On an external drive, the delete key is more of a suggestion than a final verdict. Files that appear to vanish from a USB stick, portable SSD, or backup hard drive often linger in the background, waiting for anyone with basic recovery tools to bring them back. If that device ever leaves your control, the gap between “looks empty” and “truly erased” can decide whether your old tax returns, medical scans, or client documents stay private.

To actually retire an external drive safely, I need to think less like a casual user and more like a data recovery lab. That means understanding how deletion really works, why different hardware demands different tactics, and which mix of overwriting, built‑in commands, and physical destruction will match the sensitivity of the information I am trying to protect.

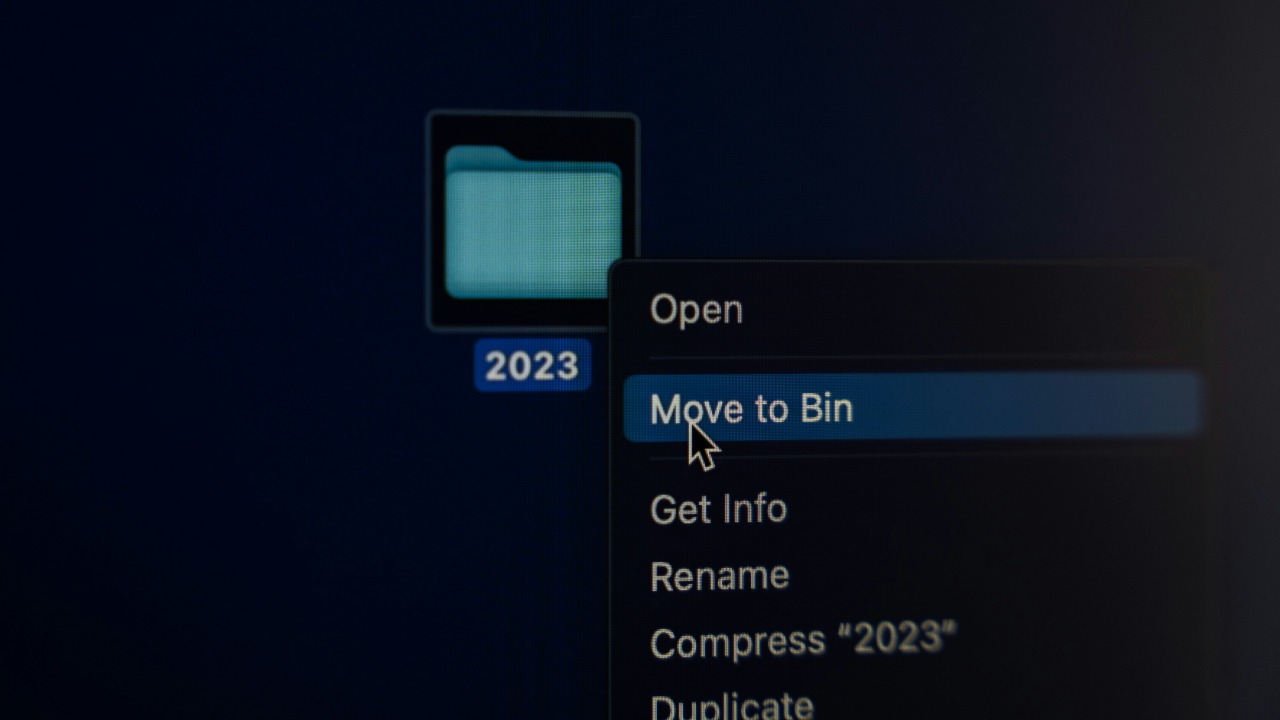

Why “delete” and “format” do not really erase an external drive

When I delete a file from an external drive, the operating system usually just removes its entry from the file system index and marks the space as available, it does not immediately overwrite the underlying bits. Dell’s own Deleting guidance explains that removing files from a hard drive simply reassigns that space so new data can be written later, which means the original content can still be recovered until it is overwritten. The same logic applies when I run a quick format on a portable HDD or flash drive, the structure that tells the system where everything lives is reset, but the actual sectors often remain intact.

That gap between logical deletion and physical erasure is exactly what recovery tools exploit. A Microsoft community answer on making files unrecoverable notes that even after I empty the recycle bin, specialized software can still scan the disk surface and reconstruct “deleted” content unless I use stronger Remember style deletion methods for sensitive information. On a Western Digital external drive, one Tom’s Hardware contributor bluntly confirms that a simple format will not delete the data and that it “should not be that hard” to recover, which is why they advise writing over each Hey sector of the drive individually if I want the contents gone.

How different drive types change the rules of erasure

The right way to wipe an external drive depends heavily on what is inside the enclosure. A Super User thread on reinstalling Linux from a USB stick spells this out clearly, the best way to wipe a drive depends on the drive type, because spinning hard disks, SATA SSDs, and NVMe sticks all manage data differently. Professional wiping services echo that point, explaining that Different storage technologies require specific wiping methods, with SSDs relying on specialized sanitization commands while traditional drives respond well to bulk overwriting.

On older or purely mechanical external HDDs, overwriting every sector is usually enough to defeat all but the most exotic lab work. For flash‑based devices, the picture is more complicated because of wear leveling and controller logic that can move data around behind the scenes. A technical brief on secure deletion warns that data can persist on magnetic disks, solid‑state devices, and flash media long after I think I have removed it, which is why it urges me to match my approach to Your security needs and the specific device in front of me. In practice, that means I should not assume a one‑click solution on a USB SSD will behave the same way as a multi‑pass wipe on a 3.5‑inch backup drive.

Overwriting: the core technique that actually removes data

Once I accept that deletion is mostly bookkeeping, overwriting becomes the central tool for real erasure. Data destruction specialists describe overwriting, also called disk wiping, as One of the most commonly used methods for erasing hard drive data, because it replaces existing information with new patterns to render the original content unrecoverable. Recycling firms that handle discarded computers say the same thing in plainer language, describing Overwriting as the most common method of data erasure, where the old bits are replaced with random data or zeros to make recovery more challenging or effectively impossible.

For external drives, that can mean running a full‑disk wipe utility that writes zeros or random data across the entire volume, not just the files I remember storing there. A detailed analysis of overwriting rounds notes that the safest and most cost‑effective way to make data disappear without destroying the disk is simply to overwrite it, then asks how many passes are really needed before a hard drive is completely wiped, a question that modern research answers with far fewer passes than older folklore suggested, especially when I follow a verified But standard. For most home users, a single thorough pass on a conventional external HDD is enough to defeat consumer recovery tools, while higher‑risk scenarios might justify multiple passes or a combination of wiping and physical damage.

Why specialized tools beat ad‑hoc tricks

Trying to improvise a secure wipe with random file copies or half‑understood commands is a good way to waste time and still leave traces behind. A Microsoft Windows 11 support thread on external drives spells out the difference, explaining that Unlike simple deletion, which only removes the file’s index entry, wiping actively replaces the data on the disk to make recovery far harder. That is why the same community that warns about recoverable deletions also recommends dedicated utilities that are designed to overwrite file data and make it unrecoverable, instead of relying on the operating system’s default delete behavior.

On the open‑source side, one of the best known tools is DBAN, a bootable environment built specifically to wipe disks by writing over them repeatedly. Super User contributors discussing how to permanently delete files from a flash drive point out that You could DBAN it, shorthand for using that utility to scrub the entire device. The project’s own site describes how DBAN automates multi‑pass overwrites across a drive, which is far more systematic than dragging a few dummy files into a folder and hoping for the best. For anyone preparing to sell or recycle an external HDD, a professional guide on secure disposal calls full‑disk overwriting the most reliable way to sanitize a drive so that even advanced forensic laboratories cannot recover the original data, provided I let the process complete across the entire Securely Wipe surface.

HDDs, SSDs, and flash sticks: how TRIM and wear leveling change the game

External hard drives that use spinning platters behave predictably when I overwrite them, but flash‑based devices add a layer of complexity. A technical note on secure deletion emphasizes that flash media and SSDs can retain data in unexpected places because of controller behavior and spare blocks, which is why it warns that sensitive information can remain on these devices long after deletion. At the same time, modern SSDs support TRIM and garbage collection, which can aggressively clear deleted blocks in the background, sometimes making traditional file recovery much harder than on an HDD.

One deep dive into flash behavior explains that In the past, I might have had a brief window before TRIM was executed, but on modern, healthy SSDs the command is often triggered so quickly that deleted data is destroyed almost before I finish clicking “Yes.” That sounds reassuring, yet it also means I cannot rely on old HDD‑style wiping tricks that assume a one‑to‑one mapping between logical sectors and physical cells. A separate industry blog on test equipment underlines that, as with an HDD or SSD, the only effective method to safely remove data is a complete overwrite of the media, which in the SSD world often means using built‑in secure erase or sanitize commands that instruct the controller to purge every cell, not just the ones the file system can see.

When overwriting is not enough: physical destruction and its limits

For highly sensitive data, especially in corporate or government settings, software wiping is often paired with physical destruction of the external drive. A step‑by‑step guide to secure destruction notes that once I have identified the drive type, the next move is to choose a method that matches how sensitive the data is and how much security I need, whether that is shredding, crushing, or degaussing, all of which are framed as options Now that the logical erasure is complete. Another breakdown of destruction methods lists shredding, crushing, and melting as ways to render platters and chips unreadable, but still treats overwriting as the first line of defense because it is designed to render the original data unrecoverable before any physical process begins.

Even then, the folk remedies that circulate online rarely hold up. An e‑waste specialist warns that Even throwing the drive in water or exposing it to fire may not completely destroy the data, because the platters or memory chips can sometimes be salvaged and read with the right equipment. That is why professional destruction services use industrial shredders, hydraulic presses, or certified degaussers rather than a hammer and a bucket. For a home user retiring an old external HDD that once held tax records, a thorough overwrite followed by drilling through the platters is usually enough, but for a company decommissioning drives with regulated health or financial data, policy often requires documented wiping plus certified destruction.

Real‑world habits: what users actually do before selling a drive

In practice, many people still treat external drives like disposable USB sticks, wiping them with a quick format and calling it a day. A Reddit Nov Comments Section on the best way to erase a hard drive before getting rid of it captures that tension, with some users insisting a single overwrite is enough for an HDD and others pointing out that the original poster asked about a hard disk, not an SSD, so the advice needs to match the hardware. That back‑and‑forth reflects a broader confusion, people know they should do “something more” than delete, but they are not always sure what that something should be.

Vendor forums show the same pattern. On Tom’s Hardware, a support rep opens with “You are right that a simple format won’t delete the data,” then walks the user through sector‑by‑sector overwriting as the only way to make recovery difficult. That kind of exchange underlines a basic reality, the tools and knowledge to wipe drives properly are widely available, but unless I deliberately seek them out, the default workflow on Windows, macOS, or a smart TV will leave a surprising amount of information behind on any external device I plug in.

How to choose the right erasure strategy for your external drive

For most people, the safest approach is to start by mapping the sensitivity of the data against the type of external drive they are dealing with. A technical paper on secure deletion advises me to think carefully about who and what I am trying to protect myself against, then choose the best wiping method accordingly, because casual thieves, targeted attackers, and forensic labs represent very different threat models for the same security needs. If I am donating a family backup drive that only ever held vacation photos, a single full‑disk overwrite with a trusted tool is usually enough. If that same drive once stored client legal files or medical records, I should be thinking in terms of certified wiping plus physical destruction.

Professional guidance on preparing drives for resale reinforces that logic, stressing that the most reliable way to sanitize a hard drive before selling or recycling it is a complete overwrite of the media, which is designed to defeat even the most advanced forensic Hard Drive Before Selling labs. For SSD‑based externals, I should look for manufacturer tools that trigger secure erase or sanitize commands, then, if the data is extremely sensitive, follow up with physical destruction. Across all of these scenarios, the pattern is the same, simply deleting files or formatting the drive is a cosmetic change, while real privacy depends on overwriting, hardware‑level erasure, or, when the stakes are high enough, turning the drive itself into scrap.

More from MorningOverview