Nuclear rockets are moving from Cold War concept to near-term hardware, and the shift could reshape how quickly and safely humans cross the solar system. By pairing compact reactors with efficient propulsion systems, NASA and its partners are betting they can cut travel times, shrink fuel loads, and open deep space to routine exploration in a way chemical engines never could.

Why NASA is betting on nuclear propulsion now

I see NASA’s renewed push on nuclear propulsion as a response to a simple constraint: chemical rockets are reaching the practical limits of what they can do for long-duration crewed missions. Even the most advanced methane or hydrogen engines still demand huge propellant tanks and accept months-long transit times to Mars, which magnify radiation exposure, medical risk, and mission cost. To break that tradeoff, NASA is turning to space nuclear propulsion, which promises high thrust with far better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets.

At the core of this strategy is Nuclear Thermal Propulsion, often shortened to NTP, which uses a fission reactor to superheat propellant instead of relying on chemical combustion. According to NASA’s own technical overview, a Nuclear system can deliver roughly twice the propellant efficiency of chemical engines while still producing strong thrust, which means a spacecraft can carry less fuel, more payload, or both, and still accelerate harder. That combination of higher performance and reduced mass is why the agency now treats nuclear propulsion not as a far-off science project but as a key enabler for future human missions beyond low Earth orbit.

How Nuclear Thermal Propulsion actually works

To understand why Nuclear Thermal Propulsion is so central to NASA’s plans, it helps to look at how the technology functions. Instead of burning fuel and oxidizer together, an NTP engine runs a compact reactor that heats a lightweight propellant, typically liquid hydrogen, which then expands through a nozzle to create thrust. Because the energy comes from fission rather than chemical bonds, the exhaust velocity is much higher, which is what gives NTP its roughly twofold improvement in specific impulse over chemical systems and allows a vehicle to travel farther on the same propellant mass.

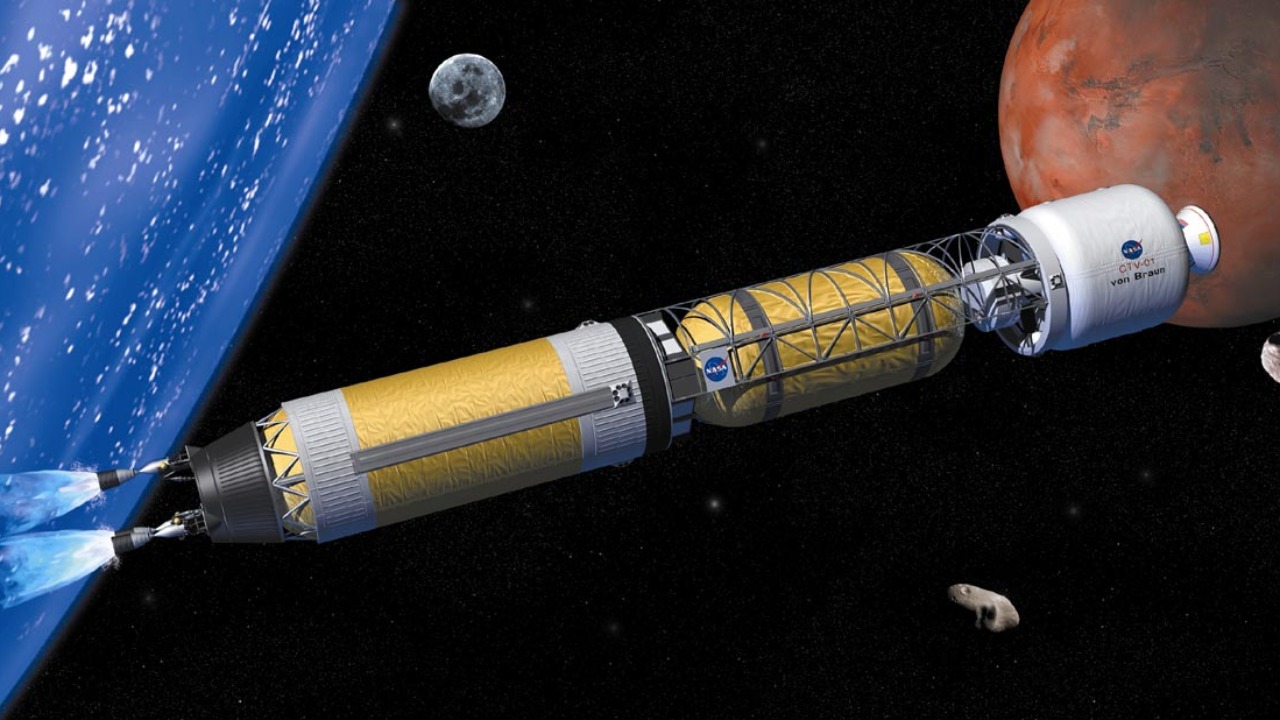

NASA has framed Nuclear Thermal Propulsion as “Game Changing Technology for Deep Space Exploration,” and that description is not hyperbole. The agency’s historical work traces back to the 1960s, when rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun championed nuclear stages for crewed Mars missions, but the current effort is more tightly focused on practical, testable hardware. In the modern architecture, the reactor core, control drums, and turbomachinery are designed to operate for limited, well-characterized burn periods, which lets engineers manage radiation, thermal loads, and structural stresses while still delivering the high thrust needed for rapid transits.

From Wernher’s vision to today’s test stands

When I look at the arc from Wernher von Braun’s early nuclear concepts to today’s test campaigns, the most striking change is how much closer the technology is to operational use. In the 1960s, nuclear rocket programs produced impressive ground tests but never flew, in part because the Apollo program’s success reduced the political urgency for more powerful engines. Now, with human missions to Mars back on the agenda and commercial partners building heavy-lift launchers, the case for a compact, high-performance upper stage has returned, and NASA is again investing in reactor materials, fuel elements, and engine cycles that can survive the brutal conditions inside an NTP core.

The agency’s current work on NTP reflects lessons learned from those earlier efforts. Engineers are focusing on fuel forms that can withstand extreme temperatures without cracking, control systems that can throttle the reactor safely, and test protocols that validate performance without releasing radioactive material into the environment. The Department of Energy is a central partner in this work, and reporting on the program notes that the Department of Energy sees NTP as a technology with “a great chance of exploring deep space,” a sign that the nuclear and space communities are more aligned than they were in the past.

Cutting the trip to Mars down to size

The most immediate payoff from nuclear propulsion would be on the route to Mars, where every week shaved off the journey reduces risk for astronauts. With chemical propulsion, a crewed mission typically faces months in transit each way, which compounds exposure to cosmic radiation and the physiological effects of microgravity. NTP engines, by contrast, can deliver higher average thrust and more efficient burns, which lets mission planners design trajectories that reach Mars faster while still preserving fuel margins and abort options.

That is not just a theoretical claim. Work at Oak Ridge National Laboratory has already demonstrated a novel nuclear rocket fuel that is being evaluated for NTP engines, and the lab’s analysis concludes that such engines could drastically reduce transit times to Mars while also cutting overall mission costs and the effects of radiation and zero gravity on astronauts. In practical terms, the NTP approach allows mission designers to trade some of the mass currently reserved for propellant into additional shielding, life support, or scientific payloads, all while shortening the time crews spend en route to and from Mars.

Nuclear Electric Propulsion and the long game

While NTP focuses on high thrust for relatively short burns, NASA is also advancing Nuclear Electric Propulsion, which uses a reactor to generate electricity that then powers high-efficiency electric thrusters. I see this as the long-game technology for cargo and deep-space science missions, where continuous low thrust over months or years can gradually build up enormous changes in velocity. For a crewed Mars mission, a hybrid architecture that uses NTP for departure and capture burns and Nuclear Electric Propulsion for in-space maneuvering could offer a powerful combination of speed and efficiency.

NASA’s Langley Research Center has highlighted how Nuclear Electric Propulsion technology could make missions to Mars faster by allowing planners to “tune” the trajectory over time instead of committing to a single impulsive burn. The center’s analysis notes that the trip to Mars and back is not one for the faint of heart, and that with electric propulsion powered by a reactor, engineers can “optimize it” by adjusting thrust profiles as conditions change. In practice, that means a Mars architecture where cargo ships depart early on efficient electric spirals while crewed vehicles follow later on faster NTP-assisted paths, all supported by the same family of nuclear power systems.

Balancing performance, safety, and public trust

Any time I talk to non-specialists about nuclear rockets, the first questions are about safety, not performance, and NASA’s program is clearly structured around that reality. For NTP, the reactor remains shut down until the vehicle is on a safe trajectory away from Earth, and the fuel elements are engineered to contain fission products even under severe thermal stress. On the ground, test campaigns are designed to validate materials and components without venting radioactive exhaust, which is one reason so much effort is going into non-nuclear testbeds and high-fidelity simulations before any full-power reactor firing.

Public trust also depends on clear roles and oversight, and here the partnership with the Department of Energy is central. The Department of Energy brings decades of experience in reactor safety, fuel fabrication, and waste handling, and its involvement in NTP is a signal that the program is being treated as a serious nuclear project, not just a propulsion experiment. For NASA, that collaboration is essential not only to meet regulatory requirements but also to reassure the public that the same rigor applied to terrestrial reactors is being brought to the engines that might one day power human crews to Mars and beyond.

Economic and mission design ripple effects

The economic implications of nuclear propulsion are as important as the physics. If a Nuclear system can deliver twice the propellant efficiency of chemical rockets while maintaining high thrust, as NASA’s space nuclear propulsion overview notes, then every kilogram launched from Earth can do more work. That translates into smaller upper stages, fewer tanker flights, or more ambitious payloads for the same launch mass, all of which feed directly into mission cost and feasibility. For a Mars campaign that might require multiple heavy-lift launches, shaving even a modest percentage off the total mass can save billions of dollars over the life of the program.

Mission design also changes when propulsion is no longer the tightest constraint. With NTP and Nuclear Electric Propulsion in the toolbox, planners can consider trajectories that were previously impractical, such as faster conjunction-class Mars missions, extended stays in high-radiation environments for science probes, or multi-target tours of the outer planets. The ability to carry more shielding or redundant systems without blowing the mass budget improves crew safety, while the option to redirect or retarget spacecraft mid-mission gives operators more flexibility to respond to new discoveries. In that sense, nuclear propulsion is not just a faster engine, it is a structural shift in how space agencies think about risk, redundancy, and return on investment.

What success would mean for deep space exploration

If NASA’s nuclear rocket push delivers on even part of its promise, the practical map of the solar system will look very different. Human missions to Mars would move from once-in-a-generation stunts to repeatable expeditions, with transit times short enough to make long surface stays more attractive than extended cruises in deep space. Cargo could be pre-positioned efficiently, scientific payloads could be larger and more capable, and the psychological barrier of months in transit would be lowered for astronauts and mission planners alike.

Beyond Mars, the same technologies could unlock missions that are barely sketches today. High-power Nuclear Electric Propulsion could send orbiters to Uranus and Neptune with enough propellant margin to tour multiple moons, while NTP stages might support rapid sample-return missions from the asteroid belt or the moons of Mars. For now, those scenarios remain on the drawing board, and many technical and political hurdles still stand between the current test campaigns and a flight-ready nuclear stage. But the direction of travel is clear: by investing in Nuclear Thermal Propulsion, Nuclear Electric Propulsion, and the supporting infrastructure, NASA is laying the groundwork for a future in which nuclear rockets are not exotic one-offs but standard tools for reaching the most distant corners of the solar system.

More from MorningOverview