The most powerful geomagnetic storm of the current solar cycle has just torn into the invisible bubble of charged particles that surrounds our planet, stripping away roughly three quarters of its usual density and leaving satellites and navigation systems exposed. As the storm peaked, GPS accuracy faltered across wide regions, and the protective plasma shield that normally cushions Earth’s upper atmosphere shrank to a fraction of its normal size.

What unfolded high above the clouds was not a routine space weather event but a record collapse of the plasmasphere, the doughnut-shaped region of cold, dense plasma that clings to Earth’s magnetic field. The storm’s intensity, and the scale of the erosion it caused, are forcing scientists and engineers to rethink how fragile our orbital infrastructure really is when the Sun decides to unleash its full power.

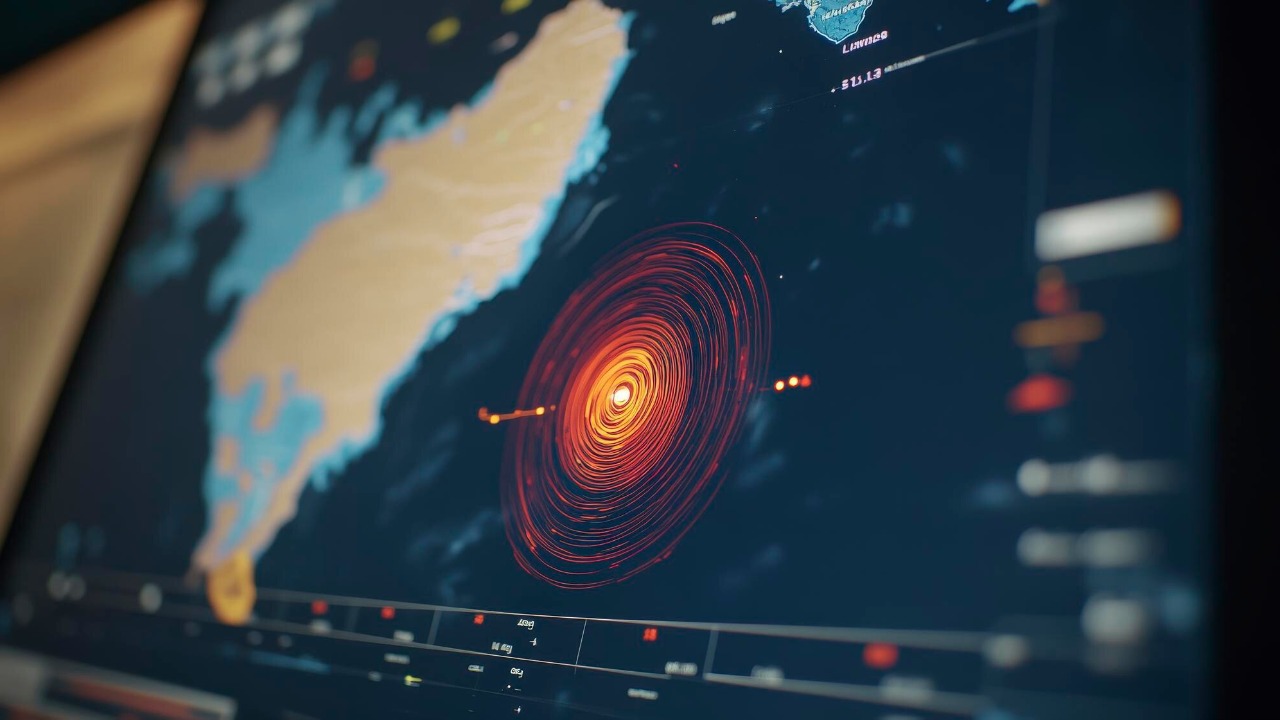

How a record geomagnetic storm crushed Earth’s plasma shield

At the heart of this story is a simple but unsettling reality: the storm did not just rattle Earth’s magnetic field, it physically squeezed the plasmasphere inward until most of it was gone. Under quiet conditions, this plasma shield extends tens of thousands of kilometers from the planet, forming a buffer of cold ions that helps regulate how energy from the solar wind penetrates near-Earth space. During the recent superstorm, that region collapsed inward to only 9,600 kilometers from Earth, a contraction so extreme that it effectively erased about 78 percent of the plasmasphere’s usual volume, a change captured in detail by Nov, Massive Geomagnetic Superstorm Crushed Earth, Plasma Shield.

That collapse was not a slow fade but a rapid implosion driven by a torrent of solar particles and magnetic fields slamming into Earth’s magnetosphere. As the geomagnetic disturbance intensified, the outer layers of the plasmasphere were peeled away and swept down the long tail of the magnetosphere, leaving only a compact core of plasma clinging close to the planet. The scale of the compression, documented as the most dramatic shrinkage ever recorded by modern instruments, marks a turning point in how researchers think about the limits of Earth’s natural defenses and how often such extreme events might recur.

The scientists who watched the shield fail in real time

What makes this storm different from past space weather episodes is not only its ferocity but the clarity with which scientists could watch the damage unfold. A research team led by Dr. Atsuki Shinbori of Nagoya University tracked the evolution of the plasmasphere in unprecedented detail, following how the cold plasma reservoir thinned, retreated, and then struggled to recover. By combining ground-based observations with satellite measurements, Dr. Shinbori’s group at the Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research (ISEE) at Nagoya University turned a violent natural experiment into a precise case study of how a superstorm dismantles the plasma shield, as described in Atsuki Shinbori of Nagoya.

For space physicists, the ability to follow that process step by step is as important as the record-setting numbers. By watching how the plasmasphere responded at different altitudes and local times, the team could separate the roles of electric fields, particle injections, and wave activity in stripping away the plasma. That level of diagnostic detail turns the storm into a benchmark for testing models that predict how future events will affect satellites, radio communications, and navigation systems, and it gives operators a clearer sense of which orbits are most at risk when the plasma shield thins to such an extreme degree.

What the Arase satellite saw as the plasmasphere vanished

The collapse of the plasmasphere was not just inferred from theory, it was directly measured by spacecraft flying through the storm. Data from the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Arase satellite showed that the region of cold, dense plasma shrank more dramatically than in any previous observation, confirming that the plasmasphere had been squeezed to a record low. As Arase crossed through near-Earth space, its instruments recorded how the usual reservoir of ions that helps refill the plasmasphere had been depleted, leaving a thinner, more tenuous environment than models had anticipated, a result highlighted in Data, Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA, Arase.

Those measurements matter because they reveal not only how far the plasmasphere can be compressed but how slowly it can bounce back. The Arase data showed that the region did not simply refill overnight once the storm subsided. Instead, the depleted zone lingered, with the cold plasma population remaining suppressed for more than four days, the longest recovery time ever documented for this part of near-Earth space, a prolonged depletion described in Nov, Not. That sluggish recovery underscores how a single extreme event can reshape the space environment for nearly a week, long after the most dramatic auroras have faded from view.

A protective bubble shrunk to one-fifth its normal size

From a global perspective, the storm’s most striking legacy is how small Earth’s protective bubble became at its peak. Scientists analyzing the event concluded that the plasmasphere, which usually envelops the planet in a thick shell of plasma, was compressed to roughly one fifth of its normal size. That contraction meant that satellites and spacecraft that typically orbit within a relatively benign plasma environment suddenly found themselves in a region where energetic particles and fluctuating electric fields were far more intense, a transformation captured in detail by Geomagnetic, Earth, Scientists.

That kind of shrinkage is not just a curiosity for space weather specialists, it has direct consequences for the technologies that modern life depends on. When the plasmasphere is compressed to one fifth of its usual extent, the boundary regions where radio waves propagate and GPS signals travel become more turbulent and less predictable. Navigation and communication systems that rely on stable ionospheric conditions suddenly have to contend with a churning, irregular medium, which can bend, delay, or scatter signals in ways that standard correction algorithms were never designed to handle.

From orbit to the open field: GPS failures on the ground

The most visible consequence of that disturbed space environment showed up not in a laboratory but in farm fields and construction sites that depend on centimeter-level positioning. As the storm disrupted the upper atmosphere, the highly precise RTK GPS, or Real-Time Kinematic Global Positioning Systems, began to fail. Specifically affected was the RTK GPS, or Real-Time Kinematic Global Positioning Systems, which farmers use to guide tractors, apply fertilizer, and plant seeds in straight, efficient rows. When the corrections that make RTK so accurate broke down, operators saw their guidance lines drift and their equipment veer off course, a disruption documented in Specifically, RTK, GPS, Real, Time Kinematic Global Positioning Systems.

Those glitches translated into real economic costs. Delayed or inaccurate field work can mean missed planting windows, wasted inputs, and lower yields, especially for large operations that rely on fleets of GPS-guided machines from brands like John Deere, Case IH, and AGCO. The storm showed that even brief interruptions in RTK corrections can ripple through supply chains, forcing rescheduling of custom applicators, grain deliveries, and labor. It also highlighted how deeply precision agriculture, surveying, and infrastructure projects now depend on a space-based system that can be knocked off balance whenever the Sun unleashes a major outburst.

Tech disruptions from a superstorm squeezed to record lows

Beyond agriculture, the storm’s impact on technology was broad and uneven, hitting systems that rely on stable satellite links and high-frequency radio paths. As the plasmasphere thinned and the ionosphere became more disturbed, GPS receivers in aviation, maritime navigation, and timing networks saw increased errors and occasional loss of lock. The superstorm squeezed Earth’s plasmasphere to a record low, disrupting tech around the world in ways that had not been documented before, with instruments registering conditions never recorded by modern sensors, a pattern described in Nov, Superstorm, Earth, Mac Oliveau, Mon.

For operators of power grids, communication networks, and satellite constellations, those anomalies were a stress test of resilience plans that often assume more moderate space weather. Increased currents in long transmission lines, fluctuating ionospheric delays on transpolar flight routes, and degraded performance in satellite internet links all underscored how a record-low plasmasphere can amplify vulnerabilities across sectors. The event is now being treated as a reference scenario for worst-case modeling, prompting renewed attention to backup navigation methods, hardened satellite designs, and more sophisticated forecasting tools that can give operators hours, not minutes, of actionable warning.

The paradigm shift in how long storms can hurt

One of the most important lessons from this superstorm is that the damage is not confined to the hours when the aurora is brightest. New measurements show that the altered space environment can persist far longer than traditional models assumed, keeping systems under stress even after the initial shock has passed. That realization has been sharpened by data from the ERACE satellite and the work of Dr shor’s team, which provided definitive proof that the way a storm lasts, not just how hard it hits, is a paradigm shift in understanding the long tail of geomagnetic disturbances, a shift highlighted in Nov, ERACE.

For planners, that means contingency timelines need to stretch from hours to days. If the plasmasphere can remain depleted for more than four days and the ionosphere stays irregular over similar spans, then backup systems, fuel reserves, and staffing plans must account for extended periods of degraded performance. It also raises questions about how multiple storms in quick succession might stack their effects, hitting a system that has not yet fully recovered from the previous blow. The emerging picture is of a space environment that can be pushed into a new, less forgiving state for nearly a week, with consequences that cascade from orbit to the ground.

Why a 78% erosion of the plasma shield raises the stakes

When scientists say that roughly 78 percent of the plasmasphere’s volume was effectively stripped away, they are not just describing a dramatic number, they are pointing to a fundamental change in how exposed Earth’s near-space environment became. With so much of the cold plasma reservoir gone, the balance between trapped radiation, incoming solar particles, and wave activity shifted in ways that can accelerate energetic particles and drive them deeper into satellite orbits. That kind of erosion increases the risk of surface charging, single-event upsets in electronics, and long-term degradation of spacecraft components that were designed for a milder background environment.

On the ground, the same erosion translates into more erratic ionospheric behavior, which is what ultimately disrupted GPS and other radio-dependent systems. The storm showed that when the plasma shield is compressed to one fifth of its normal size and its density is reduced by about three quarters, the margin for error in navigation, timing, and communication shrinks as well. For a world that leans heavily on satellite navigation for everything from ride-hailing apps to container ship routing, that is a warning that the next extreme storm could turn a space weather headline into a multi-day test of global infrastructure.

More from MorningOverview