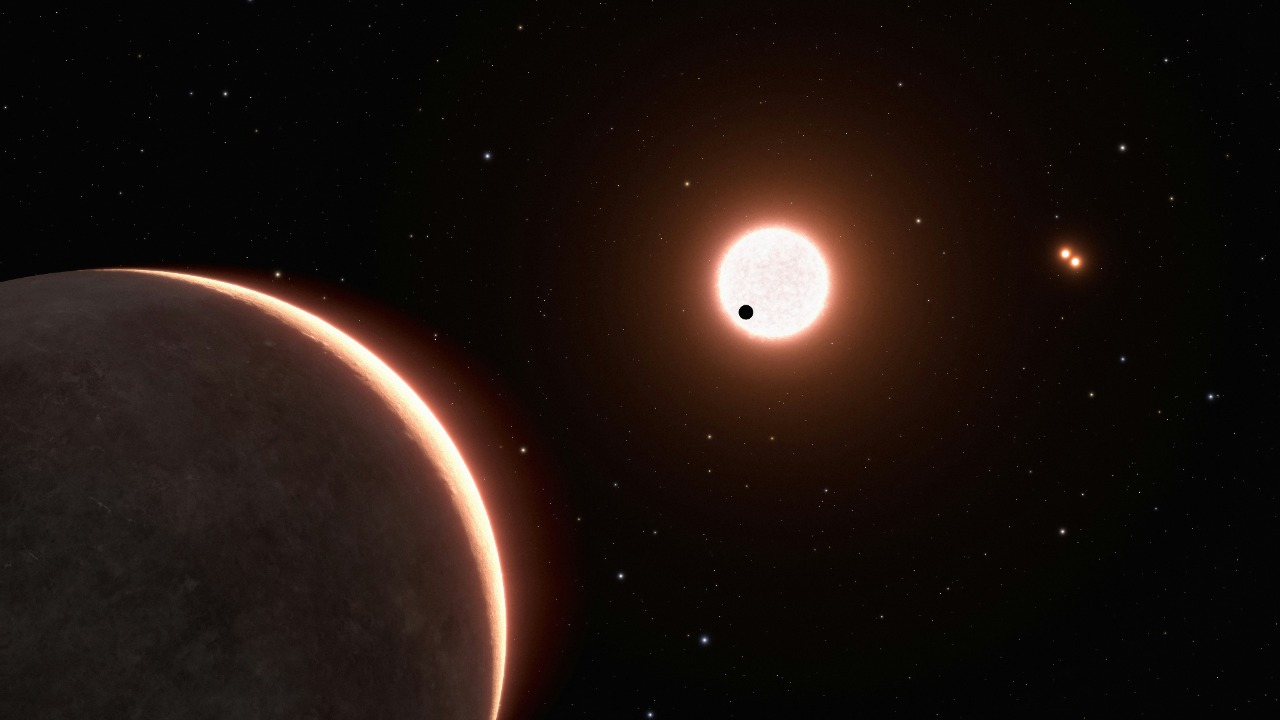

One of the most promising Earth-sized exoplanets may be far more barren than its early billing suggested, with new analyses pointing to a rocky world stripped of the protective gases that make a planet truly habitable. If that verdict holds, it will sharpen a growing realization in astronomy that size and distance from a star are not enough, and that atmospheres are the fragile hinge on which alien habitability turns.

As I follow the latest work on nearby rocky worlds, I see a pattern emerging: planets that look like Earth in mass and orbit can still fail the atmospheric test, either because their gases are blasted away or never accumulate in the first place. That shift in focus, from “Earth-like” surfaces to the invisible envelopes of air around them, is quietly rewriting how scientists rank the most enticing targets in the search for life.

Why an “Earth twin” without air changes the stakes

When astronomers first flag a planet as Earth-like, they usually mean it is roughly the same size and receives a similar amount of starlight, not that it has oceans, clouds, or breathable air. A rocky world that loses its atmosphere, or never builds one, can sit squarely in the so-called habitable zone and still be as lifeless as the Moon. That is why the prospect that a top candidate may actually be airless is so jarring: it exposes how much of our optimism has rested on assumptions about conditions we cannot yet see directly.

Atmospheres are not cosmetic details, they are the machinery that sets surface temperature, shields against radiation, and cycles key chemicals between rock, water, and sky. It is essential to understand how the atmosphere affects the way planets are habitable, since pressure, composition, and retention are among the prime qualifications for having an atmosphere at all, and for keeping liquid water stable on the surface over long stretches of time, as highlighted in work on how atmospheres enable habitability. If a leading Earth-sized exoplanet turns out to be bare rock, it will not just demote one world on a list, it will force a recalibration of what “Earth-like” should mean in the first place.

How close-in planets lose the air they start with

The likeliest culprit behind an atmosphere-free Earth-sized planet is simple proximity. Worlds that orbit very close to their stars are bombarded by intense high-energy radiation and stellar winds that can strip away gases faster than they can be replenished. Over millions of years, that process can erode even a thick primordial envelope, leaving behind a dense, scorched surface that still looks Earth-sized in a telescope but behaves more like a scaled-up Mercury.

Recent modeling of compact planetary systems shows that this erosion is not a rare fluke but a predictable outcome for many close-in worlds, especially those around active stars. With the scheduled observations from JWST due soon for several of these systems, astronomers are preparing to test whether the detection, or lack, of a planetary atmosphere around such close-in exoplanets matches those expectations. If the telescope repeatedly finds bare rock where we once hoped for cloudy skies, it will confirm that many “too close for comfort” planets simply cannot hold on to their air.

Why laboratory dust experiments matter for distant skies

To understand whether a rocky planet can keep an atmosphere, I have to look beyond orbital diagrams and into the physics of the materials that make up its crust and clouds. The structure and composition of silicate grains, the tiny mineral particles that dominate rocky surfaces and can seed clouds, influence how heat is absorbed, how gases interact with the surface, and how quickly an atmosphere might be lost or transformed. Without hard data on how these grains behave under alien pressures and temperatures, models of exoplanet atmospheres risk being elegant guesses.

That is why experimental work on silicate dust has become one of the most intriguing and quickly developing research directions in exoplanet science. By recreating exotic conditions in the lab, researchers can probe the physical and chemical processes that shape the atmospheres of rocky worlds, from condensation and cloud formation to gas-solid reactions that lock volatiles into rock, as detailed in studies on the importance of silicate grain experiments. Those measurements feed directly into climate and escape models, helping scientists decide whether a given planet’s surface is likely to trap gases, recycle them, or let them slip away into space.

From habitability to “atmospheric potential for life”

When a once-promising world looks airless, it is tempting to write it off as irrelevant to the search for life, but that reaction misses a deeper shift in how astrobiologists frame the problem. Instead of asking whether a planet is habitable in the Earth-like sense, researchers are increasingly focused on the chemical potential for habitability, a more nuanced measure of whether an atmosphere, if present, can support the energy and nutrient flows that life would need. That lens matters even for marginal or borderline cases, because it clarifies what is missing and why.

In recent work, a team explicitly framed Their results as an effort to understand not habitability itself but the atmospheric potential for life, emphasizing that the key question is whether there are enough nutrients and reactive molecules in a planet’s air to sustain metabolism, as described in research on measuring atmospheres for nutrients. If a leading Earth-sized candidate truly lacks an atmosphere, it will score near zero on that scale, but the framework itself will still guide how scientists prioritize other targets where thin or unusual atmospheres might still carry the right chemistry even if surface conditions are harsh.

What Modern Earth can and cannot teach us

For decades, I have seen astronomers use Earth as the template for what a habitable planet should look like, but that shortcut is starting to fray. Modern Earth cannot serve as a simple basis for evaluating exoplanets and their potential to support life, because our own atmosphere has changed radically over its 4.5 billion years, from a thick, oxygen-free mix to the oxygen-rich air we breathe today. Any snapshot of Earth at a single moment in its history would give a misleading impression of what is possible on other worlds.

That long evolution matters when we interpret a seemingly barren exoplanet. A world that looks airless today might once have had a dense atmosphere, just as early Earth’s skies bore little resemblance to the present, a point underscored in work on what Modern Earth can teach us about the search for life. That perspective pushes researchers to consider not just whether an atmosphere exists now, but how it might have waxed and waned over time, and whether any habitable window could have opened before the gases were lost.

Redefining “Earth-like” for telescope time and target lists

The possibility that a headline exoplanet is a bare rock is already feeding into how I see astronomers allocate precious observing time. Instead of chasing every Earth-sized world in a temperate orbit, teams are starting to weigh factors like stellar activity, planetary density, and system architecture to estimate whether an atmosphere is likely to survive. A planet that looks perfect on a simple size-and-distance chart may now be downgraded if its star is too volatile or its mass too low to hang on to gas.

This triage is especially important for facilities like JWST, which can only scrutinize a limited number of small planets in detail. Studies that model how close-in exoplanets just cannot hold on to their atmospheres are already shaping future searches for potential signs of life, by steering attention toward worlds where atmospheric retention is more plausible and away from those that are probably stripped, as explored in analyses of when exoplanets cannot hold on to air. If one of the field’s poster-child Earth analogues falls into the latter category, it will accelerate that shift from simple “Earth-like” labels to more demanding atmospheric criteria.

The chemistry we will look for instead

Even as some rocky planets drop off the habitability shortlist, the tools being built to study their atmospheres are becoming more sophisticated. Rather than just checking whether a planet has air, researchers are designing observations to probe specific molecules that trace energy sources and nutrient cycles, such as carbon-bearing gases, nitrogen compounds, and oxidants. The goal is to move beyond a binary habitable or not, and toward a richer map of which worlds have atmospheres that are chemically active enough to matter for biology.

In that context, the loss of an atmosphere on a once-promising planet is not a dead end but a data point that sharpens the contrast with worlds that do retain complex gases. By comparing planets that have been stripped to those that still show spectral hints of clouds or volatile-rich air, scientists can test ideas about how silicate surfaces, stellar radiation, and interior outgassing interact, building on laboratory work that examines the physical-chemical processes in silicate grains. That comparative chemistry will help identify which rocky planets, even if not perfect Earth twins, still offer the atmospheric ingredients that life could, in principle, exploit.

Why a barren “favorite” still moves the field forward

If a leading Earth-sized exoplanet is ultimately confirmed to lack an atmosphere, it will be a disappointment for anyone who hoped it might host oceans or weather. Yet from a scientific standpoint, such a result would be clarifying rather than discouraging. It would validate models that predict severe atmospheric loss for close-in rocky worlds, refine the thresholds at which planets can keep their air, and provide a benchmark for testing how well our theories match reality.

Most importantly, it would push the community to be more precise about what we mean by habitability and to ground that definition in measurable properties rather than wishful thinking. By tying together insights on how atmospheres enable habitability, how close-in planets lose their gases, how silicate grains shape climate, how nutrient-rich air supports life, and how Modern Earth’s history complicates our expectations, I see a field that is steadily trading simple slogans for a more demanding, evidence-based picture of which worlds might truly be alive. An airless “Earth-like” planet, far from being a failure, may be the data point that finally forces that reckoning.

More from MorningOverview