A vast, magnetically tangled sunspot has rotated into direct view of Earth, raising the prospect of powerful solar eruptions in the coming days. The active region is large enough to dwarf our planet several times over, yet for all its drama on the solar surface, the practical question on the ground is simple: what does this mean for our technology, our skies, and our safety.

I want to unpack what scientists actually see in this giant blemish on the Sun, how it fits into a broader pattern of solar activity, and why experts say there is room for both heightened vigilance and calm perspective.

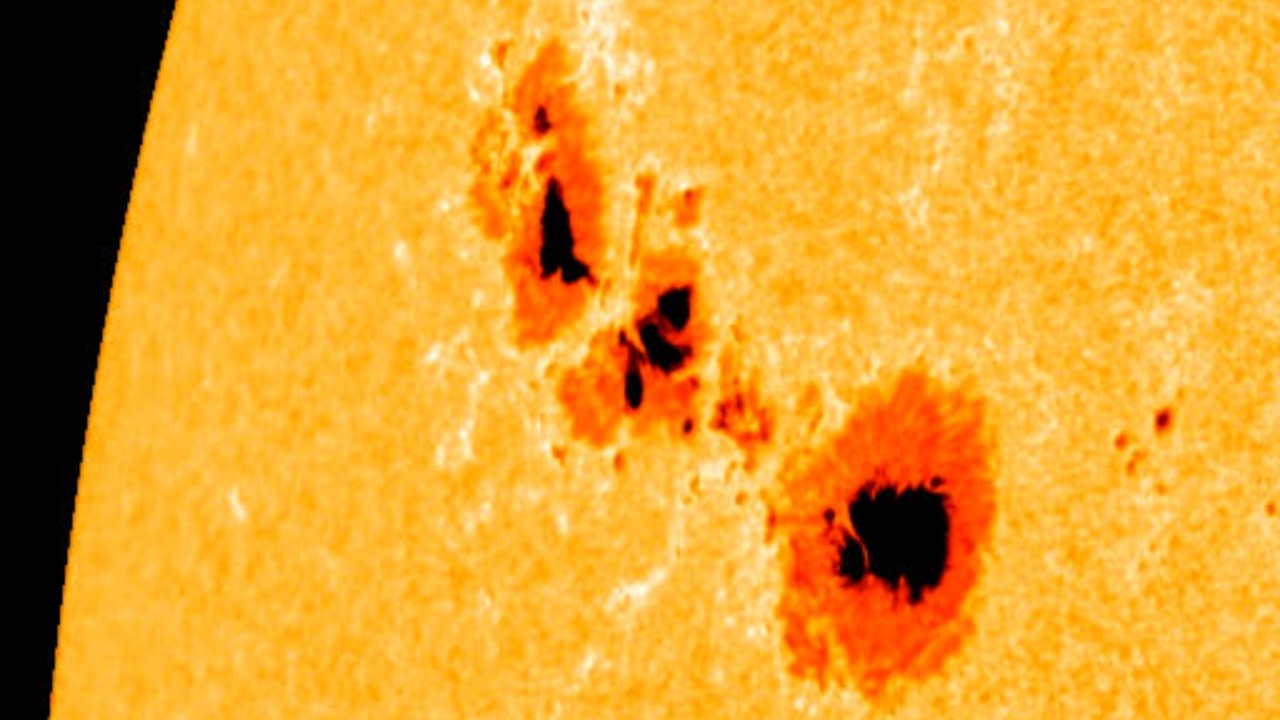

What a “huge sunspot” really is

When scientists talk about a huge sunspot, they are describing a region where the Sun’s magnetic field is so concentrated that it suppresses the normal upwelling of hot plasma, leaving a darker, cooler patch on the surface. In recent observations, one such active region has grown to more than ten times the size of Earth, a scale that turns what looks like a speck in telescope images into a structure large enough to swallow our planet many times over, as reporting on the biggest sunspot in a decade makes clear. That kind of size matters because the larger and more magnetically complex a sunspot becomes, the more energy it can store and potentially release in the form of solar flares.

Sunspots are not random stains, they are the visible footprints of the Sun’s magnetic dynamo, which twists and knots field lines as hot plasma churns in the interior. Earlier coverage of a gigantic spot on the surface of the Sun that turned to face Earth, first noticed by NASA’s Mars rover, showed how these regions can persist and reappear as the Sun rotates, sometimes growing more complex with each pass. The current Earth-facing giant fits that pattern of long-lived, evolving activity, which is why forecasters are watching it closely.

Why this one has scientists’ attention

Not every big sunspot is equally threatening, so the focus now is on the magnetic structure of this active region and its recent behavior. When a sunspot develops what researchers call a delta magnetic field, where opposite polarities are packed tightly together, it becomes a prime candidate for the most powerful eruptions, a risk highlighted when a huge sunspot pointed straight at Earth has developed a delta magnetic field. That kind of configuration can act like a coiled spring, storing energy until something triggers a sudden release.

In the days leading up to its direct alignment with our planet, this active region has already produced significant flares, including M-class events that sit in the middle of the solar flare scale and hint at the potential for stronger X-class bursts. Recent analysis of a giant sunspot larger than expected that swings to face Earth after unleashing an M-class solar flare underscores how such regions can intensify as they rotate into view, rather than fading away. That combination of size, complexity, and recent flaring is what has space weather centers on alert, even as they stress that strong activity does not automatically translate into severe impacts on the ground.

From dark patch to solar flare: how eruptions unfold

The real concern with a massive sunspot is not the dark patch itself but the explosive events it can trigger. A solar flare is essentially a sudden flash of radiation, an intense burst of energy released when twisted magnetic field lines snap and reconnect above a sunspot. NASA’s overview of solar storms and flares describes these eruptions as explosions of particles, energy, and magnetic fields that can race outward from the Sun and, in the worst cases, buffet Earth’s magnetic environment.

At a more granular level, a flare is the visible and high-energy signature of a process that starts with magnetic stress building up in the corona above a sunspot. As one technical explainer on solar flare definition notes, the explosion on the Sun’s face occurs after energy has accumulated to the point where the magnetic configuration can no longer hold, releasing radiation across the spectrum and sometimes hurling clouds of charged particles into space. When a sunspot is as large and magnetically tangled as the one now facing Earth, the stage is set for multiple such eruptions, though exactly when and how strong they will be remains uncertain.

What an X-class flare could mean for Earth

Among solar flares, X-class events sit at the top of the scale, and a giant active region like this one is capable of producing them. Analysts tracking the current sunspot have already linked it to strong activity and warned that an X-class burst could follow, a scenario echoed in coverage of a giant new sunspot and X-class solar flare that could bring bright auroras. In such a case, the first thing to reach Earth would be electromagnetic radiation, including X-rays and ultraviolet light, which can disturb the upper atmosphere within minutes.

If the flare is accompanied by a coronal mass ejection, a vast bubble of magnetized plasma, the second act arrives hours to days later when that cloud slams into Earth’s magnetic field. NASA’s description of what solar storms can do notes that the most severe of these events can disrupt power grids, satellite operations, and communications. The current sunspot’s Earth-facing position means any such eruption would have a more direct path toward our planet, which is why forecasters are watching for signs of an X-class flare even as they emphasize that not every large active region delivers a worst case.

Why experts say “no need to panic”

Despite the dramatic imagery of a dark, gaping region on the Sun, space weather specialists are careful to balance concern with reassurance. When a similarly imposing sunspot doubled in size overnight while pointing toward Earth, scientists stressed there was no need to panic, even though it had the potential to produce solar flares. The reasoning then, as now, is that Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere provide substantial protection from the most harmful radiation, and modern infrastructure is designed with at least some level of solar activity in mind.

That does not mean the risks are imaginary, only that they are managed and probabilistic rather than guaranteed catastrophe. The same reporting that highlighted the huge sunspot pointed straight at Earth has developed a delta magnetic field also underscored that even magnetically complex regions can rotate away without unleashing their full potential. I see the current situation in a similar light: a reason for heightened monitoring and practical preparation, not for alarmist predictions that outrun what the data supports.

How a storm could hit technology and daily life

Where a powerful flare and associated storm would be felt most directly is in the systems that rely on the upper atmosphere and near-Earth space. High frequency radio communications, used by aviation, maritime operators, and amateur radio enthusiasts, are particularly vulnerable when solar radiation suddenly ionizes the upper layers of the atmosphere, a point underscored in analysis of how such disturbances mainly affect HF radio communications. Airlines can reroute polar flights, ships can switch frequencies or modes, and emergency services can lean on backup channels, but those adjustments depend on timely warnings.

Satellite navigation and timing are another pressure point, especially for sectors that lean heavily on precise GPS signals. Agricultural experts like Griffin have already warned that during weeks of heightened solar storms, farmers should expect that disturbances are likely to cause GPS interference, which can throw off auto-steer tractors and variable-rate application systems. A major storm from the current sunspot could produce similar headaches for logistics fleets, rideshare drivers, and anyone whose work depends on centimeter-level positioning, even if the broader public only notices a brief glitch in their mapping apps.

Where to find real-time forecasts

With a sunspot of this size facing Earth, the most useful tool for the public is not a dramatic image but a reliable forecast. The NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center maintains a constantly updated portal where users can track current solar conditions, geomagnetic indices, and alerts, and Griffin has explicitly encouraged farmers to monitor the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center for real-time updates when storms are expected. For anyone whose work or equipment is sensitive to space weather, that site is effectively the official dashboard.

For a more granular look at the near future, forecasters publish a rolling 3-day forecast that outlines expected solar flare probabilities, geomagnetic storm levels, and potential impacts. I see that short-term window as especially important while the current sunspot is squarely facing Earth, since any major eruption in this period has a clearer line of sight to our planet. Checking those forecasts once or twice a day is a far better guide to risk than any viral image or social media rumor.

The upside: brighter auroras and a more active sky

Not all consequences of a giant sunspot are negative. When a strong flare and associated storm interact with Earth’s magnetic field, they can energize particles that stream into the upper atmosphere near the poles, lighting up the sky with vivid auroras. Analysts tracking the current active region have already suggested that an X-class flare from this sunspot could bring especially bright auroras, potentially visible much farther from the poles than usual.

For skywatchers, that means the same magnetic turbulence that worries grid operators can also deliver rare opportunities to see the northern or southern lights from places that normally sit outside the auroral oval. Technical explainers on solar storms point out that these phenomena create spectacular auroras as particles collide with oxygen and nitrogen high above Earth. If the current sunspot does unleash a strong storm, I expect social feeds to fill with shimmering curtains of green and red, a reminder that space weather is as much about beauty as it is about risk.

How this fits into the broader solar cycle

The appearance of a giant, Earth-facing sunspot is not a random fluke, it is part of the Sun’s roughly 11-year cycle of waxing and waning activity. As the cycle approaches its peak, or solar maximum, sunspots become more numerous and more intense, and the odds of large flares and storms increase accordingly. Earlier reports on a sunspot the size of Earth itself that rotated into view, after first being spotted by NASA’s Mars rover, showed how these features can reappear over multiple rotations, growing and changing as the underlying magnetic fields evolve.

In that context, the current giant sunspot is a sign that the Sun is in a more active phase, not that it has suddenly become more dangerous in some unprecedented way. Coverage of the biggest sunspot in a decade emphasized that such large regions tend to cluster around the peaks of solar cycles, which is exactly when forecasters expect more frequent storms. I see the present moment as a reminder that we are living through one of those peaks, with all the attendant need for better monitoring, infrastructure resilience, and public literacy about what space weather can and cannot do.

More from MorningOverview