The world’s largest operating fusion tokamak is about to go quiet for several years, not because of failure, but because its builders want it to do far more than it managed on its first outing. After a successful first plasma campaign, the JT‑60SA machine in Japan is entering a roughly three‑year pause so engineers can strengthen its hardware, sharpen its diagnostics, and prepare it for the kind of high‑performance plasmas that will shape the next generation of fusion reactors. The hiatus is a reminder that in fusion, progress often looks like deliberate slowdown, as scientists trade short‑term spectacle for long‑term reliability.

That choice matters far beyond a single laboratory in Naka. JT‑60SA is the flagship device in a partnership between Europe and Japan, and it is designed to answer questions that will determine how quickly fusion can move from experimental halls to commercial plants. The coming upgrade period is less a retreat than a pivot, turning a record‑setting machine into a precision tool for understanding how a real fusion power station might behave.

From first plasma to planned pause

The story of JT‑60SA’s pause only makes sense in light of how quickly the machine has already moved. After years of construction, the Integrated Project Team brought the device’s integrated commissioning back online in May 2023, and, after careful checks, the team achieved the first plasma in October of that year. That initial campaign validated the core systems, from magnets to control software, and confirmed that the tokamak could confine a plasma long enough to justify more ambitious experiments, as described in the detailed account of recent progress of JT‑60SA.

Once that milestone was in hand, the operators faced a strategic choice: keep running modest plasmas to generate incremental data, or halt operations and rework the machine for the high‑power regimes that truly matter for future reactors. They chose the latter. Planning documents describe a phased approach that alternates machine and experiment periods, and the current pause fits squarely into that pattern, giving engineers room to reinforce components, refine control systems, and install new diagnostics before the next high‑heating‑power phase begins.

Why Europe and Japan built the world’s largest operating tokamak

JT‑60SA is not just another physics experiment; it is the centerpiece of a political and scientific pact between Europe and Japan to keep fusion research moving while larger, slower projects work through their own challenges. The construction of JT‑60SA is explicitly framed as a collaboration between Europe and Japan under the so‑called Broader Approach, a program meant to complement the much larger International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. By pooling industrial capacity and scientific expertise, the partners have created a machine that can explore reactor‑relevant plasmas years before a commercial plant is built.

That joint ownership also shapes the stakes of the current pause. For Europe, JT‑60SA is a proving ground for technologies and control strategies that will eventually feed into European demonstration plants. For Japan, it is a way to maintain leadership in magnetic confinement research and to host a facility that can train a new generation of fusion engineers. The shared investment means that every upgrade decision, from magnet protection to diagnostic placement, is weighed not only for its scientific payoff but also for what it teaches both partners about running a complex, multinational fusion program.

A stepping stone toward ITER and beyond

In the broader fusion landscape, JT‑60SA is often described as a bridge between today’s experiments and tomorrow’s reactors, and that is not just rhetoric. The JT‑60SA represents a significant advancement in nuclear fusion and serves explicitly as a stepping stone toward the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. Its size, magnetic configuration, and heating systems are chosen to mimic many of the conditions ITER will face, but in a more flexible, less radioactive environment where engineers can iterate quickly.

That role is especially important given the difficulties facing ITER itself. In the south of France, a collaboration among 35 countries has been building the ITER device, but new documents have highlighted serious schedule and cost problems for that project. Against that backdrop, a functioning, upgradable tokamak like JT‑60SA becomes more than a test bed; it is a hedge against delay, a place where the fusion community can continue to refine scenarios, validate models, and train operators even if ITER’s timeline stretches.

Inside the phased plan: why a three‑year break now

The decision to pause JT‑60SA for roughly three years is not an ad hoc reaction to technical trouble; it is baked into the project’s long‑term roadmap. Future operation plans describe how the JT‑60SA project adopts a phased approach in which machine and experiment periods (often labeled M and E) alternate, with each machine phase used to improve plasma performance and prepare for the next experimental push. The description of this Future plan makes clear that extended shutdowns are a feature, not a bug, of the strategy.

In practical terms, the upcoming pause is timed to bridge the gap between the relatively gentle first‑plasma campaign and a far more demanding high‑heating‑power phase. The Integrated Project Team needs time to inspect components that have now seen real plasma conditions, to reinforce systems that will face higher loads, and to integrate new diagnostics that were not ready for the initial run. By clustering these interventions into a single, well‑planned outage, the team aims to minimize unplanned downtime later, when the machine is operating closer to reactor‑relevant conditions.

New diagnostics: sharpening the view of the plasma edge

One of the most important upgrades planned during the pause is a suite of new diagnostic systems that will give physicists a much clearer view of what is happening at the edge of the plasma, where heat and particles flow toward the reactor walls. The fusion reactor JT‑60SA, built by Europe and Japan, is being equipped with advanced tools such as edge Thomson scattering to measure temperature and density profiles with high precision, as described in the report on new diagnostic systems. These instruments are essential for understanding how to protect components while still squeezing as much performance as possible from the plasma.

Better diagnostics are not just about prettier plots; they directly influence how operators run the machine. With more accurate measurements of edge conditions, control systems can respond more quickly to instabilities, heating systems can be tuned to avoid damaging power spikes, and theorists can test their models against richer data sets. The pause gives engineers the breathing room to install and calibrate these systems properly, rather than bolting them on around ongoing experiments and risking both safety and data quality.

Preparing for 2026: higher power, tougher conditions

The upgrades now underway are aimed squarely at a new experimental campaign planned around 2026, when JT‑60SA is expected to operate at much higher heating power and in more advanced confinement regimes. Since achieving first plasma in October 2023, the world’s largest operating tokamak has been undergoing modifications to prepare for these 2026 experiments, including work on magnet protection, power supplies, and systems that will help the machine reach and sustain high‑confinement (H‑mode) plasmas, as outlined in the plan for upgrading JT‑60SA. The goal is to push the device closer to the conditions a power plant would face, without crossing into the full complexity of a burning plasma.

Those ambitions come with technical risk, which is precisely why the team is willing to accept a multi‑year pause now. Running at higher power will stress the superconducting magnets, the vacuum vessel, and the heating systems in ways the first campaign did not. By reinforcing hardware and refining control algorithms in advance, the operators hope to avoid the kind of sudden failures that can sideline a fusion machine for years. The 2026 campaign is meant to be a sustained exploration of high‑performance regimes, not a brief stunt, and that requires a level of preparation that cannot be done on the fly.

What JT‑60SA is built to learn

Beyond the immediate milestones, JT‑60SA has a clear scientific mission: to explore the plasma regimes that matter most for future reactors and to do so with enough flexibility to test different operating scenarios. Thanks to its enhanced plasma confinement features and its powerful heating systems, the machine will allow the exploration of internal transport barriers, advanced current profiles, and high‑beta plasmas that approach the limits of what magnetic fields can safely confine, as laid out in the description of its main research objectives. These are not abstract goals; they map directly onto the design questions engineers face when sketching out commercial fusion plants.

In practice, that means JT‑60SA will spend much of its life probing how to shape the plasma current, how to distribute heating power, and how to manage exhaust so that walls and divertor plates survive long campaigns. The pause and upgrade period are part of that mission, because they allow the team to add the sensors and actuators needed to test more sophisticated control strategies. Each new diagnostic channel, each refined feedback loop, is another lever the operators can pull to see how a reactor‑class plasma responds, and the lessons learned will feed into both ITER and the demonstration plants planned to follow it.

How JT‑60SA compares with other fusion giants

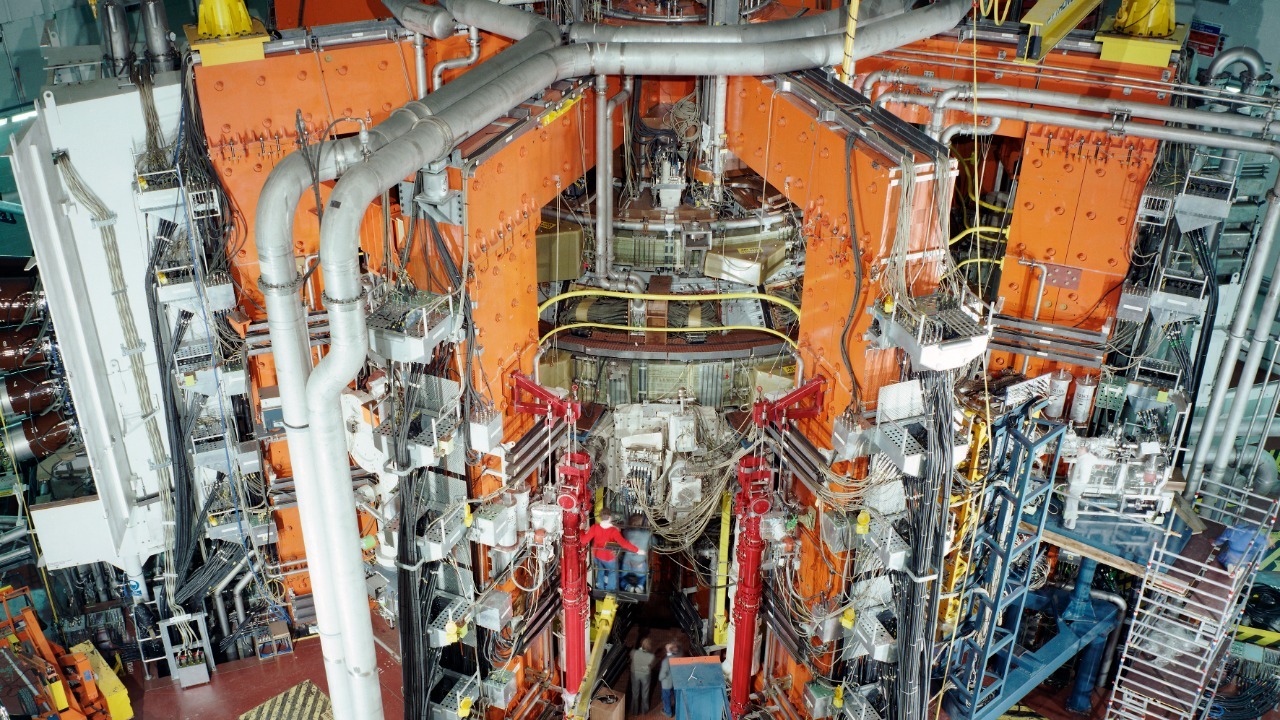

JT‑60SA’s status as the world’s largest operating tokamak is not just a matter of pride; it shapes what the machine can do and how it fits into the global fusion ecosystem. The JT‑60SA is currently a joint project by the EU and Japan, with participation by Britain, and its size and magnetic field strength put it in a different league from smaller national devices, as noted in coverage of how The JT‑60SA powers up. That scale allows it to access plasma conditions that are closer to those expected in ITER and future reactors, particularly in terms of confinement time and stability.

At the same time, JT‑60SA is deliberately less complex than ITER, which must handle nuclear heating from fusion reactions and the associated materials challenges. In that sense, the Japanese‑European machine occupies a sweet spot: large enough to be relevant, but still flexible and accessible enough to support rapid experimentation and hardware changes. The current three‑year pause is a direct expression of that flexibility, something that would be far harder to achieve once a device is fully activated by fusion neutrons and surrounded by thick biological shielding.

Why a deliberate slowdown can speed fusion up

From the outside, a three‑year shutdown of the world’s largest operating tokamak might look like a setback, especially at a time when private fusion startups are promising aggressive timelines and glossy prototypes. I see it differently. The JT‑60SA project is choosing to invest in robustness and diagnostic clarity now, rather than chasing short‑term records that would leave the machine brittle and poorly understood. That choice reflects a hard‑won lesson from decades of fusion research: the path to a working power plant runs through careful, reproducible physics, not one‑off demonstrations.

It also reflects the realities of running a multinational program. Europe and Japan have to justify their spending to governments and publics who are watching both ITER’s struggles and the rapid claims of private ventures. By structuring JT‑60SA’s life around planned pauses and upgrades, the partners can show a clear sequence of goals, investments, and payoffs. The coming three‑year hiatus is one of those investments, a bet that a better‑instrumented, more resilient machine in 2026 will do more to advance fusion than a few extra years of modest, under‑diagnosed plasmas today.

More from MorningOverview