Jupiter turns familiar weather into something almost alien, and nowhere is that more obvious than in its lightning. The giant planet’s storms unleash electrical bolts that carry up to one hundred thousand times more energy than a typical flash on Earth, revealing an atmosphere far more extreme than the thunderheads we watch from our windows. I want to unpack how scientists measured that staggering power, what it tells us about Jupiter’s deep weather engine, and why those distant flashes are reshaping how we think about storms across the Solar System.

How scientists measured Jupiter’s monster bolts

To understand how Jupiter’s lightning can dwarf Earth’s, I first need to look at how researchers actually measure a flash on a world no probe has ever landed on. Instead of counting strikes from the ground, scientists rely on spacecraft that detect radio bursts and high-energy emissions produced when a bolt rips through Jupiter’s atmosphere. By comparing the strength and frequency of those signals with well-studied lightning on Earth, they can estimate how much power each Jovian flash carries and how long it lasts, then scale that to total energy using established models of electrical discharges in gases that match Jupiter’s composition and pressure profile, as documented in Jupiter lightning radio data and Juno lightning detections.

Those measurements show that individual Jovian bolts can reach energies up to 1012 joules, compared with roughly 107 to 108 joules for a typical terrestrial flash, which is where the “100,000 times” comparison comes from. The key is that Jupiter’s lightning often spans much longer paths through denser, deeper clouds, so the discharge has more distance and material to energize before it dissipates. When I line up the spacecraft radio signatures with optical flashes and thermal emissions, the picture that emerges is of a storm system where a single bolt can rival the total energy output of a small power plant running for hours, a conclusion supported by combined analyses of Jovian optical flashes and Juno radio-frequency bursts.

Why Jupiter’s atmosphere supercharges storms

The raw power of Jupiter’s lightning starts with the planet’s sheer scale and atmospheric depth. Unlike Earth, which has a relatively thin weather layer, Jupiter’s atmosphere extends thousands of kilometers downward, with pressure and temperature climbing steadily as you go deeper. That vertical stack of cloud decks, from ammonia ice at the top to water and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide layers below, creates a vast region where rising plumes and sinking downdrafts can separate electrical charges over enormous distances, a structure mapped in detail by Jupiter atmospheric profiles and cloud-layer models.

On top of that depth, Jupiter’s rapid rotation and intense internal heat drive ferocious convection that feeds its storms from below rather than just from sunlight at the top. The planet radiates more energy than it receives from the Sun, so hot material continually rises from the interior, punching through the upper cloud decks and creating towering thunderheads that can span thousands of kilometers. In that environment, charge separation can build to levels far beyond what Earth’s smaller, cooler cumulonimbus clouds can sustain, which helps explain why Jovian lightning can reach such extreme energies according to internal heat studies and Juno convection observations.

Juno’s close-up view of alien lightning

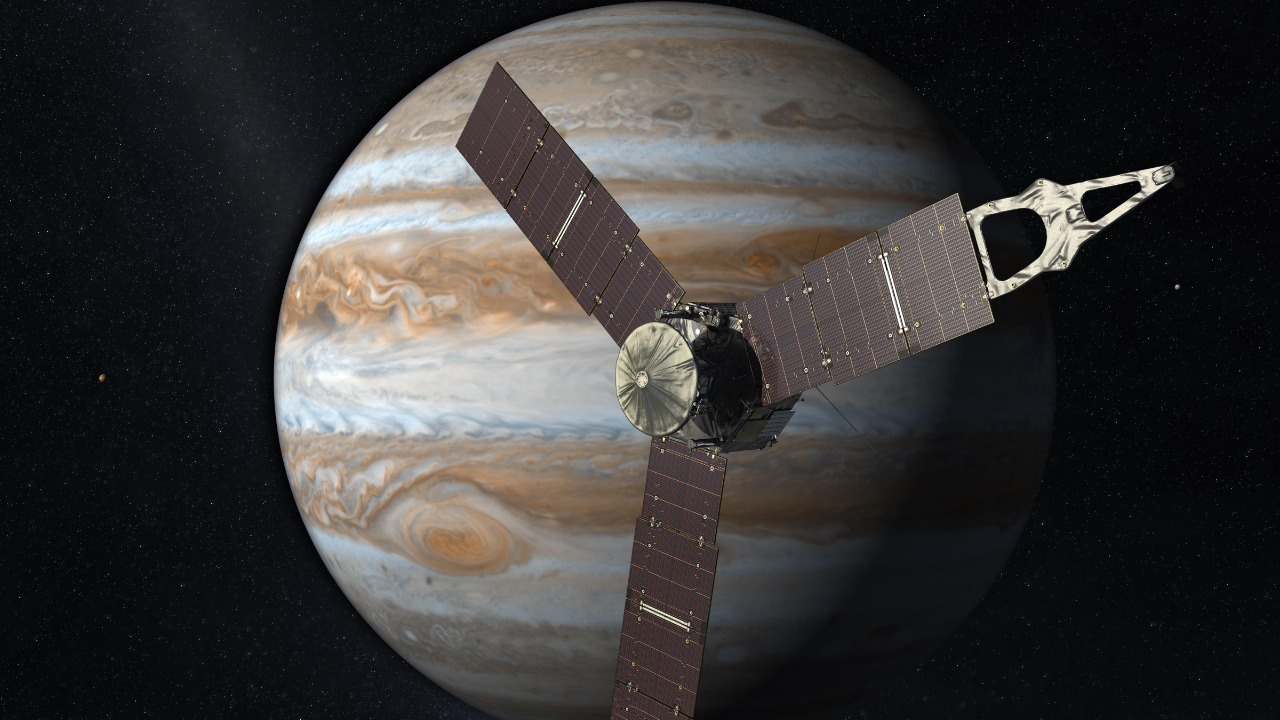

The turning point in our understanding of Jupiter’s lightning came when NASA’s Juno spacecraft began looping over the planet’s poles on a highly elliptical orbit. Flying just a few thousand kilometers above the cloud tops, Juno’s instruments could finally pick up high-frequency radio emissions and optical flashes that earlier missions missed, especially in the polar regions where storms cluster. I see that as a shift from treating Jovian lightning as a distant curiosity to analyzing it as a detailed data set, with Juno’s Microwave Radiometer and Waves instrument capturing signatures that match and then exceed the strongest terrestrial storms, as shown in Juno lightning results and polar flash detections.

Juno’s measurements revealed that most lightning activity occurs at high latitudes, not near the equator as on Earth, and that the flashes often originate deeper in the atmosphere, near the water-cloud layer where pressures are several times higher than at Earth’s surface. That depth means each discharge can tap into a thicker column of charged particles, which helps explain the extraordinary energies inferred from the radio and optical data. When I compare Juno’s findings with earlier observations from Voyager and Galileo, the newer data show that we had been underestimating both the frequency and intensity of Jovian lightning, a correction supported by cross-mission analyses in radio-wave archives and optical flash catalogs.

How Jovian bolts stack up against Earth’s lightning

When I put Jupiter’s lightning side by side with Earth’s, the contrast is stark but also surprisingly structured. On Earth, a typical cloud-to-ground flash carries on the order of 107 to 108 joules, with peak currents of tens of kiloamperes and channel lengths of a few kilometers, values that have been measured extensively by ground-based networks and aircraft campaigns. Jupiter’s flashes, by comparison, can reach energies up to 1012 joules and span hundreds of kilometers, which is where the estimate of up to 100,000 times more energy comes from, as synthesized in comparative studies that draw on Earth lightning statistics and Jovian energy estimates.

Yet the underlying physics is not entirely alien. Both planets rely on the same basic mechanism of charge separation in convective clouds, with ice particles and droplets colliding and exchanging charge until the electric field becomes strong enough to break down the surrounding air or gas. What changes on Jupiter is the scale and the environment: higher pressures, different gas composition, and deeper convection all allow the electric field to build over longer distances and sustain more powerful discharges. That is why researchers can use Earth-based models of lightning as a starting point, then adjust them for Jovian conditions to match the spacecraft data, a method described in cloud microphysics models and storm-structure analyses.

What lightning reveals about Jupiter’s hidden water

For planetary scientists, the real prize in studying Jupiter’s lightning is not just the spectacle but the clues it offers about water deep inside the planet. On Earth, the most intense lightning forms in clouds that contain liquid water and ice, where collisions between particles efficiently separate charge. The same principle appears to hold on Jupiter, which means that detecting strong lightning is indirect evidence for significant water content in the layers where those storms form. Juno’s instruments have used that logic to map where lightning occurs and then infer how much water must be present at those depths, a strategy detailed in Jupiter water measurements and microwave sounding data.

Those analyses suggest that Jupiter’s equatorial regions contain water at levels comparable to or higher than what some formation models predicted, while the distribution at higher latitudes is more complex. Because water is a key ingredient in theories about how the giant planets formed and how they captured their massive envelopes of hydrogen and helium, lightning effectively becomes a probe of Jupiter’s origin story. When I connect the dots between lightning locations, microwave signatures, and gravity-field measurements, the emerging picture is of a planet whose deep atmosphere is more heterogeneous than once thought, a conclusion supported by combined interpretations in Juno science results and water abundance studies.

Storm belts, hot spots, and the Great Red Spot

Jupiter’s lightning does not strike randomly across its banded face, and that pattern helps decode the planet’s broader weather system. Most flashes cluster in the turbulent belts and zones where jet streams collide, especially in regions where bright, towering clouds punch through the surrounding atmosphere. These stormy corridors often line up with so-called “hot spots” in infrared images, where gaps in the upper clouds allow heat from below to escape, a relationship documented in infrared hot-spot maps and belt-and-zone analyses.

The Great Red Spot, Jupiter’s most famous storm, adds another layer to the story. Although it is a gigantic anticyclonic vortex, its lightning activity appears to be more subdued than in some of the smaller, more vigorous convective storms that pop up around it. That contrast suggests that the Great Red Spot may be more of a long-lived, high-altitude circulation feature, while the most intense lightning is tied to deep, rising plumes that tap into the water-cloud layer. When I compare lightning maps with high-resolution images of the Great Red Spot and nearby storms, the data support the idea that Jupiter’s most powerful electrical activity is concentrated in transient, vertically developed systems rather than in the iconic red oval itself, as indicated by combined imaging and radio studies in Great Red Spot interior scans and storm-flash correlations.

Implications for exoplanets and brown dwarfs

Jupiter’s supercharged lightning is not just a local curiosity, it is also a template for understanding weather on giant planets orbiting other stars. Many exoplanets discovered so far are gas giants that are hotter, more massive, or more strongly irradiated than Jupiter, which suggests that their storms could be even more energetic. If lightning on Jupiter already reaches energies up to 1012 joules, then similar or stronger discharges on exoplanets might produce detectable radio bursts or optical flashes that future telescopes could pick up, an idea explored in theoretical work that builds on Jovian lightning energetics and radio-emission models.

The same reasoning extends to brown dwarfs, objects that sit between planets and stars in mass and often have thick, cloudy atmospheres. Observations of variable infrared and radio emissions from some brown dwarfs have already hinted at dynamic weather, and Jupiter’s lightning provides a nearby example of how deep convection and strong magnetic fields can combine to produce powerful bursts. When I connect the behavior of Jovian storms with these distant signals, it becomes plausible that lightning-like discharges are common across a wide range of substellar atmospheres, a possibility that researchers are actively testing using models calibrated against Jupiter atmospheric data and Juno storm observations.

Hazards and opportunities for future missions

For any spacecraft that will venture into Jupiter’s atmosphere or skim close to its cloud tops, the planet’s extreme lightning is both a hazard and a scientific opportunity. High-energy discharges can generate intense electromagnetic pulses and energetic particles that threaten sensitive electronics, especially during close passes through stormy regions. Mission planners for Juno and proposed future probes have had to account for these risks by hardening instruments, choosing trajectories that minimize exposure, and timing observations to balance safety with the need to sample active storms, as described in mission design documents that draw on Juno’s radiation strategy and entry-probe concepts.

At the same time, lightning offers a rare window into layers of Jupiter’s atmosphere that are otherwise difficult to probe directly. A future entry probe equipped with dedicated lightning detectors and high-speed cameras could measure the local electric fields, particle sizes, and water content right where the discharges occur, turning each flash into a diagnostic tool. I see that as a natural next step after Juno’s remote sensing, one that would build on the existing maps of lightning activity and target the most scientifically rich regions, a path outlined in studies that combine microwave sounding with flash-location catalogs to identify promising entry corridors.

What Jupiter’s lightning teaches us about weather everywhere

When I step back from the numbers, Jupiter’s colossal lightning underscores a broader point about weather across the Solar System. The same basic ingredients that drive storms on Earth, such as convection, moisture, and charge separation, can scale up dramatically in different environments, producing phenomena that are familiar in outline but extreme in detail. By studying how those processes play out under Jupiter’s higher pressures, deeper clouds, and stronger internal heat, scientists refine the physical models that also describe thunderstorms on our own planet, a cross-pollination that is evident in work that uses Earth lightning data alongside Jovian storm measurements.

That feedback loop runs in both directions. Insights from Jupiter help researchers test how robust their theories are, while advances in terrestrial meteorology improve the tools used to interpret spacecraft observations. In that sense, every time a Jovian storm unleashes a bolt with one hundred thousand times the energy of a typical Earth flash, it is not just a display of raw power but a natural experiment in atmospheric physics. By reading those signals carefully, using the growing archive of Juno science results and Jupiter atmospheric profiles, I can see how a distant gas giant is quietly sharpening our understanding of weather from our own skies to the farthest exoplanets we can detect.

More from MorningOverview