Earth’s crust did not always behave like the rigid, jostling plates we learn about in school. New work suggests our planet once wore a softer, intermittent shell, a “squishy” surface that occasionally cracked and churned before stiffening again, and that subtle shift in behavior could reshape how I think about which distant worlds might host life. If Earth’s early, pliable skin helped bridge the gap between a molten young planet and the stable plate tectonics we know today, then similar in‑between states on other worlds may be just as important as the fully developed systems astronomers usually prize.

Instead of treating plate tectonics as a simple on‑off switch for habitability, the emerging picture is of a spectrum, with Earth’s own history revealing a crucial middle phase. By tracing how that episodic, deformable lid may have regulated heat, recycled chemicals, and sculpted continents, I can start to see a new roadmap for the search for life that stretches from our solar system to the most exotic exoplanets.

From rigid plates to a pliable past

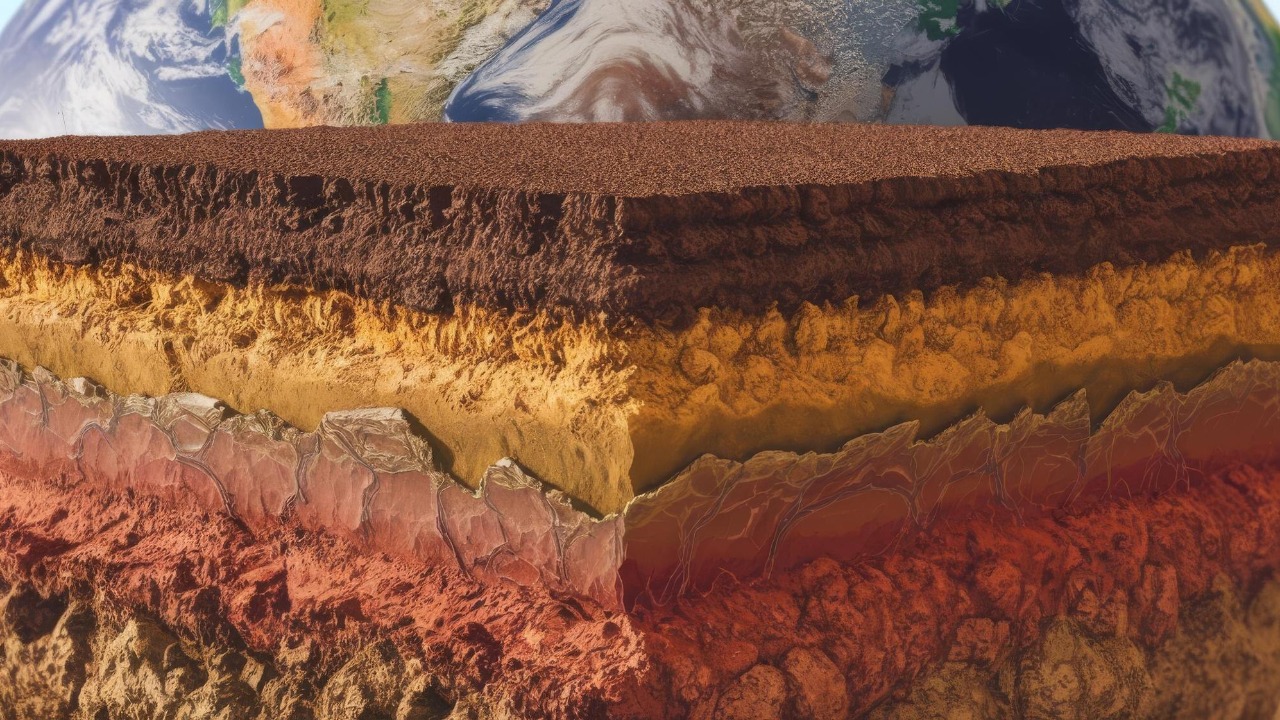

For decades, I have been taught to think of Earth’s surface as a set of rigid plates sliding over a convecting mantle, but the new “episodic squishy lid” framework argues that this familiar picture is only the latest act in a longer tectonic story. In this view, the young planet did not jump straight from a magma ocean to modern plate tectonics, it passed through a stage where the outer shell was mechanically weak, deforming in fits and starts rather than along clean plate boundaries. That intermittent behavior, with periods of sluggish motion punctuated by bursts of activity, offers a way to reconcile evidence of early crustal recycling with the absence of clear plate signatures in the oldest rocks.

Researchers describe this regime as a kind of crown‑like pattern of deformation, where the surface buckles and fractures around upwelling plumes instead of breaking into long‑lived plates. The idea is that as Earth cooled, this squishy lid gradually stiffened, allowing plate tectonics to emerge from a more chaotic, plume‑dominated past. That striking new framework does not just rewrite our own geologic history, it also supplies a template for how rocky planets might evolve from stagnant shells to fully mobile surfaces.

What “episodic squishy lid” really means

When I call this ancient shell “squishy,” I am not suggesting Earth once had a literal soft crust you could press with a finger. The phrase is shorthand for a lithosphere that was warm, weak, and prone to short‑lived bursts of deformation instead of the continuous, organized motion that defines modern plates. In an episodic squishy lid regime, the outer layer can periodically founder into the mantle, driven by density contrasts and plume activity, then lock up again as heat is lost and stresses relax, a stop‑start rhythm that still manages to shuffle material between surface and interior.

This intermittent style of tectonics matters because it can still move heat and chemicals around, even if it lacks the clean geometry of subduction zones and mid‑ocean ridges. The new modeling work suggests that such a regime can persist for long stretches of planetary history, with the lid cycling between more mobile and more stagnant phases as internal heat wanes. By framing those cycles as a natural stage in planetary evolution, the Scientists who identified Earth’s episodic squishy lid argue that many rocky worlds could pass through a similar phase without ever developing textbook plate tectonics.

Why a pliable lid matters for habitability

From a habitability standpoint, what counts is not whether a planet’s tectonics look like Earth’s today, but whether its surface and interior can exchange heat and volatiles over billions of years. A squishy, episodic lid can still drag carbon‑rich crust downward, vent fresh gases through volcanism, and reshape continents, all of which feed into climate regulation and nutrient cycling. If that process operates in pulses, it might produce long stretches of relative stability punctuated by geologic upheavals, a pattern that could still support the slow rise of complex chemistry and, eventually, biology.

That perspective dovetails with broader thinking about how life emerges and persists. During the long window in which a planet cools and its tectonic style evolves, its host star must remain stable enough to provide a consistent energy source so that complex organisms can not only survive but thrive and evolve toward greater complexity, as highlighted in discussions of how During planetary evolution, stellar behavior shapes the odds of civilization. A world with an episodic squishy lid under a calm star might therefore be a better long‑term home for life than a perfectly rigid planet orbiting a volatile sunlike star.

Venus, Earth, and the tectonic fork in the road

Comparing Earth with its near twin Venus shows why this middle ground in tectonic behavior is so important. Although Venus is roughly the same size as Earth, with similar bulk composition and gravity, it lacks clear evidence of plate tectonics and instead displays a surface dominated by volcanic plains, coronae, and other signs of a stagnant or episodically resurfaced lid. That divergence suggests that small differences in cooling history, water content, or internal heat flow can push otherwise similar planets down very different tectonic paths.

In that context, the episodic squishy lid concept offers a way to understand how two sibling worlds could end up so different. If Although Venus may have spent much of its history in a stagnant or episodic regime without ever transitioning to fully mobile plates, Earth appears to have used its own squishy phase as a bridge toward the tectonic engine that now drives its carbon cycle. That fork in the road is a cautionary tale for exoplanet hunters: two worlds can look nearly identical in size and mass yet occupy very different tectonic and climatic states.

Rethinking the “Earth twin” in exoplanet searches

For years, astronomers have framed the search for life in terms of finding planets that look as much like modern Earth as possible, with similar sizes, orbits, and presumed surface conditions. Traditionally, the search for life on exoplanets has been primarily directed towards habitable planets similar to the Earth, orbiting within a narrow habitable zone where liquid water could exist. That strategy made sense when data were sparse, but it risks overlooking worlds that are habitable in less familiar ways, including those caught in transitional tectonic states.

The episodic squishy lid framework nudges me to broaden that target list. Instead of insisting on fully developed plate tectonics, I can consider planets whose mass, age, and internal heat suggest they might be in a pliable‑lid phase that still supports active volcanism and partial recycling. Coupled with new ideas like Hycean worlds, which expand habitability to planets with deep oceans and hydrogen‑rich atmospheres, this shift moves the field away from a narrow “Earth clone” mindset toward a more nuanced catalog of planetary life chances.

How a squishy lid shapes climate and oceans

Climate stability is one of the quiet achievements of Earth’s geologic engine, and a squishy lid may have played a role in establishing that balance before modern plates took over. Intermittent subduction and plume‑driven overturn can still bury carbonates and release greenhouse gases, creating a rough feedback loop between volcanic outgassing and weathering that keeps surface temperatures within a range where liquid water can persist. In the deep past, that may have been enough to prevent runaway glaciations or greenhouse states while the young Sun was dimmer and the atmosphere more volatile.

Oceans, too, are shaped by how the crust flexes and founders. A pliable lithosphere can more easily form basins, uplift proto‑continents, and recycle hydrated rocks, all of which influence sea level and salinity over geologic time. If Earth’s early squishy lid helped maintain long‑lived oceans, then similar regimes on other planets could sustain surface or subsurface seas even without the crisp plate boundaries we see on modern Earth, expanding the range of worlds where stable water reservoirs, and therefore potential biospheres, might endure.

Reading squishy lids from light‑years away

The challenge, of course, is that I cannot directly watch plates move on a planet dozens of light‑years away. Instead, astronomers infer interior behavior from bulk properties like mass and radius, atmospheric composition, and indirect signs of volcanism. A planet slightly larger than Earth with a thick atmosphere rich in volcanic gases might be a candidate for an episodic squishy lid, especially if its age suggests it is still shedding internal heat vigorously. Repeated detection of transient plumes or hot spots, as telescopes improve, could further hint at a surface that deforms in bursts rather than along fixed plate boundaries.

In practice, that means combining models of planetary cooling with spectral fingerprints of gases such as carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and water vapor to sketch out plausible tectonic regimes. If a world shows signs of active outgassing but lacks the strong weathering signatures expected from a fully mobile crust, it might sit in that intermediate squishy state. Over time, building a statistical sample of such planets will help test whether Earth’s path from pliable lid to plate tectonics is common or a cosmic outlier, and whether that path correlates with the presence of life‑friendly atmospheres.

Squishy lids, Hycean worlds, and the next frontier

As I weigh this new tectonic framework against the expanding zoo of exoplanets, it is clear that habitability is less a single recipe and more a menu of overlapping possibilities. Hycean planets, with their deep global oceans and hydrogen‑rich skies, already challenge the idea that only rocky, temperate, Earth‑like worlds can host life. Adding episodic squishy lids to the mix suggests that even within the rocky category, there are multiple viable routes to a dynamic, life‑supporting surface, from fully mobile plates to intermittently deforming shells that still circulate heat and chemicals.

For mission planners and telescope designers, that means prioritizing instruments that can tease out subtle clues about interior activity, not just basic size and orbit. Spectrographs tuned to volcanic gases, time‑series observations that can catch transient plumes, and models that link those signals to underlying tectonic styles will all be crucial. If Earth’s own squishy past is any guide, the most promising homes for life may not be perfect Earth twins, but worlds caught in the act of stiffening their lids, poised between chaos and order in the long evolution of a living planet.

More from MorningOverview