Nearly four decades after Voyager 2 skimmed past Uranus, a fresh look at its measurements is reshaping what scientists thought they knew about the ice giant’s strange magnetic environment. By rechecking data that had puzzled researchers since 1986, planetary scientists now argue that the spacecraft may have flown through an unusually violent blast of solar activity rather than a “typical” Uranian system.

That reinterpretation does more than tidy up an old puzzle. It suggests Uranus might behave far more like Earth during extreme space weather than anyone expected, and it strengthens the case for sending a dedicated mission to a world that has been visited only once, briefly, in the age of cassette tapes and cathode‑ray televisions.

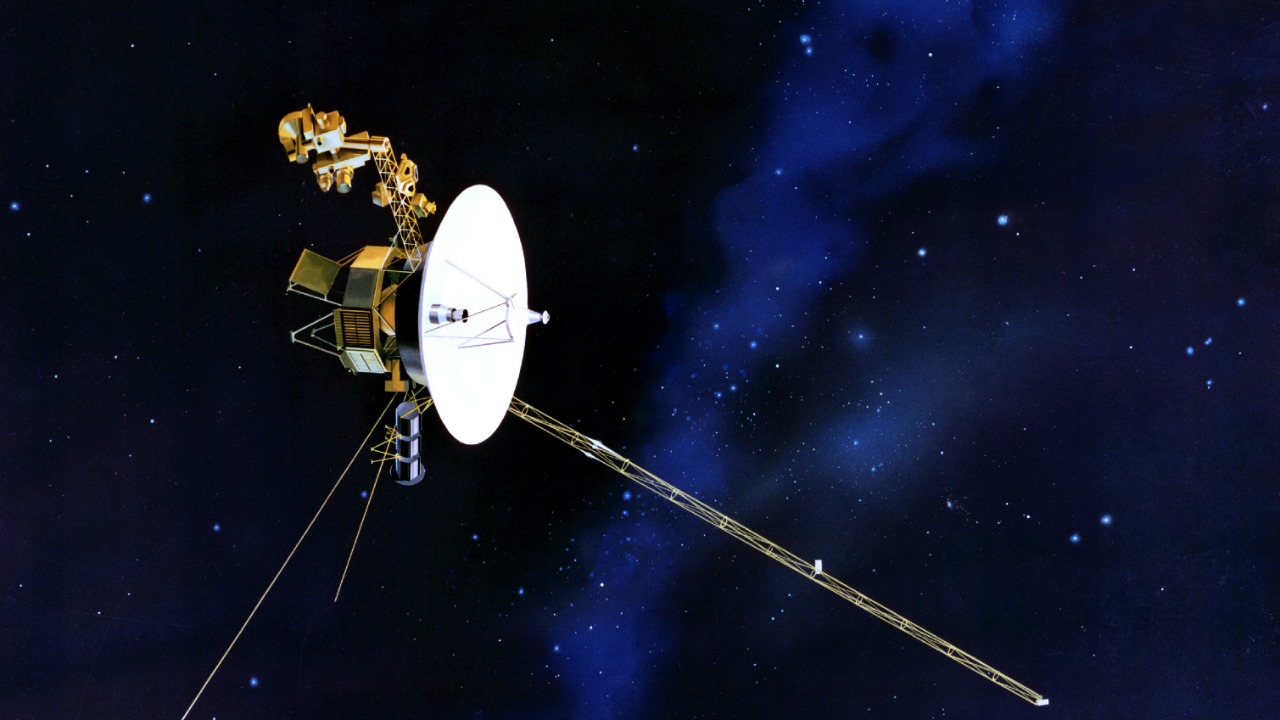

Voyager 2’s brief encounter and the mystery it left behind

When Voyager 2 swept past Uranus in the mid‑1980s, it delivered humanity’s only close‑up look at the pale, tilted planet and its retinue of moons and rings. The flyby lasted just hours, yet it produced a trove of magnetic and particle data that immediately looked odd, with radiation belts that seemed strangely weak and a magnetosphere that did not match expectations for a giant planet bathed in the solar wind. Those anomalies seeded a 39‑year debate over whether Uranus itself was fundamentally unusual or whether the spacecraft had simply arrived at a bad time.

Researchers now argue that the second scenario is far more likely, based on a detailed reanalysis of the original magnetic field and plasma measurements. By reconstructing the geometry of the encounter and comparing the readings with modern models of solar activity, they show that Voyager 2 probably crossed Uranus while a rare, highly compressed stream of solar particles was hammering the planet, distorting its magnetic bubble and skewing the readings that once defined Uranus in textbooks, a conclusion that is laid out in a peer‑reviewed Nature study.

How a “New Look” at old numbers cracked the puzzle

The breakthrough did not come from new hardware in deep space but from new ways of interrogating data that had been sitting on servers and tapes for decades. Scientists applied a “New Look” style of analysis that combined updated magnetospheric models with refined numerical tools, effectively replaying the flyby frame by frame to see how the spacecraft’s trajectory intersected the planet’s warped magnetic field. This approach allowed them to separate what belonged to Uranus itself from what was being imposed by the Sun at that moment.

In practical terms, that meant revisiting the original Voyager 2 magnetometer and charged‑particle records with modern algorithms that can track subtle changes in field direction and particle energy. The team behind this work describes how their analysis squeezed new structure out of the old signal, much like enhancing a faded photograph until hidden details emerge. By doing so, they could test whether a transient blast of solar wind could reproduce the spacecraft’s “bizarre” readings, and the match turned out to be striking.

Extreme space weather at Uranus, not a broken planet

The reinterpreted data point to a scenario in which Uranus was being pummeled by an unusually strong solar wind stream as Voyager 2 arrived, a kind of space‑weather event that can radically compress a planet’s magnetic shield. Under those conditions, magnetospheres that normally look stable and symmetric can be squeezed, twisted, and flooded with energetic particles, producing signatures that would seem inexplicable if scientists assumed a calm environment. The new work argues that this is exactly what happened, turning a one‑off storm into a decades‑long scientific headache.

That conclusion is reinforced by modeling that shows how such a compressed magnetosphere could account for the unexpectedly low ion radiation belt intensities and the peculiar distribution of electrons that Voyager 2 recorded. One study describes how “New investigations” into the flyby now frame the readings as evidence of Extreme Space Weather at Uranus, rather than a fundamentally broken or missing radiation belt system, which in turn reshapes how scientists think about the planet’s long‑term interaction with the solar wind.

Radiation belts that were hiding in plain sight

One of the longest‑standing puzzles from the flyby involved the planet’s radiation belts, the doughnut‑shaped zones of trapped charged particles that circle many planets. Voyager 2’s instruments suggested that Uranus had weaker ion belts than expected, which clashed with theories that predicted a robust, Jupiter‑like system around such a large world. For years, that discrepancy was taken as evidence that Uranus was simply an outlier, perhaps because of its extreme axial tilt or unusual interior.

The new interpretation flips that narrative by showing that the belts may have been temporarily suppressed or reshaped by the solar storm, while the electron belts were actually more intense than early analyses appreciated. One report notes that “While the ion radiation belt intensity was below expectations, the electron belt intensities were significantly higher,” a pattern that fits a scenario in which a powerful gust of solar wind was compressing the magnetosphere during Voyager 2’s passage. In other words, the belts were not missing; they were being actively sculpted by space weather at the exact moment humanity happened to look.

A rare solar event that fooled a generation

To understand why the misinterpretation lasted so long, it helps to appreciate just how unusual the solar conditions appear to have been. The reanalysis indicates that Voyager 2 likely encountered a rare configuration of the solar wind, possibly a compressed high‑speed stream or related structure, that only affects Uranus a small fraction of the time. Under that kind of onslaught, the planet’s magnetosphere would have been squeezed far closer to the planet than normal, altering the spacecraft’s path through the system and the signals it recorded.

One detailed reconstruction shows that the “second panel” of the reprocessed data reveals an unusual kind of solar weather that would only be expected about 0.4% of the time, a statistical sliver that helps explain why it took so long to recognize what was going on. By mining old Voyager 2 records, scientists now argue that the spacecraft happened to catch Uranus during this rare configuration, a conclusion that is spelled out in a technical analysis of the solar wind that accompanied the flyby.

Revisiting Voyager with new techniques and fresh eyes

The Uranus rethink is part of a broader trend in planetary science, in which researchers are returning to archival spacecraft data armed with more powerful computers and more sophisticated theory. In this case, teams explicitly set out to test whether the long‑standing anomalies could be resolved by “Revisiting old data with new analytical techniques,” rather than assuming that the planet itself had to be exotic. That mindset shift turned the Voyager 2 archive into a kind of natural laboratory for stress‑testing models of magnetospheres under extreme conditions.

Those efforts highlight how much information can still be extracted from a single flyby when the right tools are applied. By combining updated solar wind reconstructions, improved particle transport models, and careful error analysis, scientists have been able to build a far more accurate picture of Uranus than was possible in the 1980s. One account emphasizes that Revisiting old data with new technique has not only clarified past misunderstandings but also underscored the importance of timing in planetary flybys, since a few hours of atypical conditions can skew perceptions for decades.

Magnetospheres, “Magnetospheres,” and what Uranus shares with Earth

At the heart of the new picture is a better understanding of magnetospheres, the invisible magnetic bubbles that surround planets and shield them from the solar wind. On Earth, the magnetosphere deflects most charged particles, but it can be dramatically compressed during strong solar storms, driving auroras and sometimes disrupting power grids. The reinterpreted Voyager 2 data suggest that Uranus experiences analogous episodes, with its own magnetosphere being squeezed and reshaped when a potent stream of solar particles slams into it.

One detailed account of the flyby notes that “Magnetospheres shield planets from solar storms and wind, but become compressed by this potent stream of solar particles,” a description that now appears to apply to Uranus as clearly as it does to Earth. The same report explains how such compression can turn the magnetosphere into an obvious source of radiation, a pattern that helps reconcile the spacecraft’s puzzling readings with modern theory. By framing Uranus within this broader family of Magnetospheres, scientists can now compare its behavior more directly with Earth’s, Jupiter’s, and Saturn’s, rather than treating it as an outlier.

Uranus may have more in common with Earth than its color suggests

One of the most intriguing implications of the reanalysis is that Uranus may not be as alien, magnetically speaking, as its distant orbit and icy composition might imply. The updated models indicate that the planet’s magnetic field can trap and accelerate charged particles in ways that echo Earth’s Van Allen belts, especially during periods of heightened solar activity. That similarity matters because it hints that the physics governing planetary radiation environments may be more universal than the old Uranus data suggested.

Recent work based on “40-year-old” Voyager 2 probe data argues that Uranus may have more in common with Earth than previously thought, particularly in how both planets respond to particles carried on the solar wind. One report on Uranus, Earth, Voyager, News, By Keith Coope emphasizes that the same basic processes that shape Earth’s space weather appear to be at work around the ice giant, even if the geometry and intensity differ. That realization reframes Uranus as a valuable comparative laboratory for understanding how magnetospheres operate across the Solar System.

From “weird outlier” to member of a larger family of tilted worlds

For years, Uranus was portrayed as the oddball of the outer Solar System, with its 98‑degree axial tilt, sideways rotation, and lopsided magnetic field. The new interpretation of the Voyager 2 data does not erase those quirks, but it does suggest that the planet’s magnetospheric behavior may not be uniquely strange. Instead, it may share key traits with other worlds that have misaligned fields or unusual tilts, including Neptune and possibly some exoplanets orbiting distant stars.

One recent analysis argues that Uranus may have more in common with Earth than we thought and notes that Uranus is not alone in having a strange magnetic field, pointing out that Neptune’s is similarly misaligned. In that context, planetary scientist Uranus, Allen is quoted as saying that “This is just one more reason to send a mission targeting Uranus,” and adds that perhaps misaligned magnetospheres are typical rather than exceptional. That perspective turns Uranus from a curiosity into a key test case for understanding a whole class of planets.

Why timing matters when you only get one flyby

The Voyager 2 recheck also serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of drawing sweeping conclusions from a single, time‑limited encounter. Because the spacecraft spent only a short window inside Uranus’s magnetosphere, any transient event during that period could dominate the data set, as appears to have happened with the rare solar wind configuration now identified. In effect, scientists spent decades trying to generalize from what may have been an extreme, short‑lived episode rather than a representative snapshot.

Several accounts of the new work stress that timing is everything when it comes to interpreting flyby data, especially for dynamic systems like magnetospheres that can change dramatically over hours or days. One report on Rare space events notes that a “New analysis of data from NASA’s” Voyager 2 shows how a single unusual configuration can make researchers “think all the wrong things” about a planet if they assume it is typical. That lesson is now feeding into the design of future missions, which aim for longer orbital campaigns that can capture a full range of conditions rather than a single snapshot.

The case for a dedicated Uranus mission grows stronger

As the reinterpreted Voyager 2 data recast Uranus as both less mysterious and more scientifically valuable, momentum is building for a new mission that would orbit the planet and study it in depth. Planetary scientists argue that only a long‑lived spacecraft can map how the magnetosphere responds across an entire Uranian year, track changes in the radiation belts, and watch how the solar wind sculpts the system over time. The recent findings effectively turn the old flyby into a teaser trailer for a much richer story that has yet to be told.

Advocates point out that Uranus offers a unique combination of features, from its tilted spin axis to its icy interior and complex magnetic field, that make it an ideal target for understanding how planets form and evolve. One report on Uranus mysteries solved with Voyager data underscores how much insight was extracted from a single pass and argues that a dedicated orbiter could transform that glimpse into a comprehensive portrait. In that sense, the Voyager 2 recheck is not just about solving an old puzzle; it is about sharpening the scientific questions that a future mission will be built to answer.

Old spacecraft, new era of planetary science

The Uranus story captures a broader shift in how scientists treat legacy missions. Rather than viewing Voyager 2 as a relic of a bygone era, researchers are treating its archive as a living resource that can be reinterpreted as theory and technology advance. That mindset has already paid dividends at other worlds, from Saturn’s rings to Jupiter’s auroras, and Uranus is now joining that list as a beneficiary of twenty‑first‑century analysis applied to twentieth‑century measurements.

In parallel, public‑facing explainers have helped translate the technical findings into accessible narratives, showing how a spacecraft launched in the 1970s can still reshape planetary science today. One such piece on Home, Science, Space, Voyager, Uranus walks through how the flyby was “packed with surprises” and how the new interpretation finally makes sense of them. Together with the technical literature, these accounts mark the moment when a 39‑year‑old mystery stops being a nagging anomaly and becomes a cornerstone of a more coherent story about how planets, including our own, live within the changing moods of their star.

More from MorningOverview