The race to build lighter, more powerful electric motors has just produced a startling new benchmark: an in-wheel drive unit that delivers 1,000 hp per corner in a package small enough to disappear behind a brake disc. Instead of a bulky central motor and heavy driveline, this prototype tucks record power density directly into each wheel, promising supercar performance with less mass and more control. If it scales, the technology could reshape how electric cars are packaged, driven, and even braked.

At the center of this leap is Oxfordshire-based YASA, a specialist in axial flux motors that has already pushed power-per-kilogram figures far beyond conventional radial designs. By combining its compact motor with a tightly integrated in-wheel powertrain, the company is not just chasing headline numbers, it is testing a new architecture that could cut hardware, sharpen handling, and extend range all at once.

How YASA turned axial flux theory into a 1,000 hp wheel unit

The core breakthrough sits in the motor topology itself. Instead of the familiar cylindrical radial flux layout used in most EVs, YASA relies on an axial flux design that sandwiches a thin rotor between stator discs, which shortens the magnetic path and allows more torque from a smaller, flatter package. Earlier work from Yasa showed how far this could go, with a compact unit that delivered a 1,000-HP output while weighing less than 30 pounds, a figure that already put traditional EV motors on notice. That same philosophy now underpins the in-wheel prototype, which uses a similar axial layout to cram extraordinary power into a housing that can live inside a road car’s wheel.

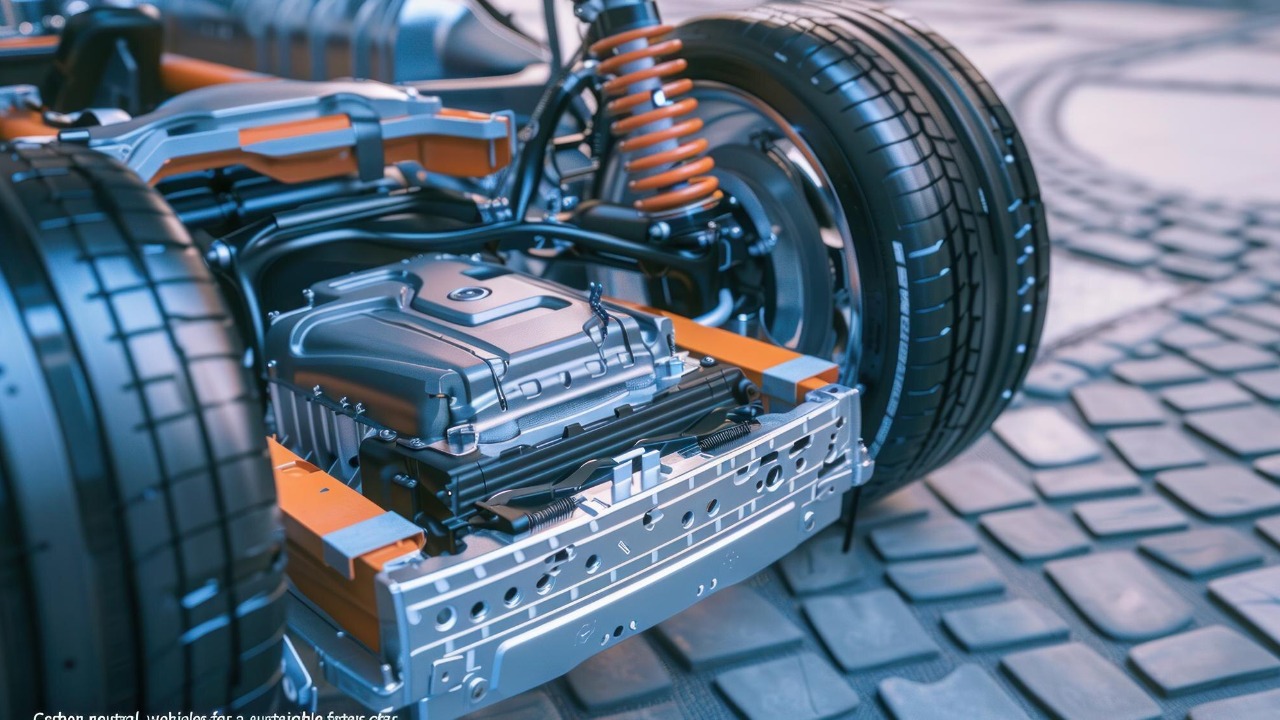

What makes this latest step different is how tightly the motor is integrated into a complete wheel-end system. Instead of treating the motor as a standalone component, YASA has packaged the stator, rotor, reduction gearing, and wheel hub into a single assembly that bolts up where a conventional hub would sit. Reporting on the new in-wheel powertrain describes a compact, record-setting axial flux motor that enables a Record-breaking compact electric motor with power density figures up to 70 kilowatts per kilogram, which is far beyond what most current EV drivetrains can manage. That density is what makes 1,000 hp per wheel plausible without turning the suspension into a boat anchor.

The prototype in-wheel powertrain that hits 1,000 hp per wheel

The headline number is simple enough to grasp: the prototype in-wheel powertrain delivers 1,000 hp at a single wheel, which means a four-motor car could, in theory, deploy 4,000 hp. That figure is not just a marketing flourish, it reflects the combined output of the axial flux motor and its integrated reduction gearing, which multiplies torque at the wheel while keeping the electric machine itself compact. The result is an unofficial power-density record for a road-car-scale motor, achieved without resorting to exotic cooling schemes or experimental materials that would be hard to industrialize.

Crucially, this is not a loose lab experiment. The unit is described as a prototype in-wheel powertrain, built to be installed on a test vehicle and evaluated under real-world conditions rather than just on a bench. Oxfordshire-based Oxfordshire engineers at YASA have focused on keeping the net weight impact low enough that the system can be considered “mass-neutral,” meaning that the extra hardware at the wheel is offset by the removal of central motors, driveshafts, and differentials. That balance is what turns a wild power figure into something that could realistically underpin a future performance EV.

From lab to road: YASA’s record-setting density and what it means

Power density is the quiet metric that decides whether a breakthrough motor ever leaves the lab. In this case, the compact axial flux unit at the heart of the in-wheel system is credited with specific outputs up to 70 kilowatts per kilogram, a level that allows engineers to chase four-figure horsepower without ballooning vehicle mass. The Thanks to YASA report on this technology notes that this axial flux approach effectively doubles the current industry standard for power density in many EV applications, which explains why the company can talk about 1,000 bhp at a single wheel without resorting to a massive, heavy casing.

That density is not just a bragging right, it is a design enabler. With such a high kilowatt-per-kilogram figure, carmakers can consider layouts that were previously off the table, such as four independent in-wheel motors on a luxury sedan or a high-riding SUV without pushing curb weight into absurd territory. A detailed technical breakdown of the Record motor highlights how the compact form factor and high specific output allow the in-wheel assembly to remain mass-neutral, so the vehicle does not gain net weight even as it adds a motor at each corner. That is a critical threshold for both performance and efficiency, because every extra kilogram must be accelerated, braked, and carried by the suspension.

Mercedes’ role and the evolution from 28-pound motors to in-wheel monsters

YASA’s leap into in-wheel powertrains did not come out of nowhere. The company is part of Mercedes, and earlier work on ultra-light, high-output motors laid the groundwork for the current prototype. A previous milestone came when a Mercedes Owned EV Motor Company YASA Beats Itself, Reveals 28 Pound Unit Making Over 1000 HP, showing that the team could already deliver four-figure horsepower from a package light enough to be lifted with one hand. That 28-pound unit was not an in-wheel design, but it proved that YASA’s axial flux architecture could hit extreme power levels without the mass penalty that usually comes with such outputs.

From there, the logical next step was to push the motor closer to the road. The new in-wheel system essentially takes the philosophy of that 28 Pound Unit Making Over 1000 HP and relocates it to the hub, then adds gearing and integration so it can directly drive the wheel. In doing so, YASA and Mercedes are testing how far they can simplify the rest of the drivetrain, potentially eliminating rear driveshafts and even some brake hardware in future vehicles. The corporate backing matters here, because only a manufacturer with Mercedes-scale resources can afford to take a radical concept like this from a lab curiosity to a fully engineered prototype ready for vehicle-level testing.

Why in-wheel motors could let carmakers ditch rear brakes and driveline hardware

Once each wheel has its own powerful motor, the rest of the hardware starts to look redundant. Reporting on the new system notes that the in-wheel powertrain’s exceptional regenerative capability could allow carmakers to remove significant rear brake componentry and even rear driveshafts, trimming cost and weight. One analysis of the technology explains that Dec engineers see a path where the rear axle of a performance EV might rely almost entirely on motor braking, with friction brakes serving mainly as a backup or for the front wheels. That is a profound shift from today’s layouts, where large rear brake discs and calipers are still required to handle repeated high-speed stops.

Removing rear driveshafts is an equally big deal. Traditional all-wheel-drive EVs use a central motor and a mechanical link to the rear axle, which adds rotating mass and packaging complexity. With a powerful in-wheel motor at each rear corner, that hardware can disappear, freeing up underbody space for batteries or cabin room. The same report on the record-breaking motor notes that the in-wheel system has been developed from the ground up to support such a simplified architecture, with the goal of delivering both cost reduction and efficiency gains. If that vision holds, future electric sedans and SUVs could have cleaner underbodies, fewer moving parts, and more interior volume, all while gaining sharper control over how torque is delivered to each wheel.

Handling, torque vectoring, and the promise of four independent 1,000 hp corners

Putting a motor in each wheel is not just about raw power, it is about control. With four independent machines, software can meter torque at each corner in real time, creating torque vectoring effects that are impossible with a single central motor and mechanical differentials. The new in-wheel system’s ability to deliver 1,000 hp per wheel means that even if a production car never uses the full figure, it has enormous headroom for fine-grained control, from stabilizing the car mid-corner to tightening its line under power. The YASA axial flux report emphasizes that this alternative to conventional radial motors is not just about efficiency, it is about enabling new vehicle dynamics strategies that treat each wheel as a fully controllable actuator.

There is also a packaging benefit for handling. By moving the mass of the motor out to the wheels but keeping it low and compact, engineers can lower the center of gravity and free up space in the chassis for suspension optimization. The record-setting in-wheel prototype is described as mass-neutral, which means that while it does add unsprung weight at the wheel, it removes equivalent or greater mass from the body, where it would otherwise raise the center of gravity. That trade-off will be a key question for chassis engineers, but the combination of high power density and software-driven torque vectoring gives them powerful tools to tune ride and handling. In practice, a future sports EV using this system could feel more agile and responsive than today’s heavy, centrally motored performance cars, even if it carries similar battery capacity.

How this Brit-built in-wheel concept fits into a wider EV motor arms race

YASA is not the only player chasing extreme in-wheel performance, and that context matters. A separate project described as This Brit built in-wheel electric motor makes over 1,000bhp despite weighing just 12.7kg, showing that British engineering teams are converging on similar targets from different angles. That unit, like YASA’s, is focused on combining high output with very low mass, and its makers argue that it could bring major gains in weight reduction, performance, and efficiency. The fact that multiple British-led projects are hitting four-figure horsepower in such small packages suggests that the underlying materials, cooling, and control electronics have reached a tipping point.

Another report on the same Brit-built concept notes that Here is a story that will make even hardened petrolheads sit up, because it shows that electric hardware can now match or exceed the power-to-weight ratios of high-end combustion engines. When I set that alongside YASA’s 28-pound 1,000 hp motor and the new 1,000 hp per wheel prototype, a pattern emerges: the EV motor arms race is no longer about simply matching combustion engines, it is about surpassing them so decisively that the debate shifts from “can it be done” to “how do we use this responsibly.” For carmakers, that means thinking carefully about traction limits, tire technology, and electronic safeguards, because the hardware is rapidly outpacing what road surfaces and drivers can realistically handle.

Efficiency, range, and the mass-neutral promise of in-wheel power

High power figures grab attention, but efficiency is what will decide whether in-wheel motors become mainstream. The new prototype is pitched as a way to improve both performance and long-duration driving, not just as a drag-strip party trick. By eliminating central driveline components and placing the motor directly at the wheel, the system cuts mechanical losses that would otherwise occur in shafts, differentials, and gearboxes. The New EV motor coverage highlights that this architecture could reduce energy losses and improve overall efficiency, which in turn supports longer range from the same battery pack.

The mass-neutral design is equally important for range. If the in-wheel system simply added weight, any efficiency gains from reduced mechanical losses would be offset by the extra mass that needs to be moved. Instead, the record-breaking compact motor and its integrated wheel-end assembly are designed so that the removal of central motors and driveline hardware balances out the added weight at each corner. The YASA prototype description explicitly notes that the goal is to add no net weight to the vehicle, which is a crucial constraint for any EV that aims to compete on range. If that target is met in production, drivers could see cars that are both quicker and more efficient, a combination that has historically been hard to achieve.

What comes next: from prototype to production and the questions still open

For all the impressive numbers, this technology is still at the prototype stage, and several big questions remain before it can reach mass production. Durability is one of them. In-wheel motors live in a harsh environment, exposed to road debris, water, and constant shock loads from potholes and curbs. YASA’s experience with compact axial flux units, including the earlier Yasa motor that weighs less than 30 pounds, gives it a head start in designing robust housings and cooling systems, but long-term testing on real roads will be the ultimate judge. Carmakers will also want to understand how the added unsprung mass affects ride comfort and tire wear, even if the overall vehicle mass stays flat.

Cost and manufacturability are the other big hurdles. Integrating a high-density axial flux motor, reduction gearing, and wheel hub into a single assembly is a complex engineering task, and doing it at scale requires new production lines and supply chains. However, the potential savings from removing rear driveshafts, differentials, and some brake hardware could offset part of that investment, especially in high-volume platforms. As I look across the reporting on this record-setting in-wheel system, from the Dec coverage of YASA’s axial flux breakthrough to the detailed breakdown of the 1,000 hp per wheel prototype, the direction of travel is clear. The EV motor is shrinking, getting lighter, and moving closer to the road, and the companies that master this shift will have a powerful advantage in the next generation of electric performance cars.

More from MorningOverview