuffle that energy around. The Earth system perspective is that the ocean, Covering 70 percent of the planet, acts as a vast integrator of these changes, smoothing out some extremes while amplifying others.

From that vantage point, it is entirely consistent to see local cooling episodes alongside more frequent marine heatwaves, stronger storms and rising seas. The same analysis of ocean warming notes that the amount of heat absorbed by the upper layers is even higher than previously estimated, which helps explain why weather patterns are becoming more volatile. When I connect those dots, the message is not that the oceans are cooling the planet, but that they are redistributing a growing surplus of heat in ways that can feel contradictory on the ground.

Weather extremes as the real signal

If the oceans were truly steering the planet toward a cooler state, we would expect to see a broad easing of climate impacts, yet the opposite is happening. As sea surface temperatures climb, Low lying, densely populated areas are flooding more often than they used to, and experts warn that this trend is going to get worse as higher baseline seas combine with storm surges. Warmer waters also feed more intense hurricanes and typhoons, setting up what one researcher described as an epic hurricane tug of war between competing climate influences.

In my view, these impacts are the clearest signal of what the oceans are doing with the extra heat they absorb. Rather than quietly bleeding energy back into space and cooling the planet, they are destabilising weather and climate, shifting rainfall belts, and supercharging extremes that hit communities and infrastructure. When I put the pieces together, the story that emerges is not of oceans rescuing us from global warming, but of a marine system that is already locked into amplifying its consequences.

How I read the “cooling” narrative from here

Looking across the data, I see a pattern that is both scientifically coherent and politically fraught. Scientifically, the combination of global heat gain, regional anomalies like the “Atla” event, and unexpected trends in places like the Southern Ocean all fit within a framework of a warming world with complex internal variability. Politically, those same anomalies are being cherry picked to argue that climate action is unnecessary, even as the underlying indicators, from sea level to storm intensity, keep moving in the wrong direction.

As a reporter, I find it more honest to acknowledge the surprises, such as the Mar findings on Southern Ocean cooling or the rapid shifts in the equatorial Atlantic, while keeping them anchored to the broader context of rising greenhouse gas concentrations. The weight of evidence from Jul global assessments, detailed ocean heat studies and independent checks by agencies like NOAA all point in the same direction: the oceans are not bailing us out of climate change, they are buying us time at a cost that is already showing up in flooded streets, shifting fisheries and more volatile weather.

More from MorningOverview