The universe’s expansion rate was supposed to be a solved problem, yet the latest high precision map of the early cosmos has pushed one of modern astronomy’s sharpest conflicts back to center stage. Instead of smoothing over the long running mismatch between different measurements of how fast space is stretching, the new data sharpen that discrepancy and force cosmologists to confront the possibility that something in their standard picture is missing.

At stake is more than a single number on a chalkboard, because the expansion rate sets the age, size, and ultimate fate of the cosmos, and it anchors how I interpret everything from nearby exploding stars to the faint afterglow of the Big Bang. The revived puzzle, widely known as the Hubble tension, now rests on a clash between exquisitely detailed maps of the infant universe and equally meticulous surveys of the modern one, with no obvious error bar big enough to make the two views line up.

What astronomers mean by “Hubble tension”

When cosmologists talk about the Hubble tension, they are really talking about two incompatible answers to a basic question: how many kilometers per second does the universe’s expansion speed up for every megaparsec of distance. Local measurements that build a “cosmic distance ladder” from nearby stars to faraway galaxies consistently land on a higher value, while early universe measurements that read subtle patterns in ancient light prefer a lower one, and the gap between them is now too large to dismiss as a statistical fluke.

On the local side, the Hubble Space Telescope has played a starring role, with one widely cited analysis finding a Hubble constant of 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec, or about 46 miles per second per megaparsec, for the current expansion rate of the universe. That figure sits uncomfortably above the roughly 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec preferred by early universe probes, and the mismatch is large enough that simply tweaking measurement techniques no longer looks like an easy way out.

How the new ACT map tightens the early universe side

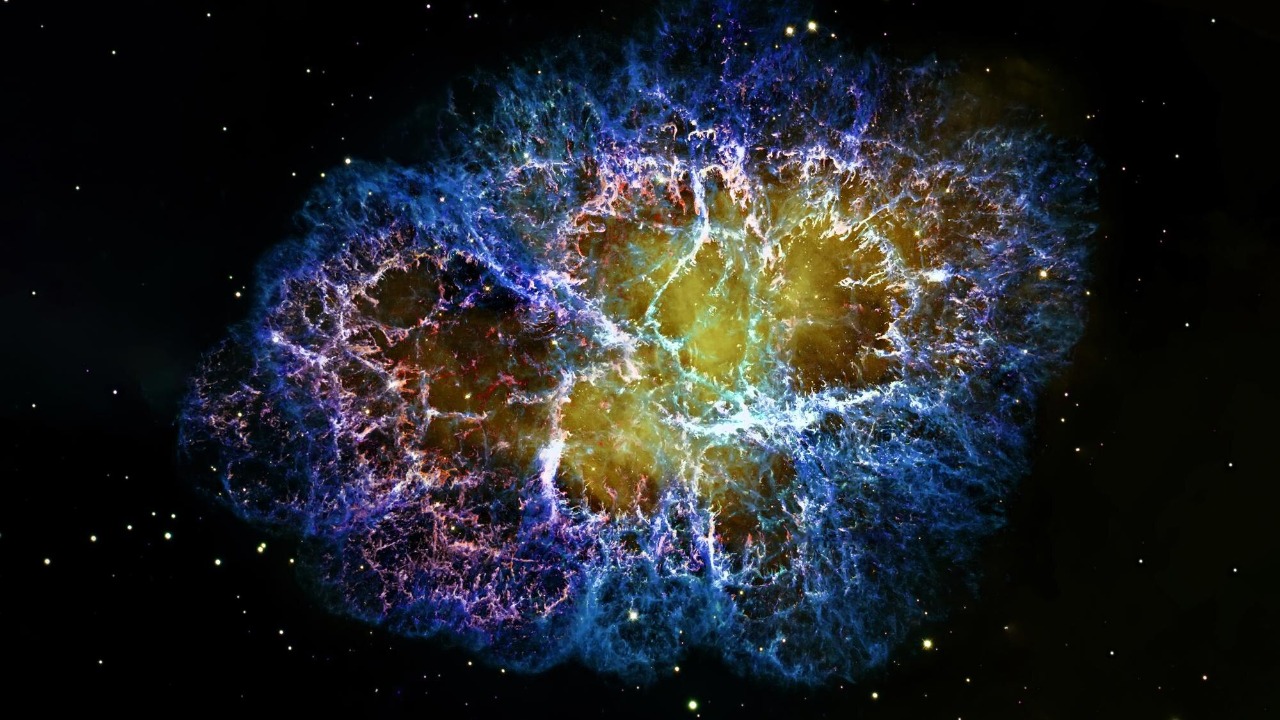

The latest twist comes from the final data release of the Atacama Cosmology Telescope, or ACT, which has spent years mapping tiny temperature variations in the cosmic microwave background across large swaths of sky. Those ripples, frozen into place when the universe was just a few hundred thousand years old, encode how much matter and energy filled space and how quickly it was expanding at that time, letting researchers infer what the Hubble constant should be today if the standard cosmological model is correct.

By combining ACT data with large scale information from WMAP, one analysis measured a Hubble constant of 67.6 plus or minus 1.1 km per second per Mpc at 68% confidence, squarely in line with earlier cosmic microwave background results. Earlier maps of this ancient light had gaps in their sky coverage, and However, the new ACT release fills many of those blind spots, which means the early universe estimate is now both more precise and more robust, and it still refuses to budge toward the higher local value.

Why Webb and Hubble have strengthened the local measurements

On the other side of the ledger, the case for a faster present day expansion has only grown stronger as new observatories have joined the effort. Astronomers use a chain of overlapping techniques, from pulsating stars in nearby galaxies to type Ia supernovae in the distant universe, to build a distance ladder that converts redshifts into an expansion rate, and each rung of that ladder has been scrutinized for hidden biases that might artificially inflate the Hubble constant.

Recent work that cross checks the distance ladder with both the James Webb Space Telescope and the NASA flagship Hubble has found that the two instruments agree on the key calibrations that feed into the local expansion rate. With both telescopes confirming each other’s findings, the argument that the Hubble tension is just a measurement glitch has become harder to sustain, and the higher local value now looks like a genuine feature of the data rather than an artifact of a single observatory.

Standard cosmology under pressure from both ends

The standard cosmological model, often called Lambda cold dark matter, was built to reconcile a wide range of observations with a simple recipe of dark energy, dark matter, and ordinary matter. For years it seemed to pass every test, from the pattern of galaxies on large scales to the detailed shape of the cosmic microwave background power spectrum, but the Hubble tension has turned into a stress test that the model is struggling to pass without modification.

Analyses that start from the early universe side, using the acoustic scale imprinted in the primordial plasma as a ruler, naturally land on a lower Hubble constant, while those that begin with nearby supernovae and other local tracers insist on a higher one, and as one detailed review put it, But if you instead begin with a signal imprinted onto the cosmos in the early Universe, the inferred expansion rate simply does not match the value derived from the distance ladder. That persistent mismatch has pushed theorists to ask whether the ingredients of the standard model are complete, or whether the behavior of dark energy, dark matter, or gravity itself might need to be revised.

New galaxy maps and the limits of statistical fixes

One natural hope was that better maps of the large scale structure of galaxies would reveal subtle selection effects or cosmic variance that could ease the tension. If, for example, we happened to live in an unusually underdense region of space, local measurements might be biased high relative to the cosmic average, and more comprehensive surveys could expose that quirk and bring the numbers into alignment.

Instead, new work that charts how galaxies cluster across vast volumes has tended to reinforce the idea that the two main approaches to measuring the expansion rate simply do not overlap within each other’s error bars. As one analysis of a new galaxy map put it, in an attempt to resolve the Hubble tension, numerous large international research teams have launched studies, yet the different determinations of the Hubble constant still fail to agree within the quoted uncertainties of each method. That outcome has shifted the conversation away from purely statistical explanations and toward the possibility that the underlying physics might be more complex than the standard model assumes.

Exotic fixes: rotating universes and giant voids

As the conventional options narrow, some researchers have turned to more exotic ideas that would have sounded speculative a decade ago. One line of work explores whether the cosmos might have a tiny global rotation, a slow spin that would be almost impossible to detect directly but could subtly alter how structures grow and how light propagates over billions of years, potentially affecting the inferred expansion rate.

In one such model, the Their calculations suggest the universe could rotate once every 500 billion years, a period so long that the spin would be far too slow to spot in everyday observations yet still enough to affect why measurements of cosmic expansion and structure growth do not quite agree. A related proposal, popularized in a short explainer that asks whether we might live in a giant underdense region, argues that a large local void could also help reconcile the numbers, and one video on the topic notes that there is a problem with measuring the expansion rate of the universe that is called the Hubble tension, though such void models face their own challenges in matching the full suite of data.

Dark energy, dark matter, and evolving ingredients

Other attempts to resolve the conflict focus less on geometry and more on the properties of the dark components that dominate the cosmic energy budget. In the standard picture, dark energy is a constant vacuum energy that accelerates the expansion at late times, while dark matter is a cold, collisionless substance that clumps under gravity but does not interact with light, and both are assumed to be stable and unchanging over cosmic history.

Some theorists have suggested that relaxing those assumptions could ease the Hubble tension, for example by allowing dark matter to slowly evolve or interact in ways that change the expansion history without spoiling the success of early universe fits. One analysis framed the issue bluntly, noting that for a while now there has been a problematic mystery at the heart of the standard cosmological model, and asking whether Although dark matter might be evolving over time instead of dark energy being the only driver of acceleration. In that view, the discrepancy between early and late measurements could be a clue that one of these invisible ingredients is not as simple as the textbook version suggests.

Supernovae, distance ladders, and the role of dark energy

The original discovery of cosmic acceleration came from type Ia supernovae, which serve as standardizable candles for mapping distances across billions of light years. Those same explosions now sit at the heart of the local expansion rate measurements, so any attempt to blame the Hubble tension on new physics must also preserve the success of supernova based evidence for dark energy, a constraint that has ruled out some of the more radical alternatives.

Detailed studies of these events find that the supernovae all fall along the line that the standard cosmological model predicts, even for the highest redshift explosions, which means any new ingredient must leave that relationship intact while still altering the inferred Hubble constant. As one discussion of the link between the Hubble tension and dark energy put it, the supernovae data show that error control is of paramount importance, yet Oct analyses still leave room for the possibility that the property you measured nearby is not identical to the one that governed the early universe. That subtle distinction keeps the door open for models where dark energy or gravity evolves just enough to shift the expansion rate without wrecking the supernova fit.

Alternative cosmic blueprints and the Planck benchmark

Any proposed solution also has to reckon with the extraordinary success of the cosmic microwave background as a blueprint for the early universe. The temperature and polarization patterns in that ancient light, mapped in detail by missions like the ESA Planck satellite, provide a snapshot of the cosmos when it cooled down from the Big Bang, and they have been the foundation for the lower Hubble constant that clashes with local measurements.

Those observations, which trace how sound waves propagated through the hot plasma of the young universe, have been used to pin down the densities of matter and radiation and to test alternative cosmological models that might ease the Hubble tension. As one summary of the early universe constraints notes, these observations were made by the ESA Planck satellite’s mapping of the cosmic microwave background radiation, which serves as a blueprint for the universe when it cooled down from the Big Bang. Any new physics that aims to raise the early universe Hubble constant toward the local value must thread a narrow needle, preserving that blueprint’s remarkable agreement with many other observations while still shifting the inferred expansion rate.

Why the puzzle matters for the future of cosmology

For now, the Hubble tension remains unresolved, and the new ACT map has made it harder to imagine that the problem will simply fade away as more data arrive. Instead, each new high precision measurement seems to deepen the puzzle, forcing cosmologists to weigh whether they are missing a subtle systematic error in one of their flagship techniques or whether the universe is quietly signaling that the standard model is incomplete.

Some speculative ideas, such as a universe that may revolve once every 500 billion years, highlight just how far theorists are willing to stretch in search of an answer, while more conservative tweaks to dark matter or dark energy try to preserve as much of the existing framework as possible. Either way, the revived tension has turned a once routine cosmological parameter into a potential gateway to new physics, and the next generation of surveys and telescopes will be judged in part by whether they can finally tell us which side of the cosmic map is right.

More from MorningOverview