Soft robots that power themselves from their surroundings are moving from lab curiosity to strategic technology, promising machines that can swim the deepest oceans, survive the vacuum of space, and disappear into everyday clothing. Instead of rigid frames and bulky batteries, these devices rely on flexible materials and clever energy harvesting, turning ambient motion, pressure, or fluid flow into usable power. If the current wave of research holds, the next generation of explorers, sensors, and wearables may look less like metal drones and more like living tissue.

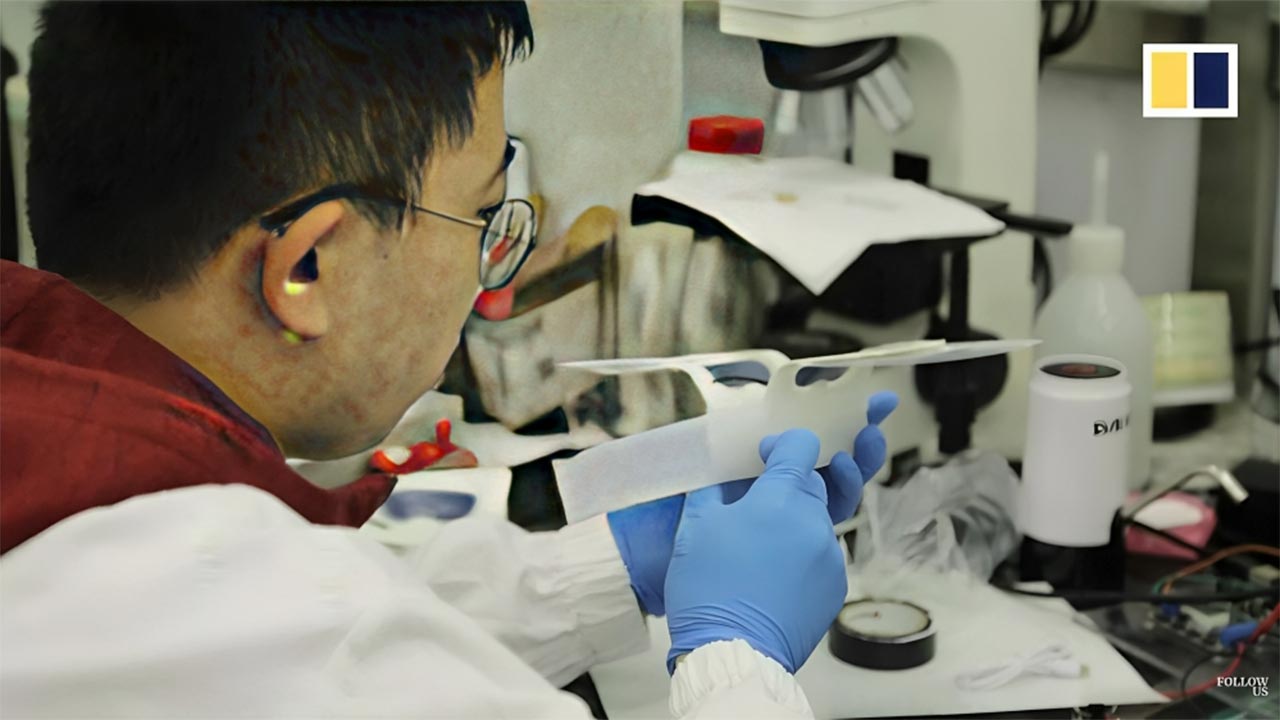

At the center of this shift is a cluster of work from China and international collaborators that treats the ocean, the human body, and even empty space as energy sources rather than hostile environments. By mimicking biological systems such as the lymph network, deep-sea snailfish, and the soft anatomy of marine invertebrates, researchers are building self-powered soft robots that can operate where conventional machines fail, from the Mariana Trench to the inside of a textile sleeve.

Why self-powered soft robots matter now

Soft robotics has been around for years, but the field has been held back by a simple constraint: power. Flexible grippers and artificial muscles are only as useful as the batteries and cables that feed them, which is why so many prototypes remain tethered to lab benches. The new generation of self-powered systems, including work highlighted under the tag Self Powered Soft Robots, attacks that bottleneck directly by harvesting energy from nothing more than ambient motion and environmental forces.

That shift matters because the most interesting places for robots to go are also the hardest to reach with wires or replaceable batteries. Deep-sea trenches, planetary surfaces, and the inside of the human body are all environments where maintenance is rare and failure can be catastrophic. By combining compliant materials with built-in power generation, researchers in China and elsewhere are positioning soft robots as long-lived, low-profile tools for exploration and monitoring, rather than fragile gadgets that need constant human support.

From the Mariana Trench to mainstream tech

One of the clearest demonstrations of this approach came when Zhejiang University researchers sent a soft machine into the Mariana Trench, the deepest known point in Earth’s oceans. Their work, described as a cover story titled “Self-powered soft robot in the Mariana Trench,” showed that a flexible device could survive crushing pressures while generating its own power, a milestone that would have been unthinkable for traditional rigid vehicles. The team’s announcement emphasized that Their Self Mariana Trench experiment was not just a stunt but a proof that soft structures can operate in one of the harshest environments on the planet.

What makes that mission so important is not only the depth record but the architecture behind it. By distributing electronics and power components within a soft body, the robot avoided the stress concentrations that crack rigid housings under extreme pressure. That same design philosophy can translate to more accessible domains, from industrial inspection in corrosive pipelines to consumer devices that need to flex and twist without breaking. The Mariana Trench project effectively turned the ocean from a threat into a partner, using the surrounding water and motion to help sustain the robot rather than destroy it.

Bioinspired designs for deep-sea exploration

The Chinese push into self-powered soft robotics is part of a broader trend that looks to marine life for engineering cues. Deep-sea snailfish, for example, thrive in conditions that would crush most submarines, thanks to bodies that distribute stress and internal structures that tolerate deformation. Building on that biology, Li and colleagues designed untethered devices described as Deep Inspired swimmers, showing that soft, distributed electronics can be used in extreme conditions without the heavy metal shells that dominate traditional ocean engineering.

These bioinspired robots are not just copies of fish, they are testbeds for a new way of thinking about machines in hostile environments. Instead of fighting pressure with thicker walls, engineers are learning to let structures deform gracefully, much like cartilage or muscle. That approach pairs naturally with self-powering strategies, since flexible bodies can integrate energy harvesters into their very fabric, turning every bend or stroke into a trickle of electricity. In deep water, where sunlight is absent and radio signals fade, that combination of soft mechanics and embedded power could be the difference between a short-lived probe and a persistent presence.

Engineering challenges in marine environments

Even with these advances, the ocean remains a brutal proving ground. Engineering in marine environments is challenging because devices must withstand high pressure, salinized fluids, and constant mechanical stress from waves and currents. A detailed review of Engineering in such conditions underscores how corrosion, biofouling, and pressure cycling can quickly degrade conventional materials and seals, especially when they are paired with rigid electronics and discrete battery packs.

Soft robots offer a partial answer by replacing sharp interfaces and rigid joints with continuous, compliant skins that distribute loads and reduce leak paths. However, they also introduce new problems, such as integrating stretchable conductors, protecting embedded sensors, and ensuring that energy harvesters remain efficient despite constant deformation. The current wave of research treats these constraints as design parameters rather than afterthoughts, using the same environmental forces that cause damage in traditional systems as sources of power and motion in soft architectures.

Soft fiber pumps and lymph-inspired wearables

While deep-sea missions grab headlines, some of the most transformative work is happening at the scale of fibers and textiles. Researchers have developed soft fiber pumps that mimic the human lymph system, using gentle peristaltic motion to move fluids through narrow channels without rigid housings or external compressors. These Soft Nov fiber pumps can be woven directly into soft robotic structures and textiles, turning clothing and flexible devices into self-contained circulatory systems.

For wearables, the implications are significant. Instead of strapping a smartwatch to the wrist or clipping a sensor to a belt, future health monitors could be built into garments that actively move cooling fluids, deliver drugs, or adjust stiffness in response to muscle fatigue. Because the pumps themselves are soft and can be powered by small, distributed energy sources, they align perfectly with the broader push toward self-powered systems. The same lymph-inspired architecture that keeps our bodies in balance could soon keep robotic exosleeves, therapeutic wraps, and adaptive sports gear running without bulky hardware.

Triboelectric nanogenerators and the rise of TENG-Bot

At the heart of many self-powered designs is a deceptively simple idea: friction can be a power source. Triboelectric nanogenerators, or TENGs, convert contact and separation between materials into electrical energy, turning everyday motion into a usable current. One flagship example is Highlights TENG Bot, a system that couples a freestanding TENG with a soft robot so that the robot’s own movement harvests the energy it needs to keep going.

What makes TENG-Bot so compelling is the closed loop it creates. Every step, bend, or twist of the soft body feeds the generator, which in turn powers actuators and control circuits, reducing or even eliminating the need for external batteries. In principle, such systems could operate indefinitely in environments with consistent mechanical stimuli, such as ocean waves, airflow around spacecraft, or the repetitive motions of human walking. For designers of wearables and field robots, that promise of near-perpetual operation from ambient motion is a powerful incentive to rethink how devices are powered and controlled.

TENG-powered robots and the ambient energy ecosystem

The TENG-Bot is not an isolated experiment but part of a broader ecosystem of triboelectric devices that treat the environment as a power grid. Under the umbrella of TENG powered robots, researchers are exploring how to embed these generators into surfaces, joints, and even clothing so that every interaction with the world becomes an opportunity to harvest energy. The same triboelectric principles that drive experimental robots can be scaled up or down, from large wave-harvesting panels to microscopic sensors that live on skin.

In practice, this means future soft robots could be designed as nodes in a distributed energy network, sharing power with each other and with surrounding infrastructure. A swarm of ocean drifters, for instance, might use wave-induced TENGs to power both locomotion and data transmission, while a field of smart textiles on a spacecraft could scavenge vibrations and crew movement. By aligning mechanical design with ambient energy flows, TENG-powered systems blur the line between structure and power plant, turning every surface into a potential generator.

China’s strategic bet on Dec Self Powered Soft Robots

China’s investment in self-powered soft robotics is not happening in a vacuum. The country has identified flexible, autonomous machines as a way to leapfrog traditional hardware-heavy approaches in sectors ranging from oceanography to personal electronics. Reporting on Dec Self Powered Soft Robots China Could Transform Deep Sea Space highlights how Chinese teams are explicitly targeting deep-sea exploration, space missions, and wearable technology as domains where soft, self-powered systems can offer both scientific and commercial advantages.

This strategy plays to China’s strengths in materials science, manufacturing, and large-scale deployment. By focusing on soft architectures that can be produced in high volumes and tailored to specific environments, Chinese researchers and companies can move quickly from lab prototypes to field-ready devices. The same technologies that enable a soft robot to survive the Mariana Trench can be adapted to inspect offshore wind farms, monitor undersea cables, or provide continuous health data through smart garments, creating a portfolio of applications that spans national security, infrastructure, and consumer markets.

From deep sea to deep space and everyday wearables

The most intriguing aspect of this research wave is how easily ideas migrate between domains. Techniques developed for deep-sea swimmers, such as distributed electronics and pressure-tolerant materials, are directly relevant to spacecraft that must endure launch vibrations and temperature swings without rigid armor. The same soft fiber pumps that mimic the lymph system in wearables can circulate coolant in compact satellites or regulate fluids in life support systems, while triboelectric harvesters that thrive on ocean waves can be tuned to capture the microvibrations of a space station hull.

For everyday users, the payoff may arrive first in the form of clothing and accessories that quietly borrow from these extreme environments. A running shirt that uses soft pumps to manage sweat, a knee brace that powers its own sensors through TENG elements, or a backpack strap that harvests walking motion to charge a phone are all logical extensions of the technologies already demonstrated in labs and testbeds. As self-powered soft robots mature, the line between exploration hardware and consumer gear will blur, with the same core principles enabling both a deep-sea probe and a health-monitoring sleeve.

What comes next for self-powered soft machines

The path ahead is not guaranteed, and several technical hurdles still stand between today’s prototypes and tomorrow’s ubiquitous soft machines. Integrating robust control systems into deformable bodies, ensuring long-term durability in corrosive or abrasive environments, and standardizing manufacturing for complex soft structures are all active areas of work. Yet the convergence of bioinspired design, triboelectric harvesting, and lymph-like fluid management suggests a coherent roadmap, one where robots are less like rigid tools and more like synthetic organisms that draw power from their surroundings.

If that roadmap holds, the impact will extend far beyond niche research projects. Self-powered soft robots could become the default choice for tasks that demand quiet operation, intimate contact with humans, or survival in places where maintenance is impossible. From the deepest trenches to orbiting platforms and the fabric of our clothes, the technologies emerging from China’s Dec Self Powered Soft Robots push and related efforts worldwide are poised to redefine what it means for a machine to be autonomous, resilient, and truly at home in its environment.

More from MorningOverview