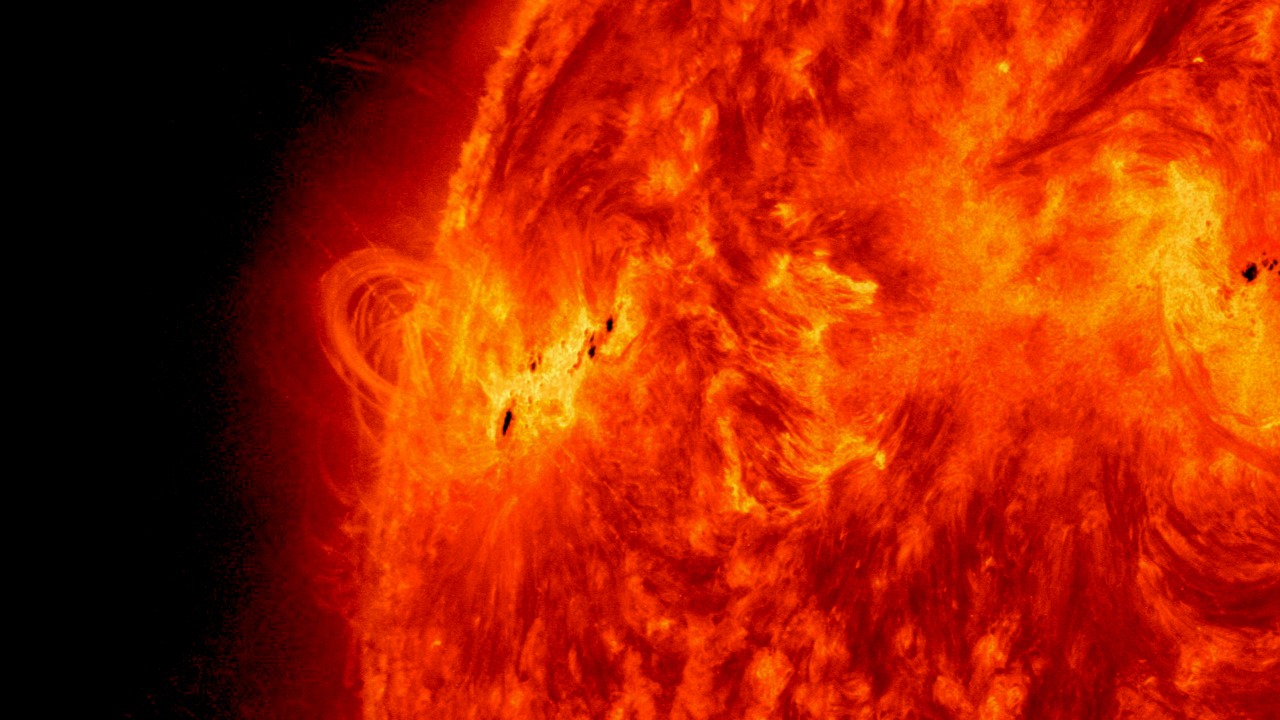

A vast, volatile blemish has opened on the face of the Sun, and it is already rewriting the current solar cycle’s record book. The decade’s largest sunspot, a complex tangle of magnetism more than ten times wider than Earth, is now pointed toward our planet and primed to unleash powerful eruptions that could light up the night sky with vivid auroras while testing the resilience of modern technology.

Solar physicists are watching this region closely because its size and structure make it a likely source of intense solar flares and related outbursts in the days ahead. As the active region rotates across the Earth-facing side of the Sun, the stakes range from spectacular northern lights at unusually low latitudes to short-lived radio blackouts and potential disturbances to satellites and power infrastructure.

Why this sunspot stands out from a restless Sun

The new active region dominating the solar disk is not just another dark patch, it is one of the most imposing sunspots of the past ten years. Observations describe a massive complex, more than ten times the diameter of Earth, with multiple dark cores stitched together by bright, magnetically charged filaments that signal intense stored energy ready to be released as flares. That scale alone puts it in rare company for the current solar cycle and explains why forecasters are treating it as a prime candidate for major eruptions.

On December 1, 2025, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory identified the region as Active Region 4294, part of a cluster sometimes labeled AR 4294-96, and early analysis flagged it as one of the biggest sunspot groups seen in a decade and a likely source of multiple solar flares in the near term. Reporting on the event notes that the structure spans an area more than ten times wider than Earth and is already producing intense bursts of electromagnetic radiation, a hallmark of a magnetically complex region that can evolve quickly into an engine for powerful space weather.

From AR 4294-96 to X-class: what forecasters expect next

Size alone does not guarantee a disruptive solar storm, but the configuration of this region suggests it is capable of producing the most energetic category of flare. Early assessments of AR 4294-96 describe a sprawling, magnetically mixed sunspot that has already fired off smaller eruptions and is now being watched for the kind of rapid reconfiguration that can trigger X-class events, the top tier on the solar flare scale. When a region this large sits squarely on the Earth-facing side of the Sun, any major outburst has a clear path toward our planet.

Coverage of the developing situation frames the region as a “Giant New Sunspot And X-Class Solar Flare Could Bring Bright Auroras” scenario, with experts warning that the same magnetic complexity that makes AR 4294-96 visually striking also makes it unstable. The designation “96” attached to the active region underscores that it is part of a broader, evolving complex, and forecasters are treating that cluster as a single, high-risk engine for strong flares that could arrive in bursts over several days rather than as a one-off event.

How this compares with earlier solar heavyweights

To understand the stakes, it helps to compare AR 4294-96 with some of the standout regions from the current solar cycle. Earlier in the cycle, a group of sunspots designated as NOAA Active Region 13664 grew rapidly and dominated the solar disk during the last week of April, providing a template for how a large, magnetically complex region can evolve from a curiosity into a major space weather driver. That cluster, chronicled in detail in “The Evolution and Impact of Active Region 13664,” showed how repeated flaring and shifting magnetic fields can reshape a region’s footprint over days while steadily feeding energy into the surrounding corona.

More recently, the Behemoth sunspot AR3664 offered a vivid demonstration of what a giant region can do when it reaches peak complexity. That active region unleashed an X3-class flare, one of the stronger events of the cycle, which sparked radio blackouts across parts of North America, South America, eastern Europe, and eastern Africa and set the stage for widespread auroras. In that case, the combination of a large, magnetically twisted sunspot and favorable alignment with Earth produced a textbook example of how a single region can dominate space weather for days, a pattern that now has forecasters drawing parallels as they track AR 4294-96.

Solar Cycle context and a possible 100-year rhythm

The emergence of such a large sunspot comes at a pivotal moment in the broader rhythm of solar activity. Researchers tracking the current Solar Cycle have noted that we may be nearing the end of its maximum phase, the period when sunspots and flares are most frequent, yet the Sun is not behaving exactly as expected. Instead of a smooth decline, the star is delivering bursts of intense activity, including giant regions like AR 4294-96, that hint at deeper cycles layered on top of the familiar 11-year pattern.

One line of research points to a mysterious, roughly 100-year solar cycle that may have just restarted, potentially ushering in decades of more dangerous space weather than the recent past. In that view, the current Solar Cycle maximum is not an isolated spike but part of a longer upswing in activity, with large, complex sunspots acting as visible markers of a more energetic Sun. If that interpretation holds, the appearance of the decade’s biggest sunspot is less an anomaly and more a preview of a period in which Earth will face more frequent and more intense solar storms.

What the official forecasters are seeing right now

While long-term patterns matter, the immediate question is what this active region is doing today and how it might affect Earth in the coming days. At the center of that effort is NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, which issues a rolling forecast discussion that dissects the latest solar imagery, magnetic field measurements, and flare statistics. In its current outlook, the center highlights the large, Earth-facing sunspot complex as a key driver of elevated flare probabilities, with particular attention to the risk of strong events that could cause radio blackouts and set up geomagnetic storms if accompanied by coronal mass ejections.

The same forecasting apparatus has recent experience tracking giant regions, including the monster sunspot AR3664 that grew to be roughly 15 times wider than Earth and demanded continuous monitoring for further activity. In that case, the forecast discussion from NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center emphasized how quickly a large region can evolve, with new magnetic knots emerging and merging over hours, and that lesson is now being applied to AR 4294-96 as analysts watch for signs that its internal structure is tightening into the kind of configuration that often precedes an X-class flare.

From flares to auroras: how energy reaches Earth

When a sunspot like AR 4294-96 unleashes a major flare, the first impact is a surge of electromagnetic radiation that races to Earth at the speed of light. These solar flares are eruptions from the Sun’s surface that can disrupt the ionosphere, the charged layer of the upper atmosphere that radio signals bounce off, leading to sudden high-frequency radio blackouts on the sunlit side of the planet. The most powerful events, classified as X-class, sit at the top of a scale that also includes weaker C-class and M-class flares, and they are the ones most likely to produce noticeable effects for aviation, maritime communications, and emergency services.

The most dramatic sky shows, however, usually depend on something slower but more massive: coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, that sometimes accompany big flares. If aimed at Earth, CMEs can trigger auroras as they interact with our magnetic field, and they may interfere with power grids and damage satellites in their path, turning a beautiful light display into a test of infrastructure resilience. In practical terms, that means a giant flare from AR 4294-96 that is coupled with a well-aimed CME could both paint the sky with bright auroras and force grid operators, satellite controllers, and airlines to activate space weather contingency plans.

Why this could be a rare aurora opportunity

For people on the ground, the most tangible consequence of a giant sunspot’s tantrum is the chance to see the northern or southern lights far from their usual haunts. When a strong geomagnetic storm hits, the auroral oval that normally hugs high latitudes can expand toward the mid-latitudes, bringing shimmering curtains of green and red light to places that rarely see them. The current configuration of AR 4294-96, combined with its Earth-facing position, raises the prospect that a major eruption could push auroras into skies over the northern United States, central Europe, or similar latitudes in the southern hemisphere.

Recent experience shows how quickly that can happen. A solar storm earlier in the current cycle impacted some regions of the U.S., producing visible auroras and prompting reminders that the website www.swpc.noaa.gov is the place to find the northern lights forecast and other space weather information. If AR 4294-96 delivers a strong flare and associated CME while it is still well aligned with Earth, aurora chasers from Montana to Michigan, or from Scotland to Germany, could find themselves with a rare window to see the lights without leaving home, provided skies are clear and local light pollution is low.

Risks for technology, from planes to power grids

The same energy that powers auroras can also stress the systems that underpin modern life. When a CME slams into Earth’s magnetic field, it can induce electric currents in long conductors such as power lines, pipelines, and undersea cables, potentially overloading transformers and control equipment. Even moderate storms can force grid operators to adjust how they run networks, while more severe events raise the risk of localized blackouts or equipment damage, especially at higher latitudes where geomagnetic effects are strongest.

Satellites and aviation are also in the crosshairs. High-energy particles associated with solar storms can degrade satellite electronics, interfere with GPS accuracy, and increase drag on spacecraft in low Earth orbit, which is a particular concern for large constellations like Starlink. For airlines, especially those flying polar routes between cities such as New York and Hong Kong or London and Tokyo, strong solar storms can disrupt high-frequency radio communications and increase radiation exposure for crew and passengers, prompting rerouting or altitude changes. The history of events like the X3-class flare from the Behemoth sunspot AR3664, which produced radio blackouts across multiple continents, is a reminder that a giant region like AR 4294-96 is not just a curiosity for astronomers but a real operational concern for industries that rely on space-based and high-frequency systems.

How to follow the storm from your backyard

For most people, the practical question is how to know when to step outside and look up, and when to be aware of potential disruptions. The most direct route is to keep an eye on official space weather updates, particularly the forecast discussion that synthesizes the latest solar observations into short-term expectations for flares and geomagnetic storms. That product, issued by NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, translates the complex physics of regions like AR 4294-96 into user-friendly alerts that indicate the likelihood of radio blackouts, satellite drag, and auroral activity over the next few days.

At the same time, amateur observers can track the evolution of the sunspot itself through publicly available imagery from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory and other instruments, which show how the dark cores and surrounding bright regions change from day to day. When a region is described as a Giant New Sunspot And potential source of an X-Class Solar Flare Could Bring Bright Auroras, it is a signal that the coming nights may offer something special, and that a quick check of local forecasts, light pollution maps, and aurora alerts could pay off in a memorable view of the sky. For those who want a deeper dive into the science, detailed explainers on solar flares versus coronal mass ejections, the evolution of past giants like Active Region 13664, and the broader Surprising behavior of the current Solar Cycle provide context for why this particular sunspot has captured so much attention.

More from MorningOverview