Elon Musk’s rapidly expanding satellite fleets are colliding with one of the most delicate frontiers in science: the effort to capture fleeting, once-in-a-lifetime events in the distant universe. Astronomers now warn that a crucial space mission designed to catch these cosmic flashes could be compromised just as it is poised to deliver its most important discoveries.

What began as a debate over streaked night-sky photos has hardened into a broader alarm about whether low Earth orbit is being turned into a toll road that scientific missions must somehow navigate. I see a growing consensus among researchers that the scale and speed of these deployments, especially from Starlink, are outpacing the safeguards needed to protect billion‑dollar observatories and the fragile data they collect.

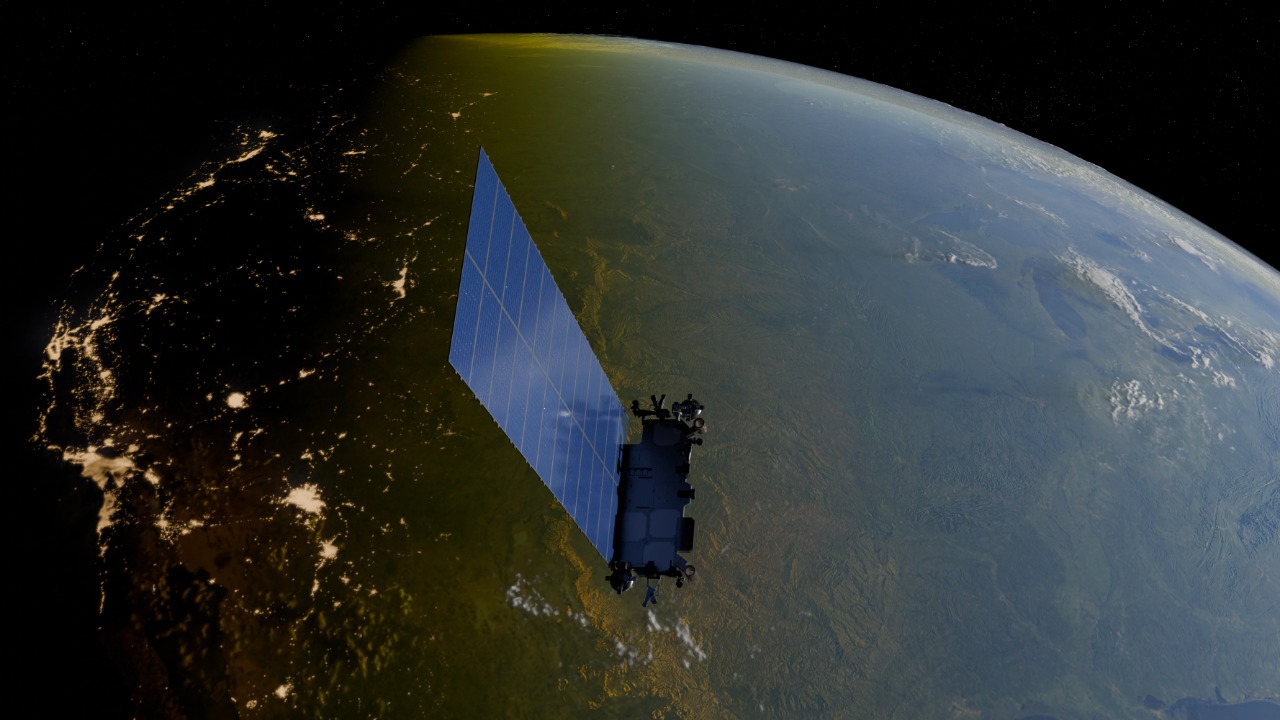

The new satellite surge and why astronomers are alarmed

The core concern is no longer a handful of bright objects gliding across long-exposure images, but a structural change in the sky itself. Planned constellations are so numerous that astronomers now talk about a permanent layer of moving hardware that scientific instruments must look through, a layer that can spoil data, blind sensors, or simply erase the rare signals that missions are built to find.

That shift is quantified in a recent analysis that simulated how future constellations would affect ground-based observatories. The study found that satellite swarms could photobomb more than 95% of some telescopes’ images, a figure that turns a nuisance into a systemic threat. When nearly every frame is at risk of contamination, the question becomes whether certain kinds of astronomy can still be done from Earth at all.

A crucial mission built to chase cosmic flashes

At the heart of the current warning is a class of missions that depend on speed and clarity rather than sheer collecting power. These observatories are designed to catch sudden, violent events such as supernovae or the brief explosions called γ‑ray bursts, which can fade in minutes. If a satellite crosses the field of view at the wrong moment, the event is not just degraded, it is effectively lost forever.

Researchers who modeled the impact of future constellations on these time‑critical observations simulated roughly 18,000 such γ‑ray bursts to see how often satellites would intrude. Their conclusion was stark: as the number of spacecraft grows, the odds that a crucial burst will be obscured at the exact moment it needs to be measured rise sharply, turning what should be a clean detection into a corrupted or unusable dataset.

Experts say Elon Musk’s satellites pose a direct threat

That abstract risk has now been tied directly to the hardware launched by Elon Musk. In recent days, a group of specialists has publicly argued that the satellites associated with Musk’s ventures are not just a general annoyance but a major threat to a specific, high‑value mission that depends on unobstructed views of these transient events. Their concern is not ideological; it is rooted in the geometry of orbits and the unforgiving timing of astrophysical flashes.

These Experts describe a pending orbital traffic jam in which the mission’s line of sight is repeatedly obscured by passing Starlink satellites, each one capable of blocking or distorting the signal from a target at the critical instant. One scientist put it bluntly, saying they “couldn’t be more concerned” about the way this congestion could undermine the mission’s core science goals.

NASA’s warning: a “toll road” in low Earth orbit

Inside NASA, the tone has shifted from quiet technical memos to more explicit warnings about what is at stake. Agency officials now describe a scientific enterprise under siege from multiple directions, with low Earth orbit filling up so quickly that every new mission must factor in the risk of interference from commercial constellations. The language has grown sharper as the potential cost to flagship observatories becomes clearer.

In one detailed assessment, NASA raised concerns that the growing density of spacecraft could jeopardize irreplaceable, time‑sensitive missions and even described the emerging environment as a kind of LEO toll road. The agency estimates that with the current trajectory of deployments, the cumulative impact on Earth‑observing and astrophysics missions could rise to the level of an existential threat to Earth science, forcing hard choices about which observations are still feasible.

Hubble as a cautionary tale for the next mission

The Hubble Space Telescope, long a symbol of what space science can achieve, has become a case study in how vulnerable even the most established observatories are to this new orbital reality. Hubble was never designed to peer through a sky crisscrossed by thousands of bright, fast‑moving satellites, yet that is increasingly the environment it must operate in. Each streak across its images represents lost exposure time and, in some cases, compromised science.

NASA has now warned that spacecraft launched by Elon Musk’s SpaceX are directly affecting Hubble’s work. Each Launched satellite has the potential to disrupt astronomy through both radio emissions and reflected sunlight, and the agency has flagged the telescope as being in the crosshairs of this interference. For the new mission focused on transient events, Hubble’s experience is a warning: if a billion‑dollar, long‑established observatory can be hampered this way, a fresh mission with even tighter timing requirements is at even greater risk.

How megaconstellations contaminate the data

From a technical standpoint, the problem is not just that satellites are visible, but that they inject structured noise into images and radio measurements that is hard to remove. A single bright trail can saturate detector pixels, leaving behind residual artifacts that algorithms struggle to clean. For missions chasing faint, distant signals, those artifacts can be indistinguishable from the very phenomena scientists are trying to measure.

The recent modeling of future constellations shows how severe this contamination could become. The study found that Now, with the immense number of satellites planned for orbit, some space telescopes could see up to one third of their images tainted. When that level of interference is combined with the finding that more than 95% of certain ground‑based images could be affected, it becomes clear that the contamination is not a marginal issue but a defining constraint on how future missions are designed.

The stakes for time‑sensitive, “irreplaceable” observations

What makes the current situation so fraught is that the mission under threat is not collecting routine survey data that can be reacquired later. It is chasing events that occur without warning and never repeat, from the collapse of massive stars to the mergers of neutron stars that forge heavy elements. If a satellite blocks the view at the wrong instant, the universe does not offer a second chance.

NASA has explicitly described these kinds of observations as irreplaceable and time‑sensitive, a category that includes the γ‑ray bursts used to probe the early universe and test fundamental physics. When I look at the combination of that fragility and the projected density of satellites, the risk calculus shifts: it is not just about lost observing efficiency, but about entire classes of discovery that could be foreclosed if the mission’s field of view is repeatedly compromised.

What mitigation looks like, and why it may not be enough

Satellite operators often point to mitigation measures such as darker coatings, adjusted orientations, and coordination with observatories to avoid the most sensitive observations. Those steps can help, and astronomers have acknowledged improvements in some newer spacecraft designs. Yet the sheer number of satellites planned means that even dimmer objects, multiplied by tens of thousands, still add up to a crowded and noisy sky.

The modeling behind the 95% contamination figure assumes that operators follow through on some of these mitigation strategies, yet the simulations still show a sky in which the mission’s detectors are almost never free of passing hardware. When I weigh that against NASA’s description of low Earth orbit as a toll road, it is hard to escape the conclusion that voluntary measures alone are unlikely to preserve the clean observing windows that this mission requires.

A turning point for how we govern the sky

The clash between Elon Musk’s satellite ambitions and a crucial scientific mission is more than a technical dispute; it is a test of how society values shared access to the sky. Low Earth orbit has been treated as a largely open frontier, where speed and capital determine who occupies which altitudes. The emerging science on contamination and interference suggests that this laissez‑faire approach is reaching its limits.

As astronomers tally up the projected loss of data, from Hubble’s streaked images to the simulated γ‑ray bursts that would be missed, the pressure is building for clearer rules on how many satellites can occupy a given shell, how bright they can be, and how they must coordinate with time‑critical missions. Whether regulators move in time will determine if the mission now in the crosshairs can fulfill its promise, or if its most important discoveries will be sacrificed to a sky increasingly dominated by commercial constellations.

More from MorningOverview