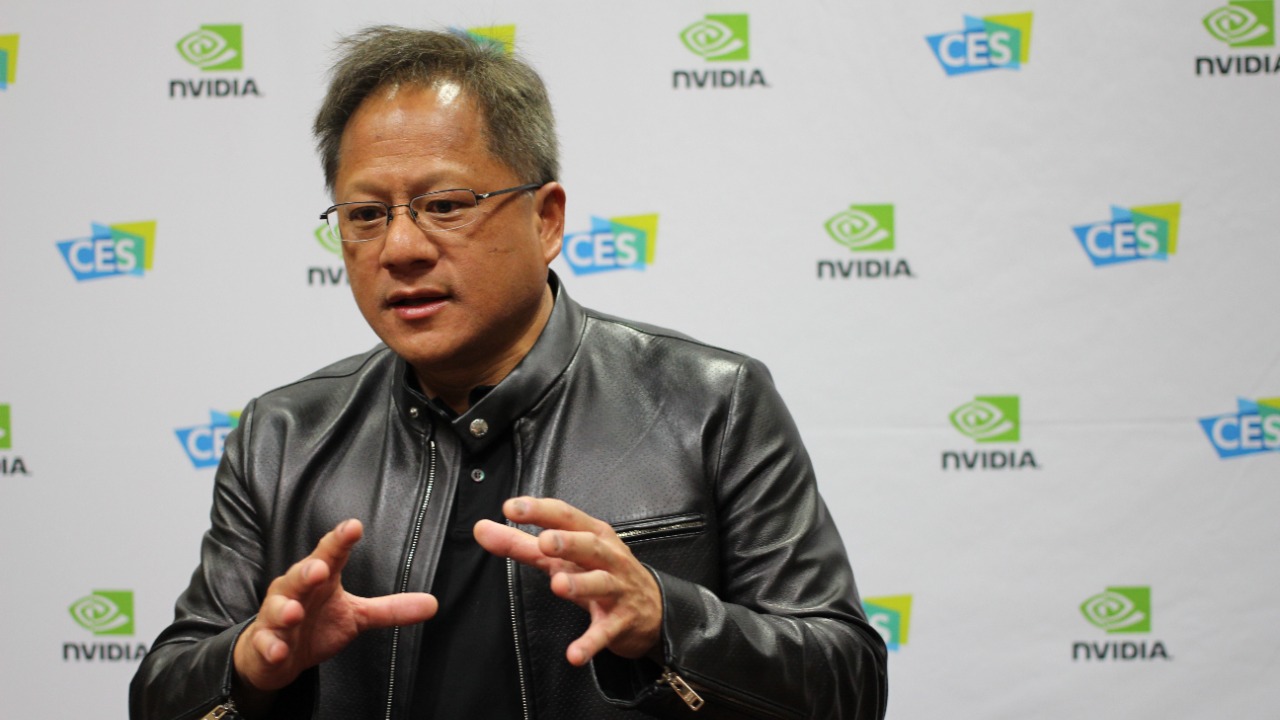

Artificial intelligence has become the villain of choice in energy debates, blamed for everything from looming blackouts to derailed climate goals. Yet the person selling more AI chips than anyone else, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, is arguing that the story is far more nuanced than a simple tale of runaway power demand. Instead of treating AI data centers as an existential threat to the grid, he is positioning them as a catalyst for cleaner infrastructure, more efficient computing and a faster buildout of low carbon power.

That stance puts Huang at the center of a high stakes argument about how much electricity AI will really consume, who should pay for the upgrades and whether the technology ultimately accelerates or slows decarbonization. His message is blunt: the world will need huge amounts of electricity, but the answer is not panic, it is smarter chips, accelerated computing and a massive expansion of nuclear and other firm clean power.

Huang’s pushback against the AI power scare

When Nvidia’s market value and influence exploded on the back of generative AI, critics quickly warned that the company’s chips were driving an unsustainable surge in electricity use. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has responded by arguing that the narrative is backward, insisting that accelerated computing can actually cut the energy required for a given amount of work compared with traditional servers. In his telling, the real shift is not that AI suddenly invented power hungry computing, but that it exposed how inefficient general purpose architectures have been for the past decade.

Huang has framed this as a structural change in how data centers are built, saying that Nvidia (NVDA) is replacing sprawling racks of CPUs with tightly integrated systems that deliver more performance per watt. In recent remarks, he has described how Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang sees AI clusters as a way to consolidate workloads that used to be scattered across thousands of less efficient machines, a point he has tied directly to accelerated computing in the past decade. That argument underpins his broader effort to cool the rhetoric around AI’s power appetite, by shifting attention from raw megawatts to the energy intensity of each unit of computation.

From “power hog” to efficiency engine

Huang’s core claim is that the industry has been measuring the wrong thing. Instead of fixating on the total electricity drawn by AI data centers, he wants policymakers and investors to look at how much useful work those facilities deliver per kilowatt hour. He has repeatedly contrasted generative AI running on Nvidia systems with legacy CPU farms, arguing that the former can complete the same tasks with far fewer servers and lower overall energy use, even if each rack is more densely powered.

That logic is central to how Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang talks about the economics of AI infrastructure, where he links the company’s GPUs, networking gear and software into full stack systems that enable what he calls better systems that enable AI economics. By his account, the shift to accelerated computing is not just about speed, it is about reducing the energy consumed per query, per model training run and per enterprise workload. That is why he has been so dismissive of blanket claims that AI is inherently a power hog, arguing instead that the technology is forcing a long overdue upgrade of the world’s digital infrastructure.

AI as a driver of grid decarbonization

Huang is not only defending AI’s energy use, he is also casting it as a tool for cleaning up the grid itself. He has argued that Artificial intelligence can help utilities manage variable renewables, forecast demand more accurately and optimize transmission flows, which in turn makes it easier to integrate large amounts of wind and solar. In his view, the same algorithms that power chatbots and image generators can also orchestrate a more flexible, resilient electricity system.

That optimism extends to the physical footprint of data centers. Huang has said that NVIDIA, under his leadership as CEO, is working with power providers to site AI facilities where they can soak up surplus clean generation and provide flexible load that ramps down when the grid is stressed. He has linked this directly to the idea that AI will help, not hinder, grid decarbonization, arguing that smarter software and better planning can turn data centers into partners for utilities rather than adversaries, a point he has underscored in detailed comments on grid decarbonization.

Why nuclear power sits at the center of Nvidia’s vision

Even as he talks up efficiency, Huang is blunt that AI will still require a vast expansion of generation capacity. The twist is that he sees that expansion as an opportunity to lock in low carbon power for decades, rather than doubling down on fossil fuels. In particular, he has become one of the most prominent tech executives arguing that the future of AI depends on nuclear power, both existing reactors and new designs that can run around the clock.

In recent comments, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has said that energy, not chips, will be the ultimate bottleneck for AI, and that the industry will need huge amounts of electricity from stable sources to keep scaling. He has tied that argument directly to the case for more reactors, describing why Nvidia’s Jensen Huang Thinks AI’s Future Depends on Nuclear Power. By putting nuclear at the center of his roadmap, he is effectively telling governments that if they want to host the next wave of AI investment, they will need to back firm, low carbon generation at scale.

Data centers, nuclear fleets and the Three Mile Island signal

Huang’s nuclear advocacy is not happening in a vacuum. Power companies that own large reactor fleets are already exploring how to pair those assets with AI data centers, betting that long term contracts with hyperscalers and chipmakers can finance upgrades and new units. One of the most striking examples involves the largest nuclear plant owner in the United States, which has looked at reopening Three Mile Island and co locating data centers next to its reactors to supply AI clusters with steady, carbon free power.

That kind of plan illustrates how deeply AI is now intertwined with the future of nuclear policy. When the largest nuclear plant owner talks about reopening Three Mile Island and building data centers on site, it is responding directly to the kind of demand signal Huang is sending about the need for firm power. He has discussed these developments in the context of what is behind AI’s energy demand, highlighting how utilities and grid operators are preparing for a world where data center loads can be so large that, if not managed carefully, users drop off the grid, a concern he has addressed in detail when explaining AI’s energy demand.

Inside Huang’s explanation of AI’s energy appetite

Huang has tried to demystify why AI workloads look so power hungry on paper. Training large models requires enormous bursts of computation, and inference at scale can keep clusters running near full tilt for long stretches. He has explained that this is not a sign of waste, but a reflection of how much latent demand there is for smarter software, from recommendation engines to copilots embedded in everyday tools like Microsoft 365 and Adobe Creative Cloud.

In conversations with energy executives, Huang has said that once companies experience what AI can do, they rarely dial back their usage, which is why he warns that planners should not assume users drop off the grid after an initial spike. Instead, he argues that demand tends to plateau at a higher level, which is why he urges utilities to think in terms of multi decade capacity additions rather than short term fixes. He has described how he answered questions about this pattern after having met with grid operators and large customers, emphasizing that the real risk is underbuilding infrastructure, a point he has made explicit when he answered concerns about users dropping off.

Bold predictions about AI’s trajectory and energy use

Huang’s confidence in AI’s growth is matched by the scale of his predictions. He has argued that generative AI is not a niche feature but a new computing platform that will touch every industry, from automotive to healthcare to finance. In his view, the shift is as profound as the move from mainframes to PCs or from desktops to smartphones, and it will drive a corresponding transformation in how much and what kind of electricity the digital economy consumes.

Those views surfaced in a series of remarks that were framed as 6 Bold Statements By Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang On AI’s Future, where he described how generative AI will reshape software and hardware design. One of his key points was that accelerated computing reduces energy consumed for a given workload, which he contrasted with the trajectory of traditional CPU scaling. By Dylan Martin’s account of those comments, Huang was explicit that the industry must embrace architectures that deliver more performance per watt, a theme he has returned to repeatedly when outlining his bold statements on AI’s future.

The policy and investment stakes of Nvidia’s message

Huang’s attempt to calm the AI power panic is not just a PR exercise, it is a bid to shape how regulators and investors respond to the next wave of data center construction. If policymakers accept his framing, they are more likely to prioritize grid upgrades, nuclear restarts and new transmission lines over blunt restrictions on AI facilities. That would align with Nvidia’s commercial interests, but it would also lock in a long term bet that efficiency gains and clean power can keep pace with demand.

For utilities and infrastructure funds, Huang’s stance offers both reassurance and a challenge. On one hand, his emphasis on accelerated computing and nuclear backed data centers suggests a path where AI growth is compatible with climate targets. On the other, his warnings about sustained demand mean that underinvestment could leave regions scrambling for capacity, with higher prices and reliability risks. As Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang continues to argue that AI will help, not hinder, the energy transition, the real test will be whether governments and grid operators move quickly enough to build the low carbon systems his vision assumes.

More from MorningOverview