The first X-ray portrait of comet 3I/ATLAS has turned a rare interstellar visitor into a powerful new probe of the space between the stars. By catching the comet in high-energy light, ESA’s XMM-Newton observatory has revealed how its gas interacts with the solar wind and opened a fresh window on the chemistry of material that formed around another star.

Instead of a simple pretty picture, the X-ray view exposes a dynamic collision zone where charged particles from the Sun slam into neutral atoms streaming off the comet. I see this as a turning point in how astronomers study interstellar objects, shifting the focus from their orbits and shapes to the invisible physics and gases that surround them.

Why 3I/ATLAS is not just another comet

Comet 3I/ATLAS is only the third known interstellar object to sweep through our solar system, and that alone makes it a scientific prize. It was first spotted by the ATLAS survey telescopes, which scan the sky for moving objects, and follow-up work quickly showed that its path could not be explained by a long, stretched orbit around the Sun, marking it as a true outsider passing through our neighborhood once before vanishing back into deep space. As one observatory put it, this is an “otherworldly guest” that is simply passing through our solar system, not bound to return.

That status has fueled both serious research and wilder speculation. As 3I/ATLAS reappeared from behind the Sun, some coverage leaned into the idea that it might be artificial, but astronomers have stressed that its behavior matches a natural comet, with a nucleus shedding gas and dust as it warms. Reporting on its reemergence noted that There has been some frenzied speculation about alien spacecraft, but the data so far point to a frozen body shaped by the same basic processes that govern comets born in our own planetary system.

From optical images to high-energy light

Before XMM-Newton ever turned toward 3I/ATLAS, astronomers were already building a detailed picture of the comet in visible light. The Hubble team released a new image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope of the interstellar comet, showing a compact nucleus wrapped in a developing coma and tail as it moved inward. That view, captured by The Hubble group, underscored how quickly the object was waking up as sunlight began to heat its ices.

Ground-based and space-based optical images also showed 3I/ATLAS brightening as it approached the inner solar system, behaving much like homegrown comets that flare when their ice sublimates. Observers noted that as Comets typically brighten while closing in on the Sun, the same pattern was emerging here, with jets and a thicker coma hinting at more vigorous activity. One report described how Comets typically brighten as they near the Sun, and 3I/ATLAS appears to be following that script, suggesting that its surface is rich in volatile material ready to vaporize.

XMM-Newton’s first X-ray portrait

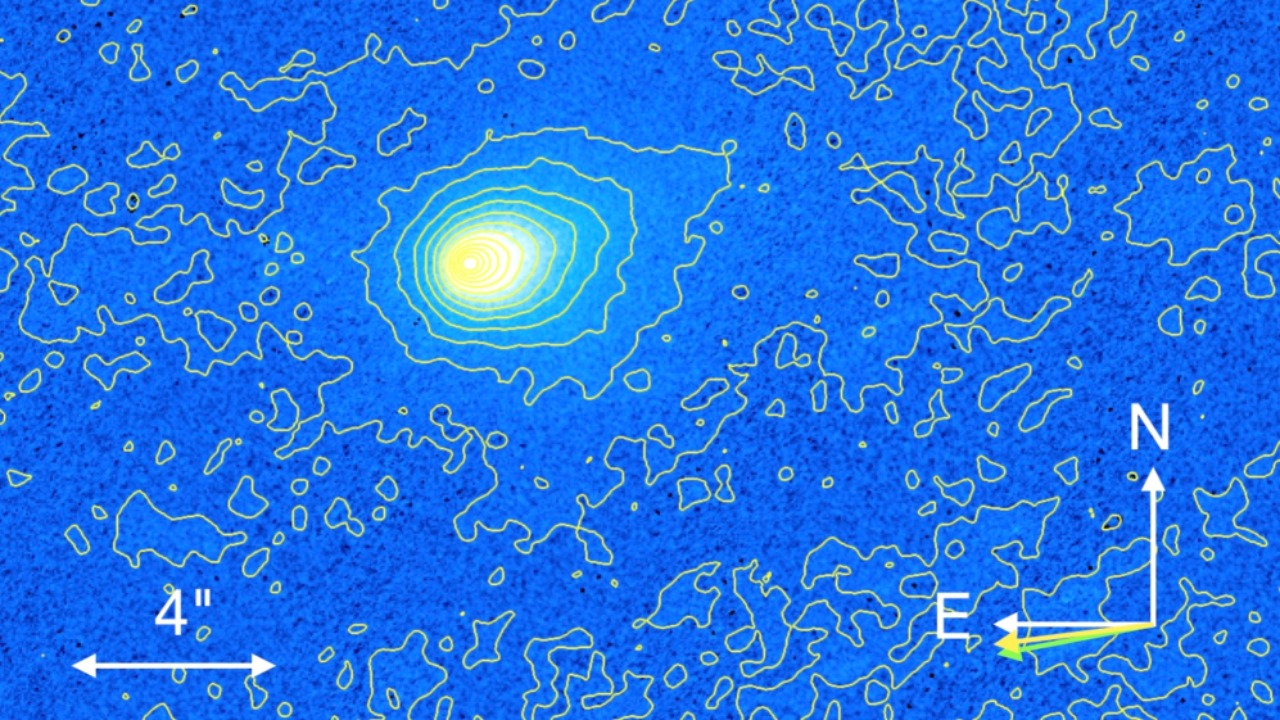

The leap from optical to X-ray imaging came when ESA’s XMM-Newton observatory trained its instruments on the comet and captured the first high-energy view of an interstellar comet. The mission, formally known as the X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission, used its sensitive detectors to record a faint but distinct glow around 3I/ATLAS, turning a point of light into a structured X-ray source. ESA highlighted this milestone by releasing an image that shows the comet as a soft, extended patch, a view shared through an XMM-Newton visual that anchors the new result.

To get that image, XMM-Newton watched 3I/ATLAS for an extended stretch, building up enough photons to separate the comet’s signal from background noise. The observatory’s team explained that XMM-Newton watched 3I/ATLAS for 20 hours and saw it glowing as gases from the comet collided with the solar wind, a process that lights up the surrounding space in X-rays. That long stare, described in a mission update that noted how XMM-Newton watched 3I/ATLAS for roughly 20 hours, is what turned a fleeting visitor into a detailed X-ray target.

Inside the EPIC view: how the data were taken

At the heart of this observation is XMM-Newton’s European Photon Imaging Camera, or EPIC, which is designed to capture faint X-ray sources with high sensitivity. For 3I/ATLAS, the team relied on the EPIC-pn camera, the most sensitive X-ray camera on the spacecraft, to collect enough photons to map the comet’s emission. A detailed account of the campaign notes that European Photon Imaging Camera EPIC-pn was central to the effort, turning the observatory into a kind of high-energy camera obscura for this interstellar object.

The observing run itself stretched over nearly two days of clock time, with the spacecraft repeatedly scanning the comet’s position as it moved against the background sky. According to one technical breakdown, the data were collected from 23:20 on November 26 to 20:38 on November 28, 2025, with an effective exposure of 17 hours, a figure that reflects the usable time once intervals of high background and detector noise were removed. That precise timing, including the reference to 38 in the end time, underscores how carefully the team had to plan to catch a fast-moving, faint target in X-rays.

What X-rays reveal about cometary chemistry

The real power of X-ray observations lies in what they say about the gases streaming off 3I/ATLAS and how those gases respond to the solar wind. When neutral atoms and molecules from the comet’s coma collide with highly charged ions from the Sun, they undergo charge exchange, a process that leaves the ions in excited states that then emit X-rays at characteristic energies. ESA’s analysis of the new data emphasizes that this makes X-ray observations a powerful tool because they allow scientists to detect and study gases that other instruments struggle to see, including key molecules like carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen (N₂). In its description of the spectrum, the agency notes that They allow scientists to probe CO and nitrogen (N₂) in ways that complement optical and infrared work.

For an interstellar comet, that chemical insight is especially valuable. The mix of gases in 3I/ATLAS carries clues about the temperature and composition of the disk where it formed, long before it was ejected into interstellar space. By comparing the X-ray spectrum of this comet with those of solar system comets, researchers can test whether its ices are richer or poorer in certain species, or whether the charge exchange process unfolds differently in material that has spent eons between the stars. The initial XMM-Newton results, presented in the context of XMM-Newton sees comet 3I/ATLAS in X-ray light, point to a spectrum shaped by familiar physics but potentially distinctive in its detailed line strengths.

How 3I/ATLAS fits into the history of cometary X-rays

To understand why this observation matters, it helps to place it in the broader story of cometary X-ray emission. In our solar system, comets are known to emit X-rays, a discovery that initially surprised astronomers who thought of these objects as cold, dark bodies. The first detection came in the 1990s from Comet Hyakutake, and follow-up work showed that the interaction between cometary gas and the solar wind creates a natural high-energy laboratory. A mission overview on 3I/ATLAS notes that In our solar system, comets have become a standard target for X-ray observation because of this effect.

What makes 3I/ATLAS different is that it brings material from another stellar system into that same framework. By treating it as a “cometary interloper,” as one mission summary puts it, researchers can ask whether the same charge exchange processes produce similar spectra in gas that condensed around a different star. The XRISM team, which has also observed 3I/ATLAS, framed the comet as a target for X-ray observation precisely because it extends the established science of cometary X-rays into interstellar territory, offering a rare test of how universal those physical processes really are.

A multi-mission campaign around a rare visitor

The XMM-Newton image is not happening in isolation, and that is part of what makes the 3I/ATLAS campaign so rich. Optical and ultraviolet views from Hubble, ground-based telescopes, and survey instruments are being combined with X-ray data to build a multiwavelength portrait of the comet’s activity. The Hubble team’s release of a new image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope of the interstellar comet, highlighted in coverage of Hubble Space Telescope of the object, shows the fine structure of the coma and tail that the X-ray instruments cannot resolve, but which help interpret where the gas is densest and how it is flowing.

Other X-ray missions are joining in as well. XRISM has observed the comet as a “cometary interloper,” while ESA’s own social media channels have shared early looks at the XMM-Newton data. One post from the agency’s science account noted that Our @ESA_XMM has observed comet #3IATLAS in X-ray light, explaining that when gas molecules streaming from a comet collide with the solar wind, they emit X-rays that can be mapped by the observatory. That kind of coordinated messaging reflects a broader strategy: treat 3I/ATLAS as a once-in-a-generation laboratory and throw as many instruments at it as possible while it is still bright enough to study.

Public fascination and the “alien spacecraft” narrative

Interstellar visitors naturally invite big-picture questions, and 3I/ATLAS has been no exception. As it emerged from behind the Sun and became visible again, some commentators leaned into the idea that it might be an engineered object, echoing debates that surrounded the earlier interstellar object ‘Oumuamua. Coverage of its reappearance noted explicitly that There has been some frenzied speculation in the media that 3I/ATLAS might be an alien spacecraft, but most astronomers see no need for such an explanation given how closely its behavior tracks that of natural comets.

From my perspective, the X-ray data are a powerful antidote to that kind of hype. The emission pattern that XMM-Newton sees is exactly what one expects when neutral gas from a comet interacts with the solar wind, and the spectrum is shaped by familiar atomic transitions rather than anything exotic. Even popular science coverage that plays up the drama of interstellar visitors tends to ground its narrative in the physics, as seen in a feature that juxtaposed Comet SWAN’s fleeting appearance with a discussion of how Esa’s Xmm Newton Takes First Ever Ray Photo Of Interstellar Comet 3IATLAS and asked What Did ESA’s XMM-Newton actually find. The answer, so far, is a natural object behaving in line with well-tested theories, which is its own kind of remarkable.

What this means for future interstellar visitors

The success of XMM-Newton’s observation is already shaping how astronomers think about the next interstellar object that wanders through. If 3I/ATLAS can be turned into an X-ray source bright enough to study in detail, then future visitors might be targeted even earlier, with coordinated campaigns that bring together optical, infrared, radio, and high-energy observatories. The Lowell Observatory’s description of 3I/ATLAS as an “otherworldly guest” discovered by the ATLAS survey telescopes underscores how crucial wide-field searches are, and the reference to the survey approach hints at how next-generation facilities like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory could give missions like XMM-Newton more lead time.

At the same time, the 3I/ATLAS campaign is a reminder that X-ray astronomy is not just about black holes and neutron stars. Comets, especially those from beyond our system, are emerging as key targets for understanding how the solar wind shapes the space environment and how planetary systems exchange material with the wider galaxy. ESA’s own outreach around the result, including the detailed explanation of how Dec observations of CO and nitrogen (N₂) can trace cometary gases, points toward a future in which every interstellar visitor is treated as a full-spectrum laboratory. If 3I/ATLAS is any guide, the next one will not just be photographed, it will be dissected across the electromagnetic spectrum.

More from MorningOverview