Liquid metals that flow like water yet conduct electricity like solid wires are moving from lab curiosities into the toolkit for next‑generation devices. Researchers are learning to sculpt, pattern, and program these alloys in ways that could change how I think about building everything from flexible wearables to adaptive robots and reconfigurable computers.

Instead of treating circuitry as a fixed skeleton buried inside a gadget, engineers are starting to imagine electronics that can stretch, heal, and even rearrange themselves on demand. That shift, if it holds, would blur the line between hardware and material, turning the body of a device into an active, shape‑shifting platform for sensing and computation.

Why liquid metal is suddenly back in the spotlight

Liquid metal has long carried a sci‑fi aura, but the renewed attention is rooted in practical engineering rather than movie imagery. Alloys based on gallium can stay liquid at room temperature, carry high currents, and wet many surfaces, which makes them unusually well suited to the flexible, skin‑like electronics that rigid copper traces cannot easily support. I see the appeal in simple terms: instead of forcing soft devices to accommodate hard components, these materials let the electronics themselves become soft without giving up performance.

What is changing now is not just the chemistry, but the mindset around how to use it. Designers are starting to treat liquid metal as a way to preserve “optionality” in hardware, keeping pathways open so circuits can be rerouted or upgraded later rather than locked in at manufacture. That philosophy echoes the broader idea of building systems that can survive and thrive in volatile conditions by keeping multiple futures available, a theme explored in depth in work on strategic optionality and resilience.

From rigid boards to soft, stretchable circuits

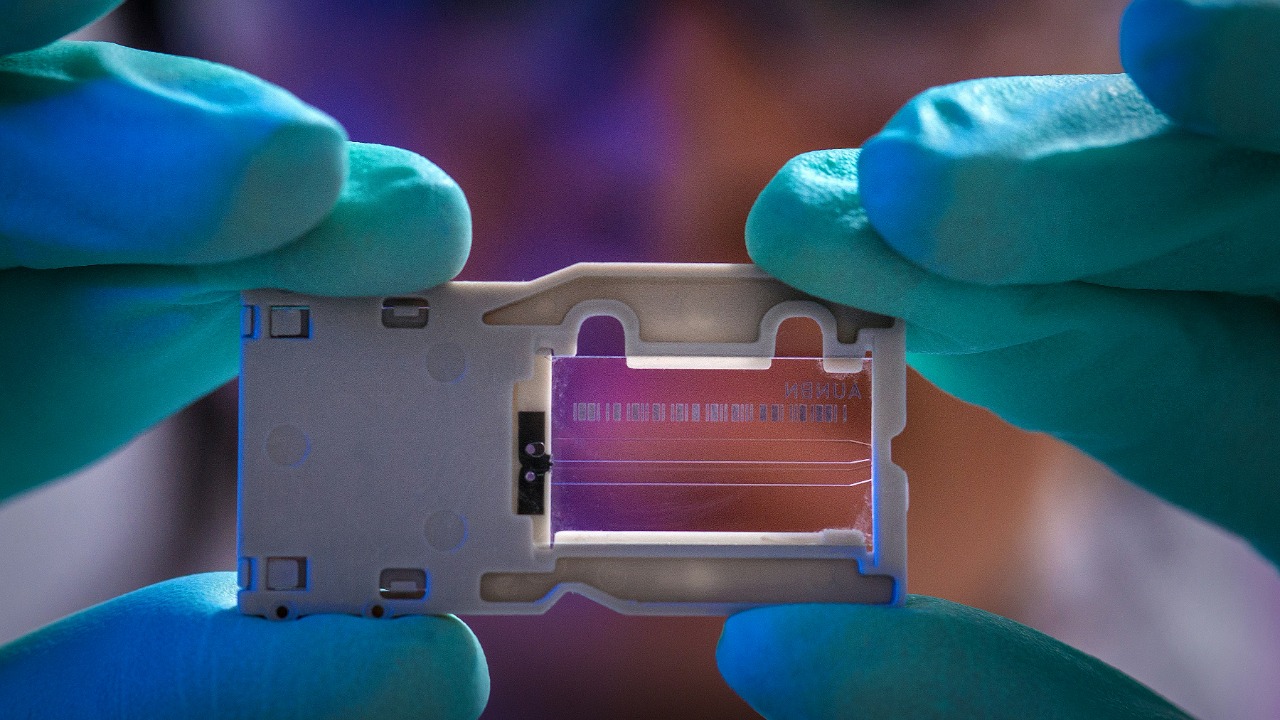

Traditional printed circuit boards are optimized for stability, not movement, which is why a smartphone can tolerate drops but not being bent in half. Liquid metal circuits flip that trade‑off by embedding conductive channels inside elastomers or textiles, so the wiring can stretch and twist with the material around it. In practice, that means a sensor array can be laminated onto a joint, a throat, or a beating heart without the fatigue cracks that plague thin copper films.

I see this as a shift from designing around constraints to designing with them. Instead of fighting the fact that bodies, clothes, and soft robots deform constantly, engineers can route liquid metal traces along paths that anticipate strain and even exploit it. When a sleeve stretches during a tennis serve or a rehabilitation exercise, the changing geometry of those channels can be read as a signal rather than treated as noise, turning motion into data instead of damage.

Self‑healing and reconfigurable wiring

One of the most intriguing tricks of liquid metal is its ability to restore conductivity after being cut or punctured. When a channel inside a soft substrate is severed, the alloy can flow back together, re‑forming a continuous path once the material relaxes or is pressed back into place. That self‑healing behavior is not magic, it is fluid dynamics, but it opens the door to devices that tolerate abuse in ways rigid electronics simply cannot.

Reconfigurability goes a step further. Because the conductive phase is mobile, it is possible to imagine circuits that can be “rewired” by moving droplets, changing pressure patterns, or applying electric fields that reshape the network. In effect, the layout of the hardware becomes a variable rather than a constant, which aligns with a broader push in computing to treat structure as something that can be optimized on the fly instead of frozen at design time.

What liquid metal could mean for wearables and health tech

Wearable devices are the most obvious beneficiaries of this shift, because the human body is a hostile environment for brittle electronics. Smartwatches and fitness bands already push the limits of what rigid boards can do on curved surfaces, but they still rely on hard modules tucked into relatively stiff housings. Liquid metal circuits, by contrast, can be printed or injected into thin films that conform to skin like a temporary tattoo, enabling continuous monitoring without the bulk or chafing of current gear.

In medical settings, that same conformability could support long‑term electrophysiology, respiratory tracking, or muscle monitoring in patients who cannot tolerate rigid electrodes. I can imagine intensive‑care sensors that wrap gently around a limb or chest, maintaining stable contact as swelling, posture, or breathing patterns change. The promise is not just comfort, but data quality, since a sensor that moves with the tissue it measures is less likely to lose contact or introduce artifacts.

Soft robots and shape‑shifting machines

Soft robotics is another field where liquid metal feels less like a novelty and more like a missing piece. Inflatable grippers, tentacle‑like manipulators, and crawling robots built from silicone or fabric need embedded sensing and actuation that can survive large deformations. Conventional wires either limit their motion or fail quickly, which is why many prototypes still rely on external tethers. Liquid metal channels, cast directly into the robot’s body, can deliver power and signals while flexing as freely as the surrounding material.

That integration changes how I think about the boundary between structure and control. When the same soft limb that touches an object also carries the circuitry that interprets that touch, the robot can respond more locally and gracefully. Over time, that could lead to machines whose bodies adapt their stiffness, grip, or gait by redistributing liquid metal within internal networks, effectively re‑plumbing their own nervous systems to suit the task at hand.

Programming materials like code

As liquid metal circuits become more complex, the challenge is no longer just fabricating them, but describing and controlling their behavior. There is a growing push to treat patterns of conductive and insulating regions as a kind of physical “code,” where the layout encodes logic, sensing, or communication functions. That perspective borrows heavily from how computer scientists think about tokens and sequences in language models, where meaning emerges from patterns rather than individual symbols.

In that context, it is striking to see researchers draw on tools originally built for text, such as character‑level vocabularies used in models like CharacterBERT, to reason about how small building blocks combine into larger functional motifs. The analogy is not perfect, but it is useful: just as a neural network learns which character strings form valid words, a design system for liquid metal could learn which micro‑geometries yield reliable stretchable interconnects, antennas, or sensors under different mechanical loads.

Designing with patterns, not just parts

Once hardware is framed as a language of patterns, the design process starts to look less like drafting a schematic and more like composing a sentence. Engineers can think in terms of recurring “phrases” of geometry that achieve specific behaviors, then arrange and remix them to suit a new application. That mindset encourages libraries of reusable motifs rather than one‑off layouts, which in turn makes it easier to share, audit, and improve designs over time.

There is a parallel here with how collaborative knowledge systems catalog and replicate useful structures. Collections of frequently reused patterns and words in software and documentation show how communities converge on stable building blocks that can be combined in countless ways. I expect a similar convergence in liquid metal design, where certain channel shapes, junctions, and sensor geometries become the “most replicated” elements across many devices because they balance performance, manufacturability, and robustness.

Risk, resilience, and the messy reality of new materials

For all the promise, liquid metal is not a free upgrade to every gadget. Gallium alloys can corrode some metals, oxidize at their surface, and behave unpredictably if the surrounding substrate is damaged or contaminated. Manufacturing at scale is also nontrivial, since injecting or printing precise microchannels into soft materials demands tight process control. I find it useful to treat these constraints not as deal‑breakers, but as parameters that must be built into any realistic roadmap.

That is where the earlier notion of optionality becomes more than a buzzword. By designing devices that can tolerate partial failure, reroute around damaged regions, or be reconfigured in the field, engineers can hedge against the uncertainties that come with a young technology. The goal is not to eliminate risk, but to structure it so that a crack in one part of a circuit does not doom the entire system, and so that new fabrication methods can be adopted incrementally rather than in a single, brittle leap.

Where the research frontier really stands

Despite the excitement, it is important to be clear about what is verified and what remains speculative. Many of the most eye‑catching demonstrations of liquid metal devices still live in controlled lab environments, with carefully prepared samples and limited lifetimes. Claims about fully self‑healing, endlessly reconfigurable consumer gadgets are, at this point, unverified based on available sources, and should be treated as aspirations rather than imminent products.

At the same time, the broader ecosystem around programmable materials is maturing in ways that support this line of work. Researchers are building shared vocabularies, pattern libraries, and design tools that make it easier to reason about complex systems, even when some experimental details are sparse or hosted on barebones domains such as specialized project pages. As those tools improve and more data accumulates, I expect the line between “liquid” and “solid” in electronics to look less like a boundary and more like a continuum that designers can navigate with increasing confidence.

More from MorningOverview