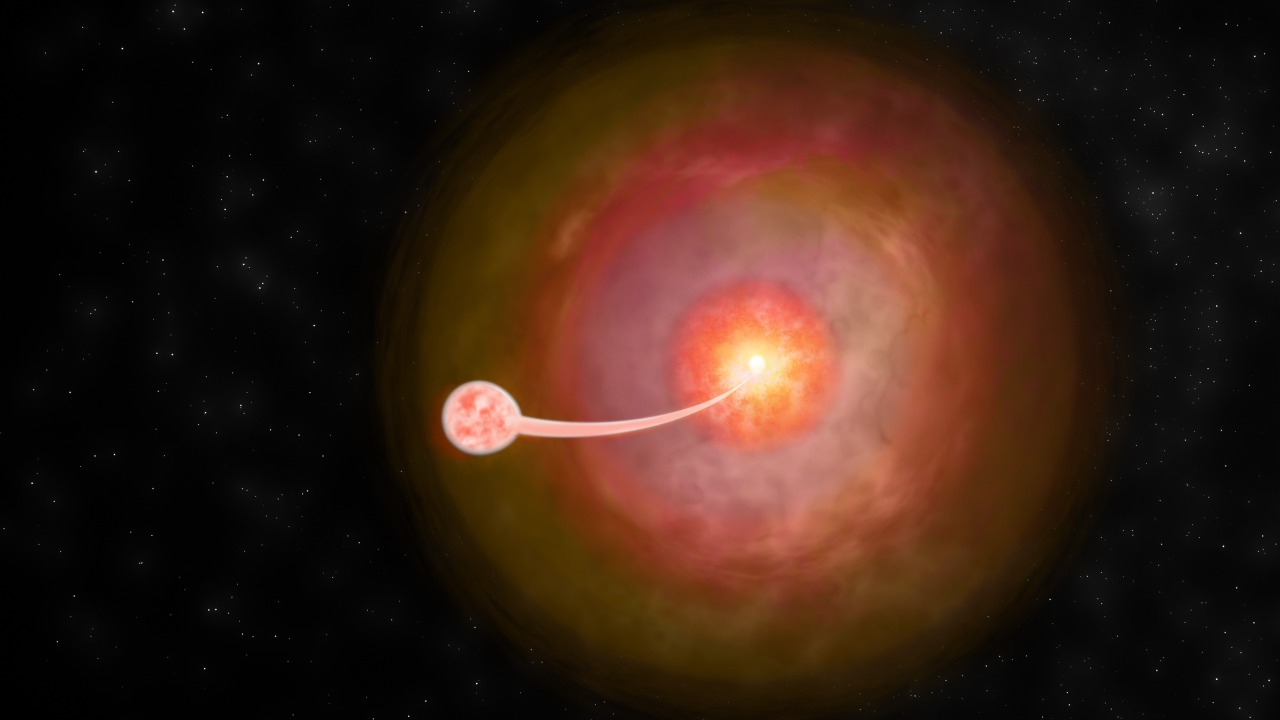

Two stellar explosions that lit up the sky in 2021 have now been dissected in unprecedented detail, revealing tangled shells, colliding flows of gas, and structures that defy decades of textbook diagrams. By resolving these novae almost as if they were in our own backyard, astronomers have turned what once looked like simple flashes into intricate laboratories for extreme physics.

I see these twin blasts as a turning point in how we picture dying stars: no longer as neat, spherical fireballs, but as restless engines that spit out clumps, jets, and shock fronts that evolve minute by minute. The new observations do not just sharpen the images, they force a rewrite of how white dwarfs erupt, how they feed on companion stars, and how they seed their surroundings with fresh material.

Two distinct nova events that changed the playbook

The recent breakthrough centers on two distinct nova events that erupted in 2021, each involving a white dwarf suddenly brightening as it dumped a shell of material into space. One of them, Nova V1674 Herculis, has already become a reference point for how complex these explosions can be, while the second nova in the pair provides a crucial comparison that shows this is not a one-off curiosity but part of a broader pattern. By tracking both blasts from their earliest outbursts, astronomers could watch the geometry of the ejecta unfold instead of inferring it long after the fact.

In the new work, the team explicitly framed their campaign around these Two Distinct Nova Events, Nova V1674 Herculis and a second nova that also erupted in 2021, using high resolution imaging to capture the changing shapes of the outflows. That choice matters, because it allowed them to compare how two different systems, each with its own orbital dance and accretion history, produced surprisingly similar signatures of layered shells and asymmetric jets. Instead of treating each nova as an isolated oddity, the observations tie them together as part of a new, more chaotic class of stellar eruptions.

Close-up images that finally resolve the blast

For decades, most nova studies relied on light curves and spectra, which are powerful but indirect tools that leave plenty of room for interpretation. What changes now is that astronomers have finally captured close-up images of these explosions as they unfold, resolving structures that used to be blurred into a single fuzzy blob. I see that as the astrophysical equivalent of switching from an old analog TV to a 4K screen, where details that were once invisible suddenly dominate the story.

The new observations let researchers See exploding stars like never before, with close-up images of novae that reveal multiple outflows, changing shapes, and complex, time changing explosions in unprecedented detail. Instead of a single expanding ring, the images show nested shells, knots, and arcs that twist and brighten as shock waves plow through the surrounding gas. That level of spatial detail, combined with rapid time sampling, turns each nova into a movie rather than a snapshot, and it is in those movies that the unexpected structures leap out.

Nova V1674 Herculis and the shock of colliding outflows

Among the two events, Nova V1674 Herculis stands out as the clearest sign that the old, simple picture of nova eruptions is no longer tenable. Rather than a single, smooth shell of gas expanding away from the white dwarf, the data show at least two distinct outflows that crash into each other, creating shock fronts and bright knots where the flows collide. That kind of internal traffic jam inside the ejecta is exactly the sort of structure that standard one shot models struggle to explain.

Researchers studying Nova V1674 Herculis reported that the blast involved two colliding outflows of gas, a configuration that upends the longstanding theory that novae simply eject a single envelope in one go. In this nova, the first outflow appears to have been overtaken by a faster, later wind, so the collision between them sculpts the observed arcs and filaments. That internal clash does not just rearrange the gas, it also converts kinetic energy into radiation, which helps explain why some parts of the nebula glow far more intensely than others.

Why the old one-shell model no longer works

For much of the modern era of astrophysics, novae were modeled as relatively straightforward thermonuclear runaways on the surface of white dwarfs, ejecting a single, roughly spherical shell of material. That picture was always a simplification, but it held up reasonably well when the only data available were smooth light curves and low resolution images. With the new close-up views, however, the one shell model looks more like a cartoon than a realistic description of what is actually happening.

The detailed images show that, instead of a single envelope, white dwarfs Instead, they eject their accreted envelopes in complex nova explosions that involve multiple outflows and changing geometries. That complexity forces theorists to revisit assumptions about how quickly nuclear burning turns on and off, how the white dwarf’s magnetic field channels the flow, and how the binary orbit shapes the blast. The colliding outflows in Nova V1674 Herculis, combined with the layered structures in the second nova, suggest that eruptions can proceed in stages, with each stage leaving its own imprint on the surrounding space.

What the new structures reveal about white dwarfs

These intricate shells and jets are not just pretty pictures, they are direct clues to the inner workings of white dwarfs that are otherwise too small and distant to resolve. When I look at the patterns in the ejecta, I see fingerprints of the star’s rotation, magnetic field, and accretion history, all encoded in the way the gas is flung into space. The fact that the structures are so asymmetric hints that the underlying engine is anything but uniform.

In the case of Nova V1674 Herculis, the presence of colliding outflows suggests that the white dwarf did not simply ignite once and then shut off, but instead went through at least two distinct phases of mass loss that interacted with each other. The broader campaign on the Two Distinct Nova Events shows that both systems produced complex, multi component outflows, which implies that such behavior may be common rather than exceptional. By tying these structures back to models of how white dwarfs accrete from their companions and how their magnetic fields thread the inflowing gas, astronomers can start to map specific features in the nebula to specific processes on the star’s surface.

From simple flashes to dynamic, evolving explosions

One of the most striking shifts in perspective is temporal rather than spatial. Instead of treating a nova as a single moment of detonation, the new observations reveal it as a dynamic sequence of events that unfolds over days, weeks, and months. Each new outflow, each collision, and each shock front adds another layer to the evolving structure, so the nebula we see at any given time is just a snapshot in a much longer story.

The close-up imaging campaign captured these novae as changing explosions in unprecedented detail, showing how multiple outflows and shells appear, interact, and fade over time. That time resolved view is crucial, because it lets researchers connect specific changes in brightness or spectrum to visible rearrangements in the gas. Instead of guessing which physical process might be responsible for a bump in the light curve, they can now point to a particular shock front or newly launched jet and say, in effect, that is the culprit.

How the findings reshape nova theory and stellar evolution

When theory and observation collide, it is usually theory that has to move, and novae are no exception. The discovery of colliding outflows, nested shells, and asymmetric jets forces modelers to build more sophisticated simulations that can reproduce the observed structures. That is not just an academic exercise, because novae play a key role in how binary systems evolve and how white dwarfs grow toward, or away from, the threshold for more catastrophic explosions.

Analyses of these events, including Nova V1674 Herculis, have already been folded into a broader rethinking of nova physics that has been highlighted in discussions of how dying stars behave when they erupt. In that context, researchers have emphasized that When dying stars cause nova explosions, the resulting structures can be far more complex than the classic spherical shells that once dominated the literature. That complexity feeds back into questions about how much mass the white dwarf actually loses versus how much it retains, which in turn affects whether it might someday cross the line into a Type Ia supernova. In other words, getting the details of these novae right is essential for understanding the life cycles of some of the most important stellar remnants in the universe.

Why these nova images matter far beyond one pair of stars

It would be easy to treat Nova V1674 Herculis and its 2021 companion as exotic curiosities, but that would miss the larger stakes. The same physical processes that sculpt their ejecta, from colliding outflows to magnetically guided jets, are at work in many other astrophysical settings, including young stellar objects, X ray binaries, and even the environments around supermassive black holes. By resolving these novae so clearly, astronomers gain a relatively nearby, well controlled testbed for physics that also shapes galaxies and clusters.

I see the new images as a bridge between small scale stellar explosions and the grander fireworks of the cosmos. The colliding flows in Nova V1674 Herculis echo the shocks seen in supernova remnants, while the layered shells in the second nova resemble the nested bubbles carved by massive stars before they die. As more novae are observed with the same level of detail, patterns will emerge that either confirm or challenge the idea that these two 2021 events are representative. Either way, the message is already clear: when we look closely enough, even familiar stellar outbursts reveal structures we have never seen before, and those structures carry the keys to understanding how stars live, die, and reshape the space around them.

More from MorningOverview