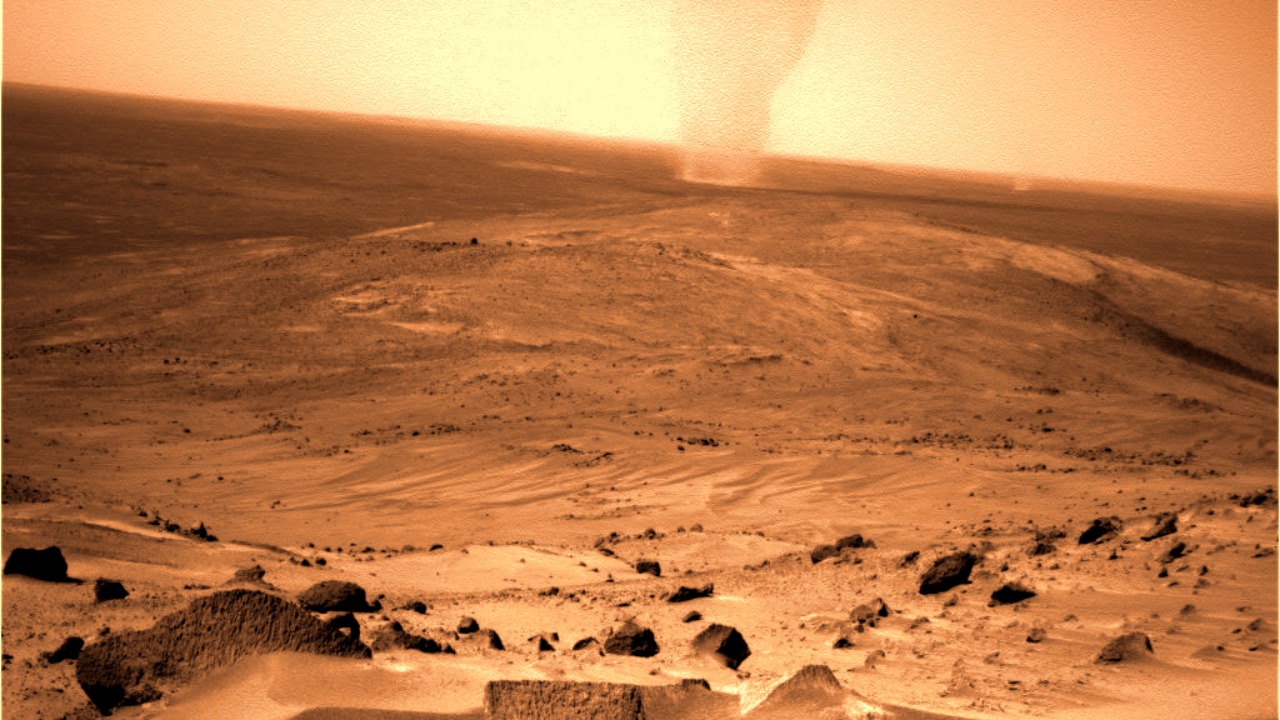

Mars has a new showpiece for planetary scientists, and it looks uncannily like a butterfly frozen mid-flight. A fresh set of images from a long-running European orbiter reveals an impact scar whose sweeping debris “wings” cut across the Red Planet’s ancient terrain, turning a violent collision into an unexpectedly delicate pattern. The shape is striking on its own, but the real story is how this crater’s odd geometry opens a window into Martian impacts, buried ice, and the planet’s restless volcanic past.

Instead of the neat circles that usually mark where space rocks slam into Mars, this feature stretches outward in asymmetric lobes that trace the path of material blasted from the ground. By unpacking how that butterfly-like pattern formed, researchers are piecing together a more detailed history of how impacts, lava flows, and possibly even water have sculpted the Martian surface over billions of years.

The orbiter that caught a butterfly in flight

The discovery is the latest reminder that some of the most transformative Martian science comes not from new spacecraft, but from veteran workhorses still circling the planet. The European Space Agency’s Mars Express mission has been orbiting Mars for years, yet it continues to deliver images that reframe how scientists think about the planet’s geology. Its cameras and spectrometers were designed to map the surface and atmosphere in detail, and that long baseline of observations is exactly what makes unusual features like this butterfly-shaped crater stand out. When you have seen thousands of ordinary impact scars, one that breaks the rules becomes impossible to ignore.

From my perspective, the longevity of Mars Express is part of what makes this find so compelling. Instead of a one-off snapshot, the orbiter can place the butterfly crater in a broader context, comparing it with other impact sites and tracking subtle changes in dust and frost over time. The mission’s sustained coverage has already helped researchers trace how impacts, volcanic flows, and erosion have reshaped the Martian surface over billions of years, and the butterfly crater now joins that catalog as a particularly vivid case study in how a single collision can interact with complex subsurface layers.

A Martian butterfly takes shape

At first glance, the feature looks almost whimsical, as if someone had pressed a butterfly stamp into the Martian crust. The European Space Agency leaned into that visual when it highlighted the scene under the playful banner of “A martian butterfly flaps its wings”, inviting viewers to puzzle over whether they were seeing an insect, a fossil, or even an eye before revealing the prosaic truth: it is an impact crater with an unusually sculpted ejecta blanket. The “body” is the central circular depression where the meteoroid slammed into the ground, while the “wings” are broad, asymmetric fans of debris that spread out on either side.

What makes this butterfly analogy more than a visual gimmick is the symmetry and reach of those wings. Instead of a simple ring of material around the crater, the ejecta stretches in elongated lobes that suggest the impactor struck at a shallow angle, flinging debris preferentially along its path. In planetary science, such low-angle impacts are prized because they encode information about the direction and speed of the incoming object, as well as the layering and strength of the surface it hit. Here, the butterfly shape acts like a frozen diagram of the collision, preserving clues about both the meteoroid and the Martian ground it disrupted.

Why this crater looks nothing like a neat circle

Most impact craters on Mars are nearly round, even when the meteoroid comes in at a slant, because the explosion of energy at the moment of impact tends to even out the shape. The butterfly crater breaks that pattern, and that is exactly why researchers see it as scientifically rich. According to analyses of the images, the impactor appears to have struck at a very low angle, so instead of ejecting material evenly in all directions, the blast carved out elongated “wings” of debris that stretch away from the central pit. The result is a crater that looks more like a stylized insect than a textbook circle, a reminder that geometry on Mars is often written by the angle of incoming rocks.

In my view, the irregularity of the wings is as important as their overall outline. One detailed description notes that, in this case, scientists would normally expect material to be thrown outward in a more symmetric pattern, yet here the ejecta is lopsided and the wings are irregular, a sign that the subsurface was anything but uniform. A closer look at the dazzling image shows that the debris fans are patchy and uneven, hinting at layers of rock, dust, and possibly ice that responded differently to the shock. That complexity is exactly what makes the crater a natural laboratory for understanding how Martian crust behaves under extreme stress.

Idaeus Fossae and the butterfly’s neighborhood

The butterfly crater does not sit in isolation. It lies in the Idaeus Fossae region, a landscape of fractures, valleys, and mesas that already tells a complicated geological story. The Mars Express orbiter captured a particularly striking view of this area, showing the butterfly-shaped crater in context with the surrounding terrain, where wing-like debris appears to unfurl across the surface. In that scene, Idaeus Fossae looks less like a static plain and more like a record of repeated upheavals, with the butterfly crater as one of the latest dramatic entries.

What stands out to me in the Idaeus Fossae images is how the butterfly’s wings drape over older features, almost like a fresh coat of paint on a weathered wall. A detailed perspective from the region, described as “The ‘butterfly crater’ of Idaeus Fossae on Mars”, highlights how the ejecta interacts with nearby Table mountains and other elevated structures. Those relationships help scientists work out which events came first, using the principle that younger deposits tend to lie on top of older ones. In Idaeus Fossae, the butterfly crater’s debris clearly overprints some features while being cut by others, turning the region into a layered puzzle of impacts and erosion.

Table mountains, mesas, and the story in the surrounding rock

Zooming out from the crater itself, the surrounding landscape is full of clues about the forces that have shaped this part of Mars. South of the butterfly crater, Table mountains and other elevated blocks rise from the plains, their flat tops and steep sides reminiscent of mesas in the American Southwest. These structures are not just scenic backdrops. They are remnants of older layers that have resisted erosion, standing as reference points against which newer features, like the butterfly’s wings, can be measured. When ejecta laps up against these mesas, it effectively timestamps the collision relative to the carving of the highlands.

Several other interesting surface features are also captured in the Mars Express imagery, and they help flesh out the environmental context. Around the crater rise steep slopes and isolated plateaus, described in one account as mesas that stand out clearly from the surrounding terrain, evidence of the erosional forces that once shaped this landscape. In that same analysis, the mesas are used to infer that a complex interplay of impacts and erosion existed when the collisions occurred, a point underscored in a report that notes how Several other interesting surface features frame the crater. To my eye, that interplay between the butterfly’s fresh-looking wings and the weathered mesas around them is what turns a pretty picture into a layered geological narrative.

Volcanic plains and a 45 km cousin in Hesperia Planum

The Idaeus Fossae butterfly is not the only Martian crater to earn that nickname, and comparing it with its relatives helps sharpen the science. In Hesperia Planum, another region of Mars shaped by ancient lava flows, Mars Express has imaged a large circular feature, partly cut off by the border of the frame, with a diameter of roughly 45 km. This structure also shows butterfly-like patterns in its ejecta, but it sits in a different geological setting, on plains that lie hundreds of metres below the surrounding highlands. That contrast in elevation and background rock gives scientists a chance to see how similar impacts play out in different environments.

From my standpoint, the Hesperia Planum example underscores how much the target surface matters. In that region, the plains are thought to be volcanic in origin, with lava flows that once flooded low-lying areas and later hardened into a relatively uniform layer. When an impact carved out the 45 km crater, it punched through those volcanic deposits, exposing deeper material and sending debris skimming across the plains. By comparing the butterfly-like ejecta there with the more irregular wings in Idaeus Fossae, researchers can tease apart how factors like rock type, layering, and surface slope influence the final shape of an impact scar.

Impact, volcanic activity, and hints of water

What elevates the Idaeus Fossae butterfly from a photogenic oddity to a serious scientific target is the way it ties together several key processes on Mars. Analyses of the crater and its surroundings suggest that the impact did more than just blast a hole in the ground. It appears to have interacted with layers shaped by volcanic activity and possibly even ice or ancient water-rich deposits. One detailed report notes that, unlike the circular craters commonly seen on Mars, this butterfly-shaped feature reveals information about impact dynamics, volcanic activity, and possible water, highlighting its significance for understanding Martian geology. That combination of clues is rare in a single site.

In my reading, the most intriguing aspect is how the ejecta seems to respond to hidden structures beneath the surface. The same report emphasizes that this discovery is important because it sheds light on the distribution of ejected material and what that distribution says about subsurface layers, including any volatile-rich zones that might once have held water or ice. By tying the butterfly crater to these deeper questions, scientists are effectively using it as a probe into the Martian crust, a way to sample buried history without drilling. The fact that this insight comes from a feature that also happens to look like a butterfly only adds to its appeal as a touchstone for public engagement and serious research alike.

How Mars Express keeps rewriting the Red Planet’s history

Behind the scenes of these striking images is a methodical mapping effort that has been unfolding for years. The Mars Express mission has systematically surveyed the planet’s surface, atmosphere, and subsurface, building a layered archive that scientists can mine whenever a new feature, like the butterfly crater, comes into focus. One account of the mission’s work notes that the orbiter has helped reveal how impacts, volcanic activity, and possible water have shaped Mars, and that its long-term observations are crucial for tracing how the surface has evolved over billions of years. That continuity is what allows researchers to connect a single crater to broader planetary trends.

From my perspective, Mars Express exemplifies the value of sticking with a mission long after the initial headlines fade. Using data from the orbiter’s High Resolution Stereo Camera, scientists can reconstruct the topography around the butterfly crater in three dimensions, measure the thickness of its ejecta, and compare it with other impact sites scattered across the Red Planet. A detailed description of the new view of Mars notes that the image, captured by the European Space Agency’s spacecraft, showcases a dramatic impact crater whose debris wings spread out like a butterfly in flight, and that those wings were mapped using stereo data from the camera. That kind of precision turns a pretty picture into a quantitative dataset, one that can be fed into models of impact physics and crustal structure.

Reading the Red Planet’s past in a single strange crater

In the end, what stays with me about the butterfly crater is how much planetary history is compressed into its delicate outline. The Idaeus Fossae setting, with its fractures, Table mountains, and layered mesas, tells of tectonic stretching and erosion. The butterfly’s asymmetric wings speak to a low-angle impact that plowed through those preexisting structures, scattering debris in patterns that betray hidden layers and perhaps even pockets of ancient ice. Nearby, the 45 km cousin in Hesperia Planum shows how similar physics plays out on volcanic plains, reinforcing the idea that Mars is a patchwork of terrains, each responding differently to the same cosmic blows.

As Mars Express continues to circle the Red Planet, I expect more such features to emerge from its data, each one a small but vivid chapter in a much longer story. The butterfly crater is a reminder that even after decades of exploration, Mars still has the capacity to surprise, not just with hints of water or traces of volcanic fire, but with shapes that resonate on a human level. A crater that looks like a butterfly is easy to share on social media, but behind that instant appeal lies a sophisticated investigation into impact dynamics, crustal layering, and the intertwined roles of lava and water in sculpting a world. For scientists and the rest of us alike, that is a powerful combination.

More from MorningOverview