Earth’s magnetic field was rattled by a solar outburst that arrived with almost no warning, lighting up skies and briefly reminding power grid operators and satellite controllers how vulnerable modern systems can be. The blast was not especially catastrophic, but it was unsettling for a different reason: the eruption that triggered it was so subtle at the Sun that standard forecasting tools barely registered it. As researchers dig through the data, the surprise has become a case study in how even a heavily monitored star can still catch us off guard.

What hit the planet was not a cinematic fireball but a complex disturbance in the solar wind that slipped through the usual early warning nets. It appears to have been tied to a “stealth” coronal mass ejection, a slow and faint restructuring of the Sun’s outer atmosphere that left only the faintest fingerprints in coronagraph images. The episode has sharpened a long running debate inside the space weather community: are we bumping up against the limits of current technology, or are we still looking for the wrong clues in the wrong place?

What actually hit Earth

From Earth’s perspective, the event arrived as a geomagnetic storm, a period when the solar wind suddenly becomes denser, faster, and more magnetically tangled as it slams into the planet’s magnetic field. In this case, the solar wind was dominated by a negative polarity coronal hole high speed stream, a jet of charged particles flowing out of an open patch in the Sun’s magnetic field, with what researchers described as a possible “embedded transient” riding inside it. That embedded structure, which disturbed the otherwise steady stream, is what many scientists now suspect was the signature of a stealth coronal mass ejection that had left the Sun with almost no fanfare before it reached Earth and disrupted the solar wind.

Unlike the dramatic blasts that follow obvious solar flares, this disturbance did not announce itself with a bright flash or a towering loop of plasma arcing off the solar limb. Instead, it crept outward as a subtle reconfiguration of the corona, the Sun’s outer atmosphere, that only revealed its true scale when it arrived at Earth and triggered auroras far from their usual haunts. Observers reported that the storm’s structure and timing did not match the forecasts that had been based on more visible solar activity, a mismatch that pointed directly to a hidden eruption embedded in the high speed stream described in detailed analyses of the negative polarity stream.

Why “stealth” CMEs are so hard to see

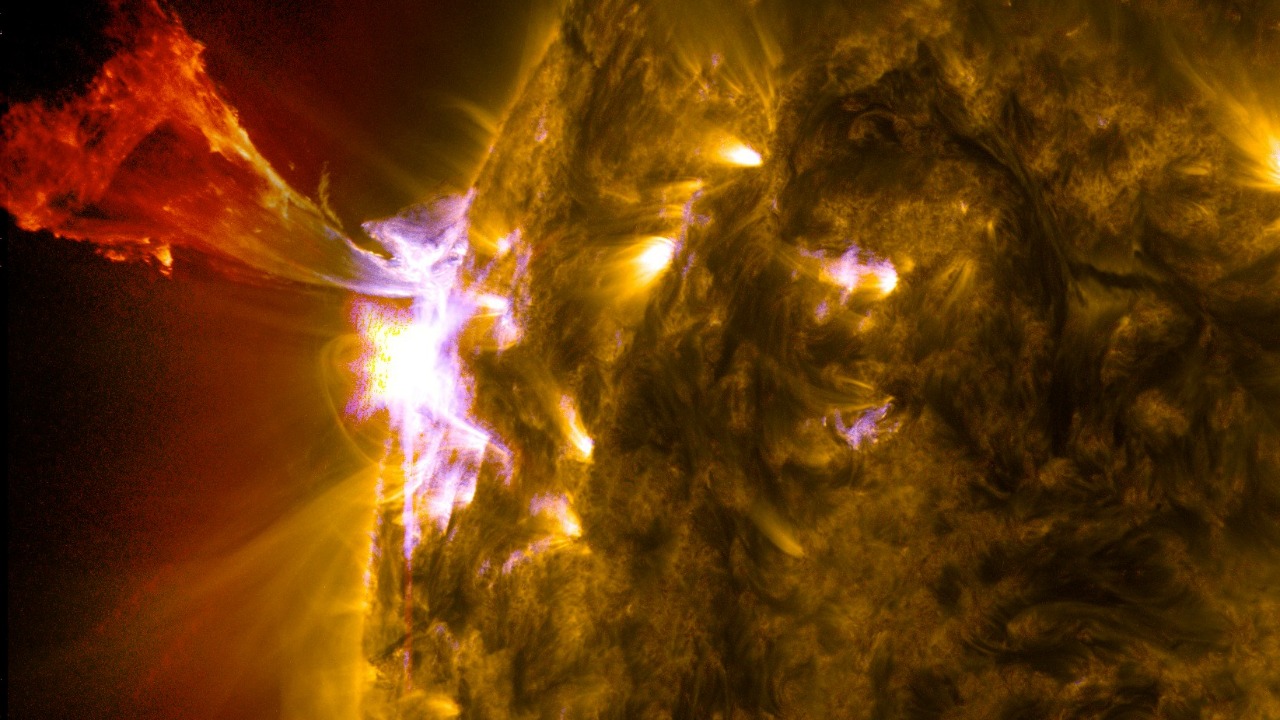

To understand why this eruption slipped past forecasters, it helps to look at how a typical coronal mass ejection behaves. A regular CME is usually tied to a visible solar flare or a filament eruption, a dramatic lifting and snapping of magnetic loops that shows up clearly in extreme ultraviolet images and coronagraph movies. Those events carve out bright, expanding halos of plasma that instruments can track as they race away from the Sun, giving forecasters a sense of their speed, direction, and potential impact. Stealth CMEs, by contrast, tend to emerge from more gradual structural shifts in the corona, with little or no accompanying flare, so the usual visual cues that trigger alerts are muted or missing.

Researchers who have gone back through data from several stealth CMEs have found that they often begin as slow, large scale reorganizations of coronal magnetic fields rather than explosive releases. After analyzing several of these events, one team concluded that the key signatures were subtle disturbances in the corona that only become obvious when viewed in hindsight across multiple wavelengths and vantage points. In the case of the recent surprise, the eruption appears to have been linked to just such a structural shift, a disturbance in the corona that did not produce the kind of bright flare that would have set off alarms but still lofted enough plasma to qualify as a CME, a pattern that matches the behavior described in studies of several stealth CMEs.

Flares, CMEs and why the distinction matters

Part of the public confusion around this storm stems from the way “solar flare” is used as shorthand for almost any solar outburst. In reality, flares and CMEs are related but distinct phenomena, and the difference matters for forecasting. A flare is essentially a flash of electromagnetic radiation, a burst of light and X rays that reaches Earth in about eight minutes and can disrupt radio communications on the sunlit side of the planet. A CME is more like a cannon shot of magnetized plasma that takes many hours to days to arrive, and it is this slower, massive cloud that usually drives the strongest geomagnetic storms and poses the greatest risk to satellites and power grids.

Space weather specialists often describe the relationship by saying that if a flare is the muzzle flash of a solar gun, the CME is the actual cannonball that slams into Earth’s magnetic shield. Key to space weather forecasting is the distinction between these two, because a bright flare without a CME may cause brief radio issues but little else, while a relatively modest flare that hides a large CME can set off a major geomagnetic storm. The recent surprise event underscored how dangerous it can be when the “cannonball” is effectively invisible at launch, a scenario that fits the warning that the key distinction between flares and CMEs is central to protecting the planet’s power grids.

How the storm lit up the night sky

For people on the ground, the most obvious sign that something unusual had happened on the Sun was not a data plot but the sky itself. As the stealth driven disturbance swept past Earth, it compressed the magnetosphere and funneled charged particles into the upper atmosphere, where they collided with oxygen and nitrogen atoms to produce shimmering curtains of green and red light. The auroras pushed far beyond their usual polar zones, reaching latitudes where residents rarely see them and prompting a rush of late night alerts and social media posts as people scrambled outside with smartphones and tripods.

In the United Kingdom, forecasters issued a rare red alert for auroral activity as the storm unfolded, warning that the Northern Lights could be visible much farther south than normal. Observers reported that the displays were more intense and more widespread than typical, with some noting unusual colors and structures in the sky. The event was widely referred to as a “stealth” storm because the underlying eruption had been so hard to spot in advance, a label that echoed descriptions of a similar episode where a coronal mass ejection, illustration was paired with the line that Scientists Didn’t See This Solar Flare Coming MARK GARLICK, SCIENCE, PHOTO as auroras appeared in more places in the sky than usual.

Why forecasting geomagnetic storms is still so difficult

From a distance, it can be tempting to assume that with fleets of satellites and decades of solar data, predicting space weather should be a solved problem. The reality is far messier. Space weather prediction is a central focus of solar terrestrial physics, but the Sun Earth system is a complex, coupled environment where small uncertainties at the source can balloon into large errors by the time a disturbance reaches Earth. The challenge lies in estimating not just whether a CME has been launched, but its speed, direction, internal magnetic structure, and how it will interact with the background solar wind and Earth’s own magnetic field along the way.

Even when a CME is obvious in coronagraph images, translating that observation into a precise forecast of geomagnetic storm intensity remains a major scientific and operational hurdle. Models must account for how the ejection expands, rotates, and deforms as it travels, and how it might merge with or be deflected by other solar wind structures. A recent review of the importance and challenges of geomagnetic storm forecasting emphasized that these uncertainties are not just academic, because they directly affect the ability of grid operators, satellite controllers, and aviation planners to prepare for potential impacts. The authors noted that the challenge lies in estimating the geoeffectiveness of a given solar event, a problem that remains stubbornly difficult despite advances in modeling and data assimilation, as highlighted in work on the importance and challenges of geomagnetic storm forecasting.

What this reveals about our blind spots on the Sun

The stealth nature of the recent eruption has forced forecasters to confront a sobering possibility: even with continuous monitoring, there may be entire classes of solar events that current systems are poorly equipped to detect. Many operational forecasts rely heavily on visible flares, sunspot counts, and coronagraph halos as proxies for risk, which works reasonably well for large, explosive CMEs. Slow, faint eruptions that emerge from the quiet corona, however, can slip through these filters, especially when they are aligned in such a way that their signatures are masked by other structures or by the viewing geometry of instruments near Earth.

Some researchers have argued that the solution lies in shifting more attention to the subtle, large scale evolution of the corona rather than just the most dramatic flares. That means mining multi wavelength data for signs of gradual magnetic reconfiguration, tracking faint wave fronts, and using stereoscopic views from spacecraft at different longitudes to catch eruptions that are nearly invisible from Earth’s line of sight. The stealth storm that just rattled Earth’s magnetic field fits the pattern of events that emerge from these quiet but significant structural changes, the kind of disturbance in the corona that was identified as the common thread in several stealth CMEs when investigators went back and reconstructed their origins using the detailed analysis of After analyzing several stealth CMEs.

The Sun’s changing mood and the risk of extreme storms

The timing of the surprise storm has added another layer of concern, because it arrived as the Sun is moving into the declining phase of its 11 year cycle. Historically, some of the most powerful geomagnetic storms have struck not at the peak of solar activity but on the way down, when the magnetic field is reorganizing and coronal holes become more prominent. That pattern raises the possibility that more high speed streams and embedded transients could buffet Earth in the coming years, even as sunspot numbers start to fall, creating a kind of “long tail” of risk that extends beyond the official solar maximum.

Space weather historians often point to past episodes when extreme storms appeared to strike out of the blue, catching societies with far less technology by surprise but still leaving marks in telegraph systems and ice core records. Modern forecasters have more tools, but they are still grappling with the same fundamental problem: the Sun can unleash complex eruptions that defy simple pattern recognition. Analyses of whether Earth is prepared for extreme solar storms have stressed that despite decades of progress, there are still significant gaps in our ability to anticipate the most severe events and predict their impact on Earth, a warning underscored by discussions of how extreme solar storms can strike out of the blue.

Why this storm matters for power grids and satellites

Even though the latest surprise did not trigger widespread blackouts or satellite failures, it served as a live fire drill for the systems that keep modern infrastructure running. When a geomagnetic storm hits, it can induce currents in long conductors such as high voltage transmission lines, pipelines, and undersea cables, potentially damaging transformers or forcing operators to take protective actions. Satellites can experience charging on their surfaces and in their electronics, increased drag in low Earth orbit, and disruptions to onboard sensors and communications links, all of which can degrade services that people rely on every day, from GPS navigation in a Tesla Model 3 to timing signals that underpin financial transactions.

The fact that this disturbance arrived with little warning meant that grid operators and satellite controllers had less time than usual to adjust configurations, reschedule sensitive operations, or put spacecraft into safer modes. It also highlighted how much those decisions depend on accurate forecasts of CME arrival times and intensities, not just on real time measurements from upstream satellites that only provide tens of minutes of lead time. The episode reinforced the argument that distinguishing between flares and CMEs, and especially recognizing when a seemingly modest flare hides a significant ejection, is essential to protecting critical infrastructure, a point that aligns with the emphasis that key to space weather forecasting is understanding which solar events can truly threaten the planet’s power grids.

How scientists hope to avoid the next surprise

In the wake of the stealth storm, researchers are treating the event as both a warning and an opportunity. By dissecting the eruption from multiple angles, they hope to identify new precursors that can be folded into operational models, such as faint coronal dimmings, slow wave fronts, or characteristic patterns in the Sun’s magnetic field evolution. Machine learning tools are being trained to sift through vast archives of solar images to flag subtle changes that human forecasters might miss in real time, while new missions are being designed to provide continuous coverage from vantage points away from the Sun Earth line, improving the odds of catching eruptions that are nearly invisible from a single viewpoint.

At the same time, there is a growing recognition that forecasting will never be perfect, and that resilience must be built into the systems that depend on space weather alerts. That means hardening satellites against charging, designing transformers that can better tolerate geomagnetically induced currents, and developing playbooks that allow operators to respond quickly even when the warning window is short. The stealth storm that just brushed past Earth’s magnetic shield was a reminder that the Sun does not owe us clear signals or convenient timing, and that the real measure of preparedness is not whether we can predict every outburst, but whether our technology and policies can absorb the surprises that slip through the cracks, a lesson that echoes the broader concern that a stealth CME can quietly form and still deliver a significant jolt to Earth.

More from MorningOverview