MIT engineers have quietly solved one of the biggest bottlenecks in living-tissue robotics, creating synthetic tendons that let soft muscle pull on hard plastic with far more force and control. By rethinking how biological muscle couples to engineered structures, they have turned fragile lab curiosities into compact machines that sprint, lift, and endure in ways earlier biohybrid robots simply could not. The result is a new class of muscle-powered devices that behave less like science projects and more like practical tools.

From fragile lab toys to work-ready biohybrids

For years, biohybrid robots sat in an awkward middle ground, impressive in concept but too weak and unreliable to do real work. Living muscle could contract, but when it tried to pull on stiff plastics or metals, the connection slipped, tore, or wasted most of the force, so the robots shuffled instead of sprinting and strained instead of lifting. The MIT team attacked that interface problem directly, treating the junction between tissue and structure as the true engine of performance rather than an afterthought in the design.

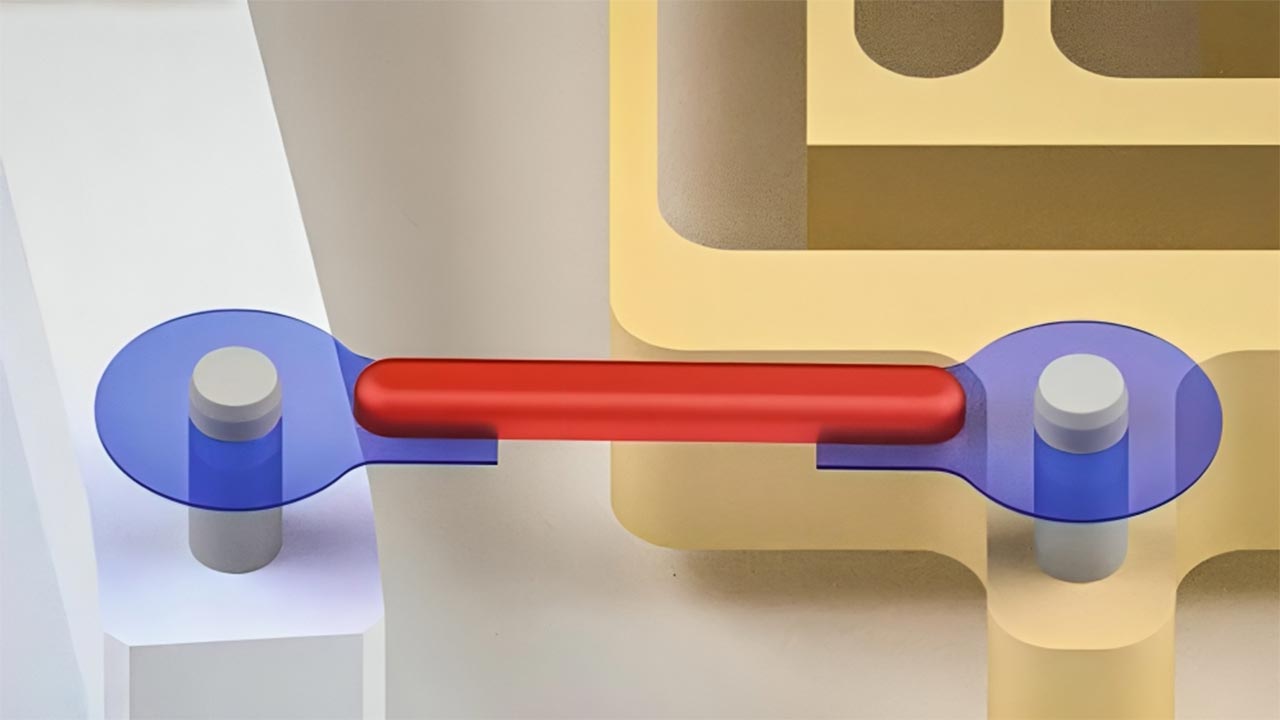

Instead of letting soft muscle fibers glue directly to rigid frames, the researchers recreated a tendon-like layer that spreads loads and keeps the tissue anchored through repeated cycles of motion. In their biohybrid prototypes, this synthetic tendon bridges the gap between living muscle and engineered skeleton, allowing the contractile tissue to transmit far more power without shredding itself. Reporting on the work notes that the MIT team effectively rebuilt the way natural tendons couple muscle to bone, turning a chronic weakness in earlier designs into a useful feature for tiny machines that need both delicacy and strength, a shift highlighted in coverage of how MIT engineers give biohybrid robots a power upgrade.

Why the muscle–plastic connection kept failing

The core problem has always been mechanical mismatch. Biological muscle is soft, wet, and constantly changing as cells grow and remodel, while the plastics and metals used in microrobots are stiff, dry, and unforgiving. When muscle cells contract against a rigid anchor, the stress concentrates at a narrow band of contact, so even a modest pull can rip the tissue free or fatigue it in a few cycles. That is why early muscle-powered swimmers and crawlers tended to degrade quickly, losing motion long before their control electronics or power supplies failed.

Natural systems solve this with tendons that gradually transition from compliant collagen near the muscle to stiffer fibers near the bone, spreading force over a larger area and buffering sudden loads. The MIT group mirrored that logic with synthetic connectors that behave more like living tendon than like a simple glue joint. By inserting this engineered layer between the muscle and the robot body, they turned a brittle interface into a resilient hinge, a change that underpins the dramatic performance gains described in reports on how the MIT team recreated this tendon-like coupling to make the connection a useful feature for tiny machines rather than a chronic liability.

Hydrogel tendons as the missing mechanical layer

The breakthrough came from treating the tendon not as a passive strap but as an active mechanical component with its own carefully tuned properties. The researchers built their artificial tendons from a tough hydrogel, a water-rich polymer network that can stretch, compress, and recover without tearing. Hydrogel materials are soft enough to match the feel of living tissue yet strong enough to carry significant loads, which makes them ideal for bridging muscle and plastic in a single continuous piece. In effect, the tendon becomes a shock absorber and force amplifier in one compact part.

By patterning and shaping this hydrogel, the team created connectors that grab onto muscle on one side and lock into the robot’s frame on the other, so the tissue can contract repeatedly without slipping. Coverage of the work emphasizes that these hydrogel connectors amplify strength, speed, and durability, allowing the robots to work with less muscle tissue while still generating impressive motion. That combination of compliance and toughness is what natural tendons already deliver in animals, and the synthetic version finally gives biohybrid machines a comparable mechanical advantage.

Power-to-weight jumps and the 11× performance leap

Once the tendon problem was solved, the numbers shifted dramatically. With the new connectors in place, the muscle-powered robots no longer wasted most of their contraction in slippage or deformation at the joint, so more of the biological work translated into useful motion. In controlled tests, the team measured how much power the robots could deliver relative to their mass, a key metric for any mobile machine that needs to move quickly or carry a payload. The results showed that the tendon-equipped designs were not just incrementally better but in a different class altogether.

According to the reported data, lead researcher Raman saw that the addition of artificial tendons increased the robot’s power-to-weight ratio by 11 times, a jump that would be transformative in any field of robotics. That 11× boost means a device that once crawled sluggishly can now sprint, or a gripper that barely pinched can now clamp with authority, all without adding bulky motors or heavier batteries. The same reports note that Raman’s measurements captured how the tendon layer let the muscle do more work with each contraction, a finding summarized in coverage that explains how overall, Raman saw that the addition of artificial tendons increased the robot’s power-to-weight ratio by 11 times, underscoring just how much performance had been trapped at the interface.

Threefold speed and 30× force: what the numbers really mean

Raw power-to-weight is only part of the story. For practical applications, speed and force matter just as much, and here the tendon system delivered equally striking gains. When the team compared robots powered by muscle alone to those using the new tendon connectors, they saw that the tendon-equipped machines moved far faster and pushed far harder. In effect, the same biological engine, when properly coupled, behaved like a much larger actuator without any extra cells or energy input.

Reporting on the experiments notes that real-muscle robots gained threefold speed and 30× force with the new tendon system, a combination that turns gentle twitching into decisive motion. That threefold increase in speed means a swimmer or crawler can cover more ground in the same time, while the 30× jump in force opens the door to gripping, lifting, or pushing tasks that were previously out of reach for soft biohybrid devices. The contrast is especially clear in side-by-side comparisons where one robot powered by muscle alone lags behind a nearly identical machine equipped with the tendon layer, a difference highlighted in analysis of how real-muscle robots gain threefold speed and 30× force with the new tendon system.

Inside the Advanced Science study and the role of Nov

The technical details of this work were laid out in a peer-reviewed study that framed artificial tendons as a general strategy for muscle-powered machines. In that paper, which appeared in the journal Advanced Science, the authors described how they fabricated the tendon structures, seeded them with muscle cells, and integrated the resulting units into small robotic platforms. The study did not treat the tendon as a one-off trick but as a modular component that could be tuned for different geometries, stiffness levels, and motion profiles, much like springs or gears in traditional mechanical design.

By publishing in Advanced Science, the team signaled that this is not just a clever lab demo but a platform others can build on. The article explains how the artificial tendons made from tough materials allowed the robots to operate with higher loads and more complex motions, while still relying on living muscle as the actuator. It also situates the work within a broader push toward adaptive, autonomous exploratory machines that can navigate environments where conventional motors struggle. Coverage of the study notes that in a study appearing in the journal Advanced Science, the researchers developed artificial tendons made from tough materials to support exactly this kind of adaptive, muscle-driven robotics.

Dec, Nov, and the pace of tendon innovation

The timeline of this research underscores how quickly the field is moving once the tendon concept clicked into place. Earlier in the year, reports highlighted how MIT engineers had begun to recreate tendon-like structures to solve the chronic problem of connecting soft muscle to stiff plastic, a step that marked a turning point for biohybrid design. Those early demonstrations showed that even relatively simple tendon geometries could stabilize the muscle–plastic interface and unlock more reliable motion, setting the stage for the more aggressive performance gains that followed.

By the time the detailed performance data emerged, the narrative had shifted from proof-of-concept to quantifiable leap. Coverage from Nov described how the artificial tendons made from tough materials were integrated into robots tested for speed, force, and endurance, while later reports from Dec emphasized how the same tendon strategy could be generalized to different robot shapes and tasks. Along the way, key figures like Raman and entities such as Dec and Nov became shorthand markers for distinct phases of the work, from initial tendon recreation to full performance characterization, each phase building on the last to push biohybrid robots closer to real-world utility.

What stronger biohybrid robots can actually do

With threefold speed, 30× force, and an 11× jump in power-to-weight, the obvious question is what these muscle-powered machines might be used for. The most immediate opportunities lie in environments where small size, gentle touch, and high agility matter more than raw torque, such as navigating delicate tissues in medical procedures or exploring tight, cluttered spaces in industrial plants. A tendon-stabilized muscle actuator can squeeze through gaps, conform to irregular surfaces, and apply force in a more distributed way than a rigid motor, which is valuable when the surrounding structures are fragile or unpredictable.

At the same time, the improved durability and efficiency make it easier to imagine swarms of such robots operating for long periods without constant replacement. In microfluidic labs, for example, muscle-powered pumps could drive flows with fine-grained control, while in soft grippers, tendon-coupled muscle bundles could handle items as varied as ripe fruit and electronic components without crushing them. The fact that the robots can now work with less muscle tissue, thanks to the hydrogel connectors that amplify strength and speed, also reduces the biological overhead, making it more practical to scale up production and deploy these systems outside carefully controlled lab settings.

Why synthetic tendons matter beyond robotics

The impact of this work extends beyond the robots themselves. By showing that synthetic tendons can reliably couple living muscle to engineered structures, the MIT team has opened a path toward hybrid systems that blend biological and artificial components in more sophisticated ways. In prosthetics, for instance, tendon-like connectors could help integrate muscle grafts with mechanical limbs, potentially giving users more natural control and feedback. In tissue engineering, similar structures might anchor growing muscle to scaffolds that train it to contract in useful patterns, improving the quality of lab-grown meat or therapeutic implants.

There is also a conceptual shift at play. Instead of treating biology as a fragile add-on to conventional machines, the tendon framework treats muscle as a first-class actuator whose limitations can be engineered around with smart mechanics. That mindset could influence how researchers design everything from biohybrid drones to implantable pumps, encouraging them to think in terms of interfaces and transitions rather than simple substitutions of motors with cells. As reports on the MIT work make clear, once the tendon problem was addressed, the rest of the system fell into place, suggesting that similar interface-focused strategies might unlock comparable gains in other biohybrid technologies.

More from MorningOverview