Memory failures often feel like personal lapses, but new research suggests the problem may be rooted in hidden architecture inside the brain’s core learning hub. Scientists have uncovered previously unknown layers in a key hippocampal region, revealing a far more intricate structure than textbooks describe and offering a fresh way to understand why some memories stick while others slip away. The discovery hints that vulnerability to disorders such as dementia, epilepsy, and ischemic injury may be wired into this layered design, long before symptoms surface.

The brain’s memory hub was never as simple as it looked

For decades, the hippocampus has been portrayed as a relatively tidy circuit, with information flowing through a few well-defined subregions that handle learning, spatial navigation, and recall. In that picture, the CA1 area, which helps consolidate experiences into long-term memory, has often been treated as a single, uniform strip of cells that behaves the same from one end to the other. That tidy model has always been a bit at odds with the messy reality of memory loss, where some abilities erode while others remain intact, but the underlying anatomical explanation has been hard to pin down.

Earlier work already hinted that this neat view was incomplete, showing that the CA1 region sits high in the entorhinal–hippocampal hierarchy and is not just a simple relay station. At the transcriptional, morphological, and functional levels, researchers have reported that CA1 is more diverse than a single slab of tissue, even though it has been traditionally viewed as one layered structure. The new work on hidden layers builds directly on that tension, replacing the old flat map with a more topographically rich blueprint that finally starts to match the complexity of real-world memory problems.

A hidden four-layer structure comes into focus

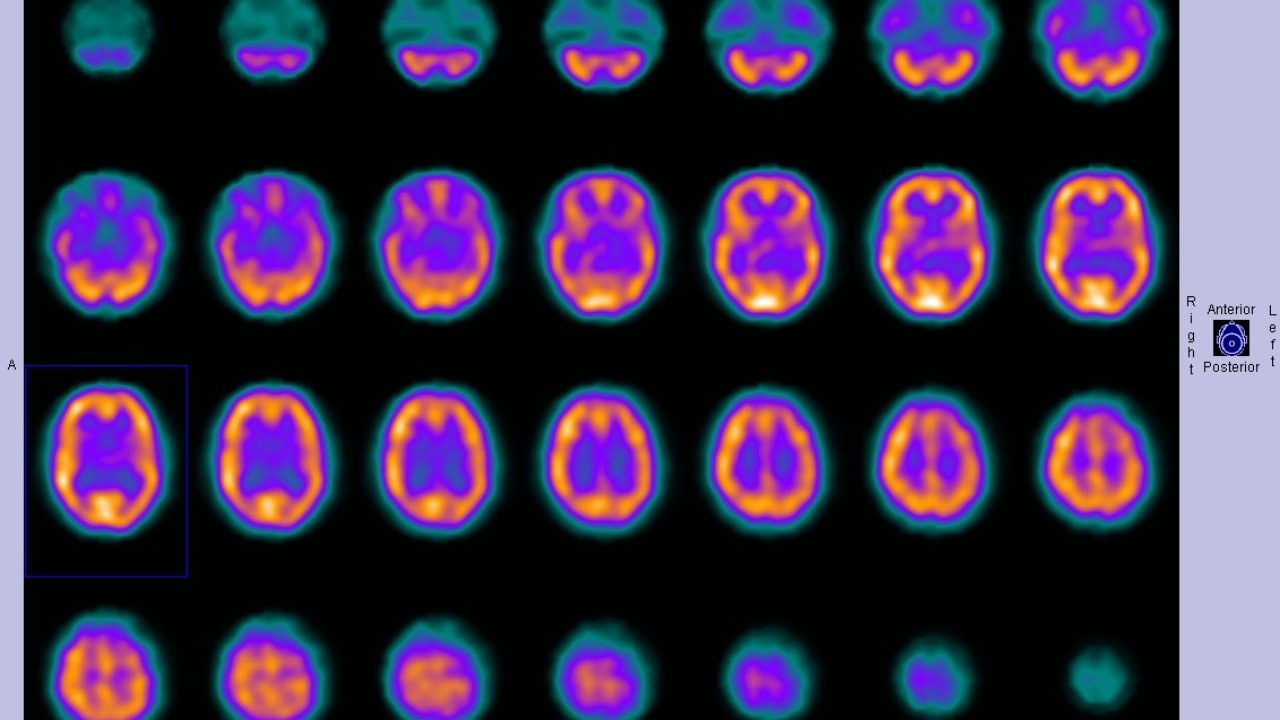

The latest studies go beyond broad hints of diversity and describe a specific, previously unrecognized four-layer organization inside the hippocampal CA1 region. Instead of a single band of pyramidal neurons, scientists now see a stack of distinct cellular strata, each with its own gene expression profile and likely its own role in processing experience. This layered pattern was not obvious under a standard microscope, which is why it escaped notice for so long, but it emerges clearly when researchers combine high-resolution imaging with molecular tools that label different cell types.

By visualizing gene RNA across CA1, the team could separate neurons into four discrete groups that line up in space, revealing a hidden architecture that reshapes how learning and recall are understood in this part of the brain. The work shows that what once looked like a single homogeneous subregion is in fact a finely partitioned structure, and that each layer may be differently affected by disease. The finding, described as a hidden four-layer structure in the brain’s key memory hub, gives researchers a new anatomical framework for asking why some memories are more fragile than others.

“Lifting a veil” on the hippocampus’s internal architecture

One of the striking aspects of this work is how it changes the way scientists talk about the hippocampus. Instead of a familiar, almost textbook diagram, they now describe the CA1 region as if a curtain has been pulled back on a previously unseen stage. The discovery of multiple cellular strata, each with its own molecular identity, turns a flat schematic into something closer to a layered city, where neighborhoods have distinct functions and vulnerabilities. That shift in metaphor matters, because it encourages researchers to look for layer-specific circuits and failure points rather than treating CA1 as a single block.

In explaining the significance, one of the study’s leaders compared the new view to lifting a veil on the brain’s internal architecture, arguing that these hidden layers may explain differences in how hippocampal circuits behave and why some are most vulnerable in certain disorders. The work, detailed in a description of hidden cellular layers in the brain’s memory center, reframes long-standing questions about memory loss as questions about which layers fail first, how they are wired, and what that means for behavior.

From cellular layers to failing memories

Once the layered structure is on the table, the next challenge is to connect it to the everyday experience of forgetting names, misplacing keys, or losing entire chapters of personal history to disease. The new research suggests that memory failures may not be random glitches but the visible outcome of damage concentrated in specific CA1 layers that handle particular aspects of encoding or retrieval. If one layer is tuned to contextual details, for example, and another to the emotional tone of an event, then selective injury could explain why some patients remember facts without feelings or places without timelines.

Researchers are already mapping which layers are most at risk in different conditions, using gene expression patterns to identify cell types that are especially fragile. When they visualized gene RNA across the CA1 region, they could see which neurons are likely to be at risk in each disorder, linking molecular signatures to clinical vulnerability. That work, described in detail in an analysis of which neurons are at risk, supports the idea that memory loss in dementia, epilepsy, or ischemic injury may track along these hidden layers rather than wiping out CA1 uniformly.

Why some hippocampal regions are hit harder than others

Clinical observations have long shown that not all parts of the hippocampus suffer equally when disease strikes. In conditions such as hippocampal sclerosis linked to dementia, epilepsy, or ischemic injury, some subfields degenerate early and severely while others remain relatively spared. That pattern has been puzzling, because CA1 has often been treated as a single unit, yet patients and autopsy studies point to pockets of extreme vulnerability within it. The new layered model offers a way to reconcile those observations with anatomy.

Detailed pathological work has already documented that the CA1-prox region can be more vulnerable than CA1-dist, a finding that surprised researchers precisely because CA1 was traditionally considered a single homogeneous subregion of the hippocampus. In one analysis of differential vulnerability, that contrast in damage patterns forced a rethink of how CA1 is organized. The newly described four-layer structure gives that rethink a concrete anatomical basis, suggesting that what looked like proximal versus distal differences may actually reflect distinct layers with their own susceptibility to metabolic stress, excitotoxicity, or inflammatory cascades.

New research is overturning the classic memory circuit

The discovery of hidden layers fits into a broader shift in how scientists conceptualize memory itself. The classic model imagines information flowing in a relatively linear path through the hippocampus, with each subregion performing a fixed computation on the way to long-term storage. Recent work has challenged that simplicity, arguing that the hippocampus is better understood as a dynamic network whose activity patterns depend heavily on context, behavior, and internal state. In that view, memory is less like a file being saved and more like a constantly updated simulation that the brain rebuilds on demand.

Earlier this year, researchers focusing on the hippocampus at the University of Chicago described evidence that upends the traditional view of how this region supports learning and recall in behaving animals. Their findings, presented as new research that upends traditional views about memory, emphasize that hippocampal circuits are more flexible and context dependent than once thought. Layer-specific architecture in CA1 dovetails with that perspective, suggesting that different strata may support different modes of processing, from rapid encoding during exploration to slower consolidation during rest.

How scientists uncovered the hidden layers

Peeling back the hippocampus’s internal structure required a combination of techniques that go far beyond standard histology. Researchers used high-throughput gene expression mapping to label neurons according to the RNA they produce, then overlaid those molecular fingerprints on precise anatomical coordinates. That approach turned a seemingly uniform sheet of cells into a mosaic of distinct populations, each clustering into one of four spatially ordered layers. The result is a kind of molecular topography that reveals boundaries invisible to the naked eye.

The work is part of a broader effort to build a cellular atlas of the brain’s memory center, integrating transcriptomic data with connectivity and physiology. In reports describing how a USC study reveals hidden cellular layers in the hippocampus, scientists outline how they combined gene profiling with advanced imaging to separate overlapping cell types. By aligning those data with known input and output pathways, they can start to infer how each layer participates in the flow of information, and which ones might be critical nodes where disruption leads to memory failure.

From anatomy to behavior: the next frontier

Identifying four distinct layers is only the first step; the harder task is to show how each one contributes to actual behavior. To do that, researchers will need to record activity from specific strata while animals learn, explore, and recall, then selectively perturb those layers to see what changes. The goal is to move from static maps to causal links between structure and function, so that a particular pattern of forgetting can be traced back to a particular layer or circuit. That kind of precision could eventually inform how clinicians interpret imaging scans or design interventions.

One of the scientists involved in the work has already framed this challenge clearly, noting that understanding how these layers connect to behavior is the next frontier and that the new framework can help pinpoint which circuits are disrupted in disease. In a detailed account of how a USC study uncovers hidden brain memory layers, the researcher, identified as Bienkowski, emphasizes that linking layer-specific circuits to behavior will clarify how disruption in particular strata leads to distinct memory symptoms. That agenda points toward experiments that pair fine-grained anatomy with tasks ranging from simple maze navigation to complex decision making.

Rethinking memory disorders through a layered lens

For patients and clinicians, the most immediate implication of this work is conceptual rather than technological. Instead of thinking of “hippocampal damage” as a single diagnosis, it becomes possible to imagine layer-specific disorders, where certain strata fail while others remain functional. That layered lens could help explain why two people with similar overall hippocampal volume loss show very different cognitive profiles, with one struggling mainly with spatial navigation and another with autobiographical recall. It also suggests that some therapies might work better if they target the molecular signatures of vulnerable layers rather than the region as a whole.

As researchers refine the map of which layers are most vulnerable in dementia, epilepsy, and ischemic injury, they can start to align those patterns with clinical trajectories and imaging markers. The earlier findings on CA1-prox versus CA1-dist vulnerability, combined with the new four-layer model, hint that future diagnostic criteria might distinguish between damage concentrated in specific strata and more diffuse degeneration. When I look at the emerging evidence, from the hidden brain layers now visible in CA1 to the long-standing clinical puzzles of selective hippocampal damage, the case for a layered approach to memory disorders feels increasingly hard to ignore.

More from MorningOverview