Physicists once treated Einstein’s picture of a clockwork universe as the gold standard for what “reality” should look like, with objects carrying definite properties whether or not anyone is watching. A deceptively simple test of that idea, built around a few photons and some clever statistics, forced them to confront the possibility that nature does not play by those rules at all. I want to trace how that test emerged, what it actually measured, and why its fallout now shapes debates far beyond physics, from information theory to the way we model complex systems.

Einstein’s uneasy truce with quantum weirdness

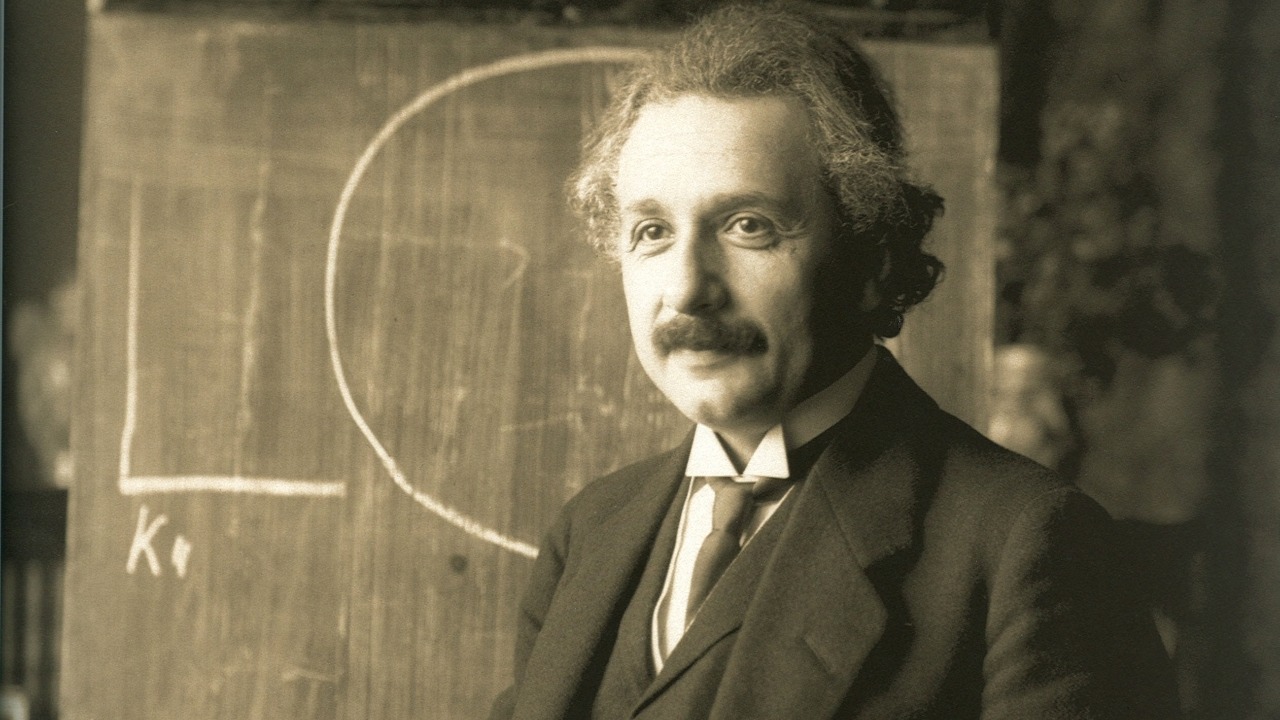

Einstein helped launch quantum theory, yet he never accepted the idea that the world at its core might be governed by chance rather than by hidden facts waiting to be uncovered. In his view, a complete description of reality should assign definite values to physical quantities, even if our instruments cannot access them, and any influence should travel no faster than light. That picture, often called “local realism,” blends two intuitions: that things have properties independent of observation, and that distant events cannot instantly affect one another.

For a time, quantum mechanics and local realism coexisted in an uneasy truce, because the theory’s probabilistic predictions worked spectacularly well while leaving room for the hope that some deeper mechanism might lurk underneath. Einstein and collaborators framed this hope in terms of “hidden variables,” hypothetical parameters that would restore determinism and locality if only we could see them. The tension sharpened as experiments probed ever smaller scales, revealing interference patterns and discrete jumps that looked less like classical ignorance and more like a fundamentally different kind of randomness.

How a thought experiment became a testable inequality

The turning point came when theorists realized that the clash between quantum mechanics and local realism could be distilled into a single, testable inequality. Instead of arguing in the abstract about whether particles “really” have properties before measurement, they focused on correlations between measurements made on entangled pairs. If local hidden variables exist, then there are strict limits on how strongly those outcomes can be correlated once you account for all possible settings and statistical tricks.

That insight transformed a philosophical dispute into an experimental program. The inequality, derived from simple probability rules, does not depend on the details of any particular hidden variable model, only on the assumptions of locality and preexisting values. Quantum mechanics predicts that entangled particles can violate this bound under specific measurement choices, while any locally realistic theory must respect it. The stage was set for a direct confrontation between Einstein’s intuitions and the structure of quantum theory, using a test that could be run in a laboratory rather than in a seminar room.

What the “simple test” actually measures

At the heart of the test is a surprisingly modest setup: pairs of particles are prepared in an entangled state, then sent to two distant detectors where experimenters choose measurement settings and record outcomes. Each side has a small menu of possible measurements, often just two or three, and each outcome is typically binary, such as “spin up” or “spin down.” By repeating this process many times and comparing the joint results, physicists can compute a combination of correlations that, under local realism, must fall within a specific numerical range.

Quantum mechanics predicts that for certain entangled states and measurement angles, the observed correlations will exceed that classical range, violating the inequality. The test does not require exotic machinery beyond precise sources, fast detectors, and careful timing, which is why it is often described as simple in concept even if it is demanding in execution. What it probes is not the particles themselves but the logical structure of any theory that tries to preserve both locality and preexisting properties, and it does so with a single number that either respects or breaks the classical bound.

Why violating local realism shook the foundations

When experiments began to report violations of the inequality consistent with quantum predictions, the implications were stark. If the data are taken at face value, then at least one of Einstein’s guiding principles must give way: either measurement outcomes are not determined by local hidden variables, or influences can propagate in ways that defy classical notions of separation. The test does not tell us which principle to abandon, but it rules out the comforting idea that we can keep both without altering the theory’s predictions.

This forced a rethinking of what “reality” means in physics. Instead of imagining particles as tiny billiard balls carrying definite attributes, many researchers came to view the quantum state as a catalog of potential outcomes that only crystallize when measured. Others leaned into nonlocality, accepting that entangled systems behave as a single whole even when separated by large distances. The simple numerical violation of an inequality thus opened a landscape of interpretations, each sacrificing some piece of classical intuition to preserve the empirical success of quantum mechanics.

From lab curiosity to information resource

As the test became more refined, physicists realized that the same correlations that violate local realism could be harnessed as a resource. Entanglement, once seen mainly as a conceptual puzzle, turned into a practical ingredient for tasks like secure communication and distributed computation. The strength of the nonclassical correlations, quantified by how much they overshoot the classical bound, became a measure of how much advantage quantum systems can offer over classical ones in specific protocols.

This shift reframed the original test from a mere refutation of hidden variables into a benchmark for quantum technologies. When engineers design quantum key distribution schemes or multi-party computation protocols, they often rely on the same statistical structure that underlies the inequality, using it to certify that no classical eavesdropper could reproduce the observed correlations. The experiment that once challenged Einstein’s realism now doubles as a quality check for devices that treat entanglement as an asset rather than an oddity.

Debates over loopholes and experimental rigor

The early rounds of testing did not settle the argument entirely, because critics pointed to potential “loopholes” that might allow local realism to survive. If detectors miss a significant fraction of particles, or if measurement choices are not truly independent of the hidden variables, then the observed violation might be an artifact rather than a genuine refutation. Experimentalists responded by closing these gaps one by one, improving detector efficiencies, separating measurement stations, and randomizing settings with increasing care.

Each refinement tightened the constraints on any theory that tried to preserve Einstein’s picture without contradicting the data. The cumulative effect was not just a stronger empirical case for quantum mechanics, but a new standard for how foundational experiments are conducted. Precision timing, statistical transparency, and explicit accounting for every potential bias became part of the culture, influencing how other sensitive measurements are designed and interpreted across physics.

Spillover into how we model complex systems

The conceptual shock of seeing a simple test overturn a cherished view of reality has resonated beyond quantum physics. In fields that grapple with complex, interdependent systems, researchers have drawn lessons from the way a clean, falsifiable inequality exposed hidden assumptions about locality and determinism. When economists or sustainability experts build models of coupled networks, they increasingly ask which constraints are structural and which are artifacts of classical intuition.

Some frameworks for long term planning now treat uncertainty and interdependence as intrinsic features rather than nuisances to be averaged away. For example, multidisciplinary approaches to sustainable development explicitly model feedback loops between environmental, economic, and social variables, recognizing that local actions can have nonlocal consequences that resemble, in spirit, the entangled correlations seen in quantum tests. One such framework, described in a detailed analysis of sustainable development modeling, treats interconnected indicators as a system whose behavior cannot be reduced to isolated parts, echoing the lesson that simple, global constraints can reveal where classical separability fails.

How the test entered popular and technical culture

Outside specialist circles, the story of a straightforward experiment challenging Einstein’s view of reality has become a touchstone for how science can overturn its own assumptions. Discussions among technologists and scientifically literate readers often use it as a case study in how counterintuitive results can still be robust when backed by clear statistical structure. The test’s reliance on correlations and inequalities makes it accessible to people who work with data in other domains, from software engineering to cryptography.

In online forums where developers and researchers trade insights about quantum computing and security, the implications of violating local realism are dissected alongside practical questions about hardware and algorithms. One widely read thread on quantum foundations illustrates how the test’s logic has seeped into conversations about what kinds of randomness and nonlocality future technologies might exploit. The fact that a few lines of algebra and a careful experimental design can unsettle a century old intuition about reality has turned the inequality into a cultural reference point as much as a technical tool.

Rethinking “reality” without overreaching the data

For all its drama, the test does not tell us which interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, nor does it license sweeping claims about consciousness or free will. What it does, with unusual clarity, is rule out a broad class of locally realistic explanations that would have preserved Einstein’s preferred picture without altering the theory’s predictions. Any further story about what the world is “really like” must respect that constraint, or else contradict the data that the inequality so cleanly summarizes.

As I see it, the enduring power of this simple test lies in how it balances ambition and humility. It reaches deep into our assumptions about separability and determinism, yet it does so through a concrete, repeatable procedure that anyone with the right equipment can scrutinize. In that sense, it offers a model for how physics can confront its own metaphysical baggage: by turning vague intuitions into sharp, testable statements, then letting the world answer in the language of numbers rather than nostalgia.

More from MorningOverview