SpaceX says one of its Starlink internet satellites came perilously close to being struck by a spacecraft from a Chinese launch, a near miss that highlights how crowded and politically fraught low Earth orbit has become. The company’s account of the incident is not just a technical footnote, it is the latest flashpoint in a growing contest over who bears responsibility for keeping orbital highways safe.

As commercial constellations expand and national space programs accelerate, the margin for error is shrinking faster than the rules are evolving. A single collision could scatter debris across key orbits, threatening everything from broadband networks to crewed stations, and the dispute between SpaceX and Chinese operators shows how quickly safety concerns can harden into geopolitical friction.

What SpaceX says happened in orbit

According to SpaceX, the close call unfolded when a spacecraft deployed from a Chinese rocket passed dangerously near a Starlink satellite, raising the probability of a collision far beyond what operators consider routine. The company has framed the episode as a textbook example of how a lack of timely data sharing and coordination can turn a predictable conjunction into a serious hazard, especially in the dense shell of low Earth orbit where Starlink operates. Reporting on the event describes a Chinese payload released into an orbit that intersected the path of a Starlink craft, with the encounter characterized as a near slam rather than a benign flyby, underscoring the severity of the approach as SpaceX tells it, as detailed in coverage of the spacecraft from Chinese launch.

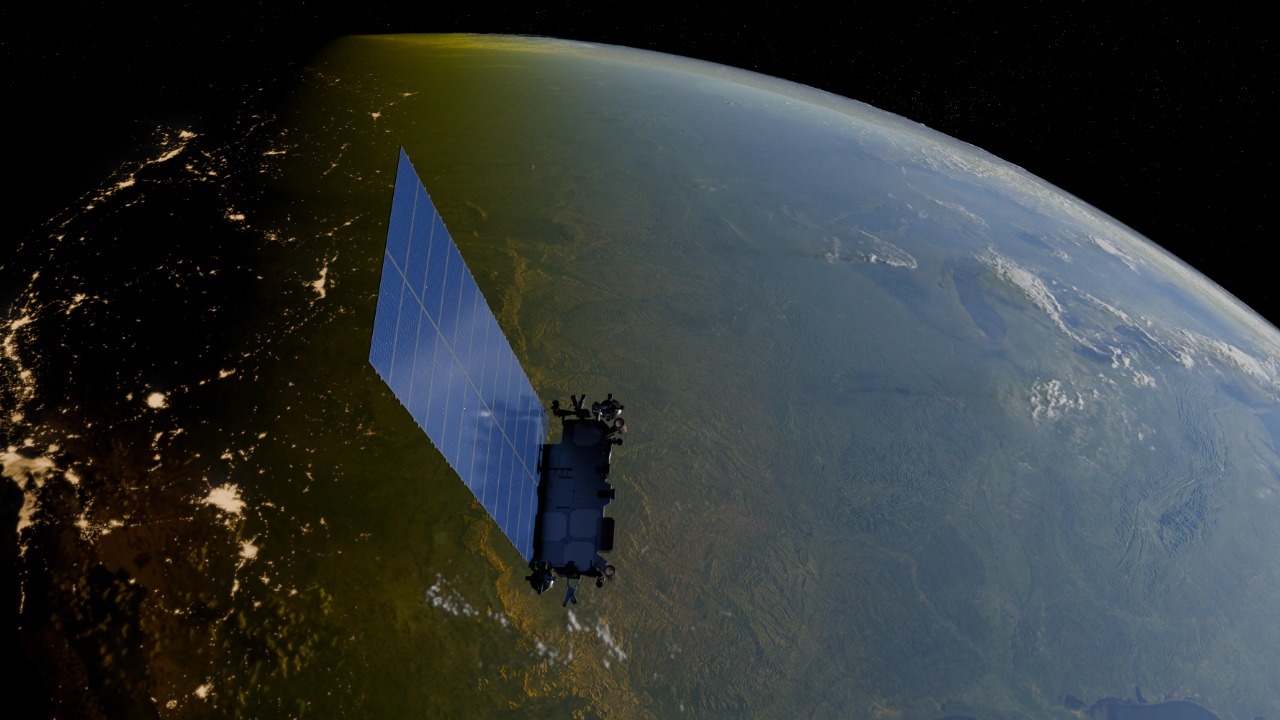

SpaceX’s account emphasizes that the Starlink satellite involved was part of its operational broadband network, not a test platform or decommissioned unit, which meant any impact could have had immediate consequences for customers and for the broader constellation. The company has previously highlighted how its automated collision avoidance system can maneuver satellites when it has reliable tracking data, but in this case it argues that incomplete information about the Chinese spacecraft’s trajectory limited its options. A more technical description of the geometry of the pass, including the altitude and orbital parameters of the Starlink vehicle, appears in a focused discussion of the Starlink satellite (56120) at 560 km altitude, which SpaceX has cited as evidence that the encounter was uncomfortably close.

The Chinese launch and its mysterious payload

On the other side of the story is the Chinese mission that put the problematic spacecraft into orbit, a launch that Chinese firm CAS Space has publicly celebrated as a success. CAS Space reported that it had successfully lofted nine satellites using its Kinetica-1, also known as Lijian-1, rocket on a Wednesday flight, describing the mission as a milestone for its commercial ambitions. Among those nine payloads was a spacecraft designated 67001, which SpaceX has identified as the object that later came close to one of its Starlink satellites, a detail that appears in reporting on how CAS Space reported successfully launching nine satellites on Wednesday using its Kinetica-1/Lijian-1 rocket and that one of the payloads is 67001.

From the Chinese perspective, the mission was a straightforward deployment of commercial and experimental satellites, part of a broader push to build out domestic launch capabilities and orbital infrastructure. There has been no detailed public breakdown from Chinese authorities of the operational profile of spacecraft 67001, leaving outside analysts to rely on tracking data and foreign operator accounts to reconstruct its behavior. That information gap is precisely what SpaceX points to when it argues that the risk was avoidable, saying that if operators had better insight into the Chinese payload’s maneuvers, the Starlink satellite could have been steered clear with more confidence, a theme echoed in later commentary about how a Chinese Deployed Satellite Risked Colliding With Starlink.

Why this near miss matters for a 9,300‑satellite network

The stakes of any close approach involving Starlink are amplified by the sheer scale of the constellation. SpaceX now operates nearly 9,300 Starlink satellites in orbit, more than 3,000 of which have launched this year alone, a growth curve that has turned the company into the dominant player in low Earth orbit broadband. Those figures, cited in coverage of the Starlink company currently operating nearly 9,300 satellites, more than 3,000 launched this year, illustrate how any single incident is no longer an isolated anomaly but part of a statistical reality where thousands of spacecraft share overlapping orbital shells.

For SpaceX, a collision would not just mean the loss of one satellite, it could generate debris that threatens neighboring Starlink units and other operators’ spacecraft, potentially triggering a cascading effect across the network. The company has argued that its automated avoidance system and deorbiting practices are designed to mitigate that risk, but the more crowded the environment becomes, the more those systems depend on accurate, shared data. The near miss with the Chinese spacecraft is therefore being framed internally as a warning shot, a sign that even a well resourced operator can be blindsided when another party’s satellite appears without sufficient coordination in the same orbital lane.

A reversal of roles after earlier Chinese complaints

The current dispute also flips the script on a diplomatic spat that played out several years ago, when Chinese officials accused SpaceX of putting their astronauts at risk. At that time, China told the United Nations that its Tiangong space station had been forced to take what it called “preventive collision avoidance control” during two close encounters with Starlink satellites, arguing that the burden of maneuvering had fallen unfairly on its crewed outpost. The episode triggered a wave of criticism on Chinese social media, where users blasted Elon Musk and questioned why a private company’s satellites were allowed to come so close to a national space station, a backlash captured in reporting that described how China’s Tiangong space station was reportedly forced to take ‘preventive collision avoidance control’ during two ‘close encounters’ with SpaceX’s Starlink satellites.

Back then, Beijing framed Starlink as the aggressor and Tiangong as the victim of an increasingly congested orbital environment, using the incident to call for stronger international rules on mega constellations. Now, with SpaceX alleging that a Chinese deployed spacecraft nearly struck one of its own satellites, the roles are reversed, and each side can point to a near miss where it claims to have been on the receiving end of risky behavior. The symmetry underscores how fragile the politics of space safety have become, with both China and SpaceX able to cite specific episodes where they say the other party’s hardware came too close for comfort.

How SpaceX frames the core problem: coordination, not physics

In public comments about the incident, SpaceX executives have been careful to say that the main threat is not the laws of orbital mechanics but the lack of human coordination that sits on top of them. One executive put it bluntly, saying, “Most of the risk of operating in space comes from the lack of coordination between satellite operators, this needs to change,” a line that captures the company’s argument that better data sharing and communication could dramatically reduce the odds of dangerous conjunctions. That sentiment appears in coverage that quotes the phrase Most of the risk of operating in space comes from the lack of coordination between satellite operators, tying the company’s policy stance directly to the near miss.

By focusing on coordination, SpaceX is implicitly arguing against more restrictive caps on constellation size or unilateral blame for any one operator. Instead, it is pushing for a regime where satellite owners share precise ephemeris data, respond quickly to conjunction alerts, and agree on common thresholds for when to maneuver. The company has said it is willing to provide help “however we can” to improve that ecosystem, but the clash with Chinese operators shows how difficult that will be in practice when national security sensitivities and commercial competition limit what data can be shared. The near collision with spacecraft 67001 therefore becomes a case study in how technical solutions can only go so far without political and institutional buy in.

What the near miss looked like from the ground

Outside the corporate and diplomatic channels, the incident also filtered into the public sphere through space tracking enthusiasts and online communities that monitor orbital traffic. Amateur analysts and fans of commercial spaceflight seized on the story of a Starlink internet satellite coming close to a Chinese spacecraft, using it to illustrate how crowded the skies have become and how quickly a routine launch can turn into a potential hazard. One widely shared discussion described how A SpaceX Starlink internet satellite recently came very close to a possible collision in orbit, capturing the alarm many observers felt at the idea of two uncrewed machines nearly smashing into each other at orbital speeds.

These ground level conversations often blend technical curiosity with a sense of unease about the long term sustainability of spaceflight. Commenters worry that each new near miss is a roll of the dice that could eventually come up bad, especially as more nations and companies launch satellites without a unified traffic management system. The viral spread of the Starlink story in these forums shows how orbital safety has moved from a niche concern of engineers and diplomats into a mainstream topic that shapes public perceptions of both commercial operators and national space programs.

The broader risk of satellite collisions

Experts have long warned that as the number of satellites multiplies, the risk of accidental collisions will rise unless operators change how they share information. One widely cited explanation puts it succinctly, noting that “When satellite operators do not share ephemeris for their satellites, dangerously close approaches can occur in space,” a statement that directly links data transparency to collision risk. That warning appears in a discussion of When satellite operators do not share ephemeris for their satellites, dangerously close approaches can occur in space, which uses the Starlink near miss as a fresh example of a problem that has been building for years.

In practical terms, ephemeris data is the precise information about where a satellite is and where it is going, the raw material that allows collision avoidance systems to predict conjunctions and plan maneuvers. When that data is incomplete, outdated, or withheld for security reasons, operators are forced to make decisions based on rougher tracking from ground based radars and telescopes, which can leave them uncertain about how close another object will actually come. The Starlink incident with the Chinese spacecraft illustrates how that uncertainty can translate into elevated risk, even when both sides may be acting in good faith to avoid a crash.

From technical scare to geopolitical flashpoint

What makes this near miss more than a technical scare is the geopolitical context in which it occurred. SpaceX is a private company, but it operates under U.S. regulation and provides services that have become strategically important, from broadband in remote regions to connectivity in conflict zones. China, for its part, views space as a critical domain for national prestige and security, and has invested heavily in launch vehicles, satellites, and the Tiangong station. When a spacecraft from a Chinese launch nearly hits a Starlink satellite, each side can interpret the event through a lens of strategic competition, even if the underlying cause is a mundane coordination failure.

That dynamic is not new. Earlier, when China complained that Starlink satellites had forced Tiangong to maneuver, it used the incident to argue that foreign mega constellations posed a risk to its crewed missions and to call for stronger international oversight. Now, with SpaceX alleging that a Chinese deployed satellite created a dangerous conjunction, U.S. voices can point to the episode as evidence that Chinese operators also contribute to orbital risk. The result is a feedback loop where each near miss becomes fodder for broader narratives about responsibility and recklessness in space, making it harder to build the trust needed for the very coordination that could prevent future scares.

What needs to change before the next close call

For all the finger pointing, the technical prescription that emerges from the Starlink incident is relatively clear. Operators need to share more accurate and timely orbital data, agree on common thresholds for when to maneuver, and establish reliable channels for direct communication when a conjunction alert appears. That could mean expanding existing voluntary databases, creating new multilateral agreements, or empowering a neutral body to act as a kind of air traffic controller for low Earth orbit. SpaceX’s own messaging, from its emphasis on coordination to its willingness to assist other operators, suggests it would support such moves, provided they do not single out its constellation for punitive limits.

Whether China and other emerging space powers are willing to embrace that level of transparency is a harder question, especially when some satellites carry military or dual use payloads. Yet the alternative is a future where near misses like the one involving spacecraft 67001 and the Starlink satellite become more frequent, each one a roll of the dice that could eventually produce a debris generating collision. The earlier complaints about Starlink’s proximity to Tiangong, the latest scare involving a Chinese launch, and the growing chorus of experts warning about unshared ephemeris all point in the same direction: without better coordination, the odds of a catastrophic accident in orbit will only rise.

More from MorningOverview