Hospitals and public spaces are locked in a quiet arms race with microbes that cling to surfaces, shrug off disinfectants, and evolve around our best drugs. Now researchers are turning to a Nobel Prize-awarded material that does not poison bacteria but physically shreds them with microscopic knives built into the surface itself.

Instead of relying on antibiotics or chemical coatings that can fade or fuel resistance, this new approach uses engineered nanostructures to puncture bacterial cells on contact. I see it as part of a broader shift toward “mechanical immunity” in materials science, where the very texture of metals, coatings, and frameworks becomes a lethal landscape for microbes.

How a Nobel Prize material became a microscopic knife

The core of the story is a class of crystalline substances known as metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, which were originally celebrated for their ability to trap gases and enable water extraction from desert air. In work highlighted by Nov Nobel Prize New Researchers, scientists have now reimagined these structures as physical weapons against bacteria, sculpting them into sharp nanotips that jut from a surface like a bed of invisible needles. Instead of soaking microbes in toxins, the material turns every point of contact into a mechanical hazard that tears open cell walls.

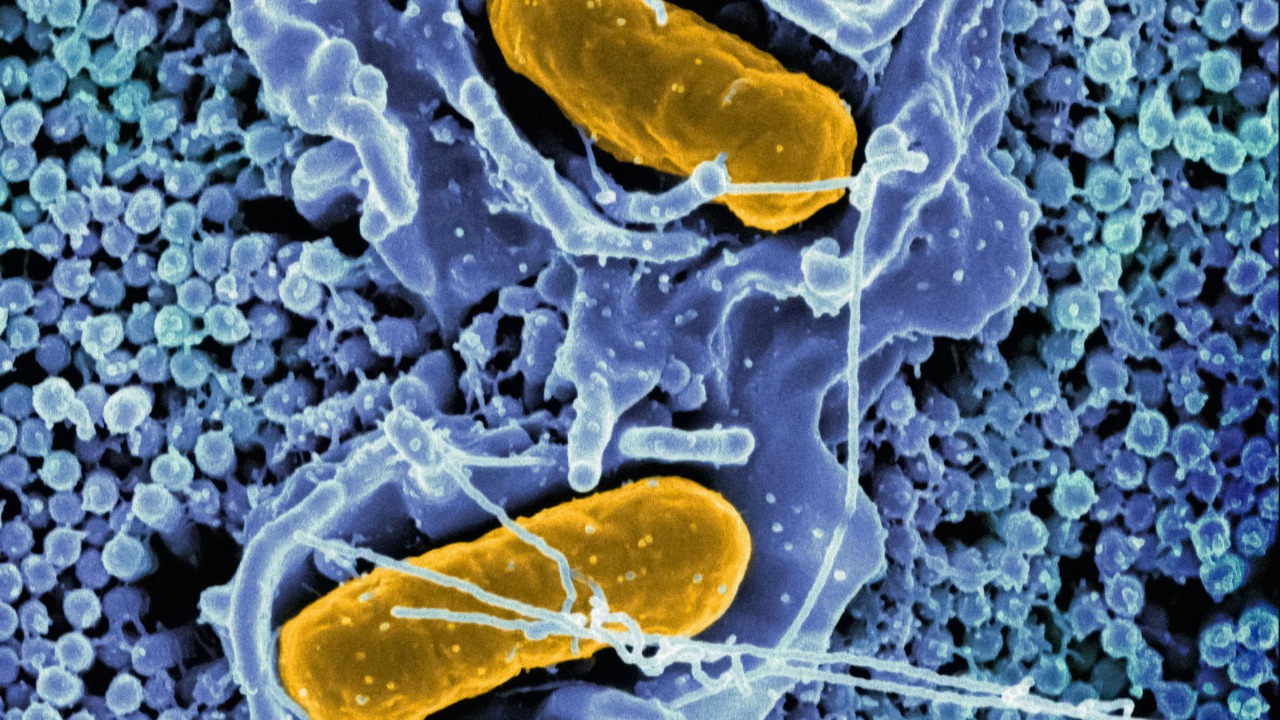

In laboratory images, the effect is brutally clear: scanning electron microscopy captures the moment a bacterium slumps and collapses as a MOF spike pierces its membrane. Reporting on this work describes how the MOF structure, when grown in the right way, forms a dense forest of nanoscale blades that puncture cells as they try to settle, effectively turning a once-neutral surface into a kill zone for microbes that might otherwise seed biofilms and fuel the development of antibiotic resistance, a process vividly illustrated in Dec MOF.

What “stabbing” bacteria really looks like at the nanoscale

At first glance, the idea that a solid material can “stab” bacteria sounds like science fiction, but at the nanoscale it is a straightforward matter of geometry and force. Bacterial cells are soft, pressurized sacs; when they land on a surface bristling with rigid spikes only a few tens of nanometers wide, their own weight and motion push the membrane onto those points until it ruptures. Coverage of this work has leaned into the visceral metaphor, describing how the new material “stabs and kills bacteria with microscopic knives” and emphasizing that, unlike traditional disinfectants, it does so without relying on toxins or antibiotics, a distinction captured in the phrase New Material Stabs and Kills Bacteria With Microscopic Knives, Yes, Really, Instead of.

What makes this approach so powerful is that the killing mechanism is purely physical, which means bacteria cannot easily adapt by tweaking a single gene or enzyme. To survive, they would need to fundamentally change their size, stiffness, or shape, a far taller evolutionary order than acquiring a resistance gene. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology have leaned into this advantage, refining the MOF growth process so that the crystals form sharp nanotips rather than blunt particles, and stressing that this is a Nov Nobel Prize New Researchers strategy that maximizes mechanical damage instead of chemical attack.

Why surface-borne bacteria are such a stubborn problem

The urgency behind these microscopic knives comes from a very practical headache: bacteria that multiply on surfaces are a major threat in healthcare, especially when they colonize implants, catheters, and other devices that stay inside the body. Once they gain a foothold, they can form slimy biofilms that shield them from disinfectants and immune cells, turning a routine procedure into a chronic infection risk. Reporting on the new MOF work underscores that Nov Bacteria that multiply on surfaces are not just a clinical nuisance but a significant economic burden, driving up treatment costs and hospital stays.

Traditional infection control leans heavily on antibiotics and chemical disinfectants, but both tools are under strain as resistance spreads and as regulators push to limit harsh chemicals in public environments. That is why I see mechanically active surfaces as more than a clever lab trick; they are a structural answer to a structural problem. If the surface of an implant or a hospital rail is inherently hostile to microbes, then every contact becomes a defensive act, not a new opportunity for contamination.

Graphene spikes and the rise of mechanical bactericides

The MOF breakthrough does not appear in isolation; it builds on a decade of work showing that sharp nanostructures can slice through microbes without any added drugs. Earlier research on graphene, a single-atom-thick form of carbon, demonstrated that when it is arranged into tiny spikes, it can kill bacteria on implants and stop infection by physically disrupting cell membranes. In one study, a textured coating of graphene was shown to create lethal “spikes” on medical hardware, with the authors describing how Apr Graphene Spikes Kill Bacteria Implants and Stop Infection Home Science Implants by turning otherwise smooth surfaces into jagged terrain at the nanoscale.

More recent work has refined this concept into engineered “nanospikes” that combine mechanical damage with oxidative stress, broadening the spectrum of bacteria that can be targeted. One detailed study reported a broad-spectrum bactericidal surface consisting of graphene nanospikes synthesized by plasma-enhanced methods, and concluded that Jan Herein graphene nanospikes exert bactericidal effect through mechanical damage and oxidative stress. I read the MOF work as the next logical step: instead of relying on a single material like graphene, researchers are now tapping a whole family of porous crystals that can be tuned, grown, and integrated into different devices while preserving that same lethal topography.

From implants to steel: building self-defending hardware

One of the most promising aspects of these microscopic knives is how easily the concept travels from one material to another. On implants, a tiny layer of graphene flakes has already been shown to become a deadly weapon against bacteria, with experiments demonstrating that a Apr Tiny layer of graphene flakes becomes deadly weapon against bacteria on implants by slicing into cells that try to adhere. That same logic is now being applied to metals used in everyday infrastructure, where the stakes are just as high but the design constraints are different.

Researchers working with stainless steel, for example, have shown that by modifying the surface at the micro and nanoscale, they can create textures that kill bacteria without antibiotics or chemicals. One group has argued that this modified stainless steel could save lives, pointing to a global study of drug-resistant infections that found they directly killed 1.27 m people in a single year and were associated with many more deaths. When I connect that figure to the rise of mechanically active surfaces, the appeal is obvious: if the metal in hospital beds, door handles, and transit poles can be engineered to quietly rupture bacteria on contact, then infection control becomes a property of the hardware itself, not just a protocol layered on top.

Paint, coatings, and the promise of contact killing

Not every surface can be rebuilt from scratch, which is why coatings and paints are emerging as a crucial bridge between lab science and real-world deployment. In one project, researchers collaborated with Indestructible Paint to create a prototype antimicrobial paint that activates upon drying and effectively kills a wide range of pathogens on contact. The team behind this work emphasized that the prototype coating, developed in collaboration with Indestructible Paint, was able to neutralize flu, MRSA, and COVID-19 on contact, hinting at how similar formulations might one day incorporate mechanical features like MOF nanotips or graphene spikes.

From my perspective, the key is that these coatings shift the burden from constant cleaning to passive defense. Instead of relying solely on staff to disinfect every surface on a strict schedule, a mechanically active paint or varnish could keep working between cleanings, slashing the number of viable microbes that survive long enough to spread. The MOF-based microscopic knives fit neatly into this vision: they can be embedded into thin films or composite layers, turning ordinary-looking walls, rails, or instrument casings into active participants in infection control rather than passive liabilities.

How contact-based killing changes the resistance equation

Behind the technical details lies a strategic shift in how I think about antimicrobial design. Traditional drugs work by interfering with specific biochemical pathways, which bacteria can often evade by mutating a protein or acquiring a resistance gene. In contrast, contact-based killing relies on physical interactions at the surface, where the antimicrobial action is purely mechanical and depends on factors such as surface charge, roughness, and geometry. A comprehensive review of these systems notes that This is a type of contact-based killing where the bactericidal effect is driven by the interface itself rather than by diffusing chemicals.

That distinction matters because it changes the evolutionary landscape for microbes. To escape a drug, a bacterium might only need a single mutation; to escape a forest of nanoscale knives, it would need to alter its entire physical architecture or avoid the surface altogether. MOF nanotips, graphene nanospikes, and textured steels all exploit this asymmetry, forcing bacteria into a corner where the cost of adaptation is high and the path to resistance is murky. I see this as a rare example in the antimicrobial field where the physics of the system, not just the chemistry, tilts the long-term odds in our favor.

Why MOFs are uniquely suited to the next generation of antimicrobial surfaces

Among the various materials vying for a role in this new landscape, MOFs stand out because of their tunability and pedigree. They are built from metal ions linked by organic molecules into highly porous, crystalline frameworks, and their inventors were honored with a Nobel Prize for opening up a new way to design materials atom by atom. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology have now taken that legacy in a new direction, describing a New Way Use Metal Organic Frameworks Researchers Chalmers University of Technology to puncture and kill bacteria by growing the crystals into sharp, vertically aligned structures that act as nanoscale spears.

Because MOFs can be synthesized with different metals and linkers, they offer a modular platform for tailoring both mechanical and chemical properties. A hospital might one day specify a MOF coating that combines physical stabbing with controlled release of a mild antiseptic, or a water treatment plant could deploy a MOF filter that both traps and ruptures microbes as they flow past. In that sense, the microscopic knives are not just a clever trick but a gateway to a broader class of “smart” surfaces, where the same material can be tuned for filtration, sensing, and antimicrobial defense depending on how it is grown and integrated.

The road from lab images to everyday protection

For all the striking microscopy and dramatic language about stabbing bacteria, the real test for these materials will be how they perform outside controlled experiments. Scaling up MOF nanotips or graphene spikes onto large, durable surfaces will require manufacturing methods that can reproduce nanoscale features over square meters of metal, plastic, or paint without losing sharpness or adhesion. Engineers will also need to ensure that these microscopic knives are safe for human contact, do not shed harmful particles, and can withstand cleaning, abrasion, and environmental wear over years of use.

Even with those challenges, I find the trajectory encouraging. The convergence of Nobel Prize-level chemistry, precision nanofabrication, and urgent public health needs has created a moment where materials that once seemed esoteric are being reimagined as frontline defenses against infection. If MOF-based microscopic knives and their graphene cousins can make the leap from lab benches to hospital wards, transit systems, and household products, they could quietly reshape the microbial landscape around us, turning everyday surfaces into active allies in the fight against bacteria rather than passive hosts.

More from MorningOverview