Earth’s magnetic bubble, the invisible shield that normally deflects charged particles from the Sun, briefly shrank to a fraction of its usual size during a recent superstorm, exposing satellites and navigation systems to a level of space weather stress that scientists had only modeled on paper. The collapse, driven by an extreme burst of solar plasma, compressed the planet’s plasma environment by roughly 78 percent and pushed critical infrastructure such as GPS, communications satellites, and power grids closer to a dangerous edge. I want to unpack what actually happened, why the numbers are so stark, and how close we came to a cascading failure of the systems that quietly run modern life.

How a rare solar superstorm crushed Earth’s plasma shield

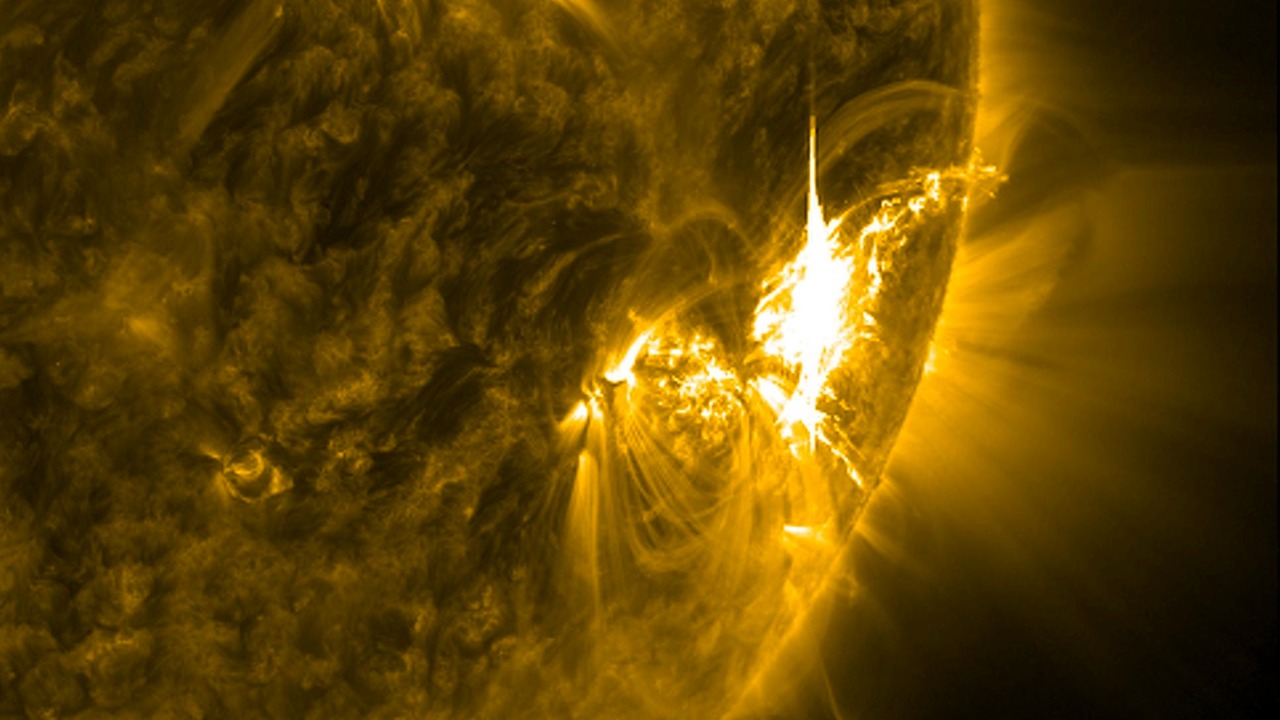

The starting point is the Sun itself. Earlier this year, a powerful eruption of magnetized plasma blasted out from an active region on the solar surface and slammed into Earth’s magnetic field with unusual force. Instead of simply rattling the magnetosphere, the incoming cloud of charged particles and embedded magnetic fields drove a deep geomagnetic disturbance that compressed the planet’s plasma shield to a historic low, a collapse that researchers later quantified as a roughly 78 percent reduction in its usual extent based on detailed satellite measurements described in new analysis. In practical terms, the protective bubble that normally stretches tens of thousands of kilometers into space was squeezed inward, leaving satellites that usually orbit safely inside it suddenly exposed to harsher conditions.

What makes this event stand out is not just the intensity of the solar storm but the way it coupled with Earth’s magnetic field. The interplanetary magnetic field embedded in the solar plasma aligned in a way that maximized energy transfer into the magnetosphere, a configuration that space physicists have long warned could trigger an extreme geomagnetic storm. As the storm unfolded, instruments on multiple spacecraft recorded a rapid drop in the density and extent of the plasma environment that surrounds the planet, confirming that the magnetosphere had been compressed far beyond typical storm behavior, a result that was later detailed in a comprehensive study of the massive geomagnetic superstorm.

What “78 percent smaller” really means for the magnetosphere

When scientists say Earth’s plasma shield shrank by about 78 percent, they are not talking about a subtle fluctuation. The magnetopause, the outer boundary where the planet’s magnetic field meets the solar wind, was driven inward so far that it approached or even dipped inside the orbits of satellites that normally operate in relatively benign conditions. According to the storm reconstructions, the compressed magnetosphere left a much thinner buffer between the high-energy particles of interplanetary space and the spacecraft that carry everything from weather sensors to broadband relays, a scenario that researchers highlighted in their modeling of the severe compression of Earth’s magnetic bubble.

In practice, a 78 percent reduction in the size of the plasma shield means that regions of space that are usually well within the magnetosphere’s protection suddenly became part of the storm’s front line. Satellites in medium and high Earth orbits, which include many navigation and communications platforms, found themselves in an environment with higher radiation levels, more energetic particles, and stronger electrical currents than they were designed to handle on a routine basis. The event effectively turned a large swath of near-Earth space into a temporary extension of the solar wind, a transformation that was documented in detail in a multi-satellite reconstruction of how the magnetosphere was crushed during the peak of the storm.

Inside the storm: satellite data that revealed the collapse

The scale of the collapse only became clear because a constellation of spacecraft happened to be in the right places at the right times. As the solar plasma cloud swept past Earth, satellites measuring magnetic fields, charged particle fluxes, and plasma densities recorded abrupt shifts that did not match the patterns of more familiar geomagnetic storms. When researchers later stitched together these readings, they found that the magnetopause had lurched inward far more dramatically than standard models predicted, a conclusion that emerged from the detailed reconstruction of the superstorm’s impact on the magnetosphere.

Those satellite records also showed how quickly the system changed. Within a relatively short window, the outer boundary of the magnetosphere moved inward by tens of thousands of kilometers, then oscillated as the storm evolved, exposing different orbital regions to fluctuating levels of radiation and electrical disturbance. The data set, which drew on multiple spacecraft in different orbits, allowed scientists to track not just the minimum size of the plasma shield but the dynamic way it responded to the storm’s changing pressure and magnetic orientation, a level of detail that underpins the current understanding of how the huge solar storm reshaped near-Earth space.

Why GPS and navigation systems were suddenly vulnerable

For anyone who relies on GPS, from airline pilots to ride-hailing apps, the most immediate concern is what such a storm does to navigation signals. GPS satellites orbit in medium Earth orbit, a region that sits between low Earth orbit and the geostationary belt and that is usually shielded by the magnetosphere. When the plasma bubble shrank, those satellites were pushed closer to the boundary where the solar wind’s charged particles and magnetic fields can directly interfere with radio transmissions. That exposure increases the risk of signal scintillation, timing errors, and even temporary outages, a vulnerability that space weather specialists have been warning about in the context of extreme solar storms that compress Earth’s shield.

The storm’s impact on the ionosphere, the charged upper layer of the atmosphere through which GPS signals must pass, added another layer of risk. As energetic particles poured into the compressed magnetosphere, they altered the ionospheric density and structure, creating irregularities that can bend, delay, or scatter the radio waves used by navigation systems. For high-precision applications such as aircraft approaches, precision agriculture, and timing for financial networks, even small disruptions can cascade into operational headaches. The superstorm effectively tested the resilience of GPS and similar systems under conditions that approach worst-case scenarios, highlighting how a future event of comparable or greater intensity could push navigation infrastructure beyond its current design margins.

From power grids to pipelines: cascading risks on the ground

The drama of a crushed plasma shield plays out in space, but the consequences do not stay there. When the magnetosphere is compressed and disturbed, it drives strong currents in the upper atmosphere that in turn induce electrical currents in long conductors on the ground, including power lines, pipelines, and undersea cables. During the recent superstorm, operators of high-voltage networks had to watch for geomagnetically induced currents that can overheat transformers, trip protective relays, and in extreme cases trigger widespread blackouts, a risk that has been repeatedly underscored in analyses of how storms that shrink the magnetosphere can stress terrestrial infrastructure.

Beyond the power grid, other systems are vulnerable in more subtle ways. Pipelines can experience accelerated corrosion when geomagnetic storms drive fluctuating currents through their metal structures, while long-distance communication cables can see induced voltages that interfere with signal repeaters. Aviation routes that rely on high-frequency radio over polar regions may have to be diverted when the ionosphere is disturbed, adding fuel costs and logistical complexity. The recent event did not trigger a catastrophic failure, but it served as a live demonstration of how a deeply compressed magnetosphere can set off a chain of stresses that ripple from orbit down to the most mundane parts of industrial infrastructure.

How long the shield stayed weakened and what that window meant

One of the more unsettling aspects of the superstorm was not just how far the plasma shield collapsed but how long it remained in a weakened state. Instead of snapping back quickly once the initial shock passed, the magnetosphere took days to fully recover, leaving satellites and ground systems operating under elevated risk for an extended period. Accounts of the event describe Earth’s protective environment as being compromised for nearly a week, a timeframe echoed in reports that the protective shield collapsed for nearly a week during the height of the storm’s impact.

That prolonged vulnerability matters because many mitigation measures are designed around short-lived spikes rather than multi-day stress. Power grid operators can temporarily reconfigure networks, satellite controllers can switch spacecraft into safe modes, and airlines can reroute flights for a limited window. When the hazard persists, those stopgap measures become harder to sustain without disrupting normal operations. The extended recovery period in this case forced operators and policymakers to confront a scenario in which space weather is not a brief shock but a drawn-out siege, raising questions about how to maintain resilience if a future storm of similar or greater intensity lingers even longer.

Public alarm, social media exaggeration, and what the data actually show

As news of the storm spread, social media filled with dramatic claims that Earth’s shield had “collapsed” or that the planet had been left almost completely unprotected. Some posts described the event in apocalyptic terms, suggesting that the magnetosphere had effectively vanished and that only luck prevented a technological catastrophe. One widely shared account framed the episode as a solar storm that had “officially crushed” the plasma shield, language that captured public anxiety but glossed over the nuances of how the magnetosphere actually behaves, as seen in posts that circulated about a solar storm crushing Earth’s shield.

The scientific record tells a more precise story. The magnetosphere did not disappear, but it was compressed to a historically small size, and that distinction matters. A shrunken shield still deflects and channels much of the incoming solar energy, but it does so closer to the planet, exposing satellites and upper atmospheric regions that are usually more sheltered. The 78 percent figure is a measure of that compression, not a literal loss of the magnetic field. By comparing the satellite data and modeling results with the more sensational online narratives, I see a gap between the real, quantifiable risks and the way they are sometimes dramatized, a gap that can either spur overdue investment in resilience or, if left uncorrected, feed fatalism and misinformation.

Why this storm is a warning shot for the satellite economy

Even without a total collapse of the magnetosphere, the recent superstorm delivered a clear warning to the satellite industry. Constellations in low Earth orbit, such as SpaceX’s Starlink or OneWeb, already have to contend with atmospheric drag and radiation, but they usually operate well inside the magnetosphere’s protection. When the plasma shield shrinks, those satellites face a double challenge: increased drag from a heated upper atmosphere and a more hostile radiation environment that can degrade electronics and solar panels. The event that compressed Earth’s shield by nearly 80 percent effectively stress-tested the assumptions behind the rapid expansion of commercial space infrastructure, a point underscored in analyses of how a solar storm can threaten satellites when the magnetosphere is squeezed.

For operators of navigation, communications, and Earth observation satellites in higher orbits, the implications are even more direct. Many of these spacecraft were designed based on historical records of geomagnetic storms that did not include such extreme compression of the magnetosphere, which means their shielding, redundancy, and fault management systems may not fully account for the conditions seen in this event. As I look at the trajectory of the satellite economy, with thousands of new platforms planned for launch in the coming years, the lesson is clear: space weather resilience can no longer be treated as a niche concern. It has to be built into hardware design, constellation architecture, and operational playbooks from the start, or the next superstorm could turn a profitable orbital network into a liability overnight.

Preparing for the next superstorm in a crowded sky

The recent compression of Earth’s plasma shield did not trigger the kind of global blackout or navigation collapse that worst-case scenarios envision, but it came close enough to expose the seams in current preparedness. Space weather forecasting has improved, yet the lead times and confidence levels are still limited, especially for the most extreme events. To protect GPS, power grids, and other critical systems, operators need not just alerts that a storm is coming but actionable guidance on how severe the magnetospheric compression is likely to be, which orbits will be most exposed, and how long the elevated risk will last, insights that depend on the kind of multi-satellite observations and modeling showcased in the reconstruction of this storm.

As I weigh the evidence, the path forward looks less like a single technological fix and more like a layered strategy. That means hardening satellites and ground infrastructure against radiation and induced currents, building redundancy into navigation and timing systems so that GPS is not a single point of failure, and integrating space weather scenarios into everything from grid planning to aviation routing. It also means improving public communication so that when the next superstorm hits, people understand both the seriousness of a 78 percent shrinkage of Earth’s plasma shield and the practical steps being taken to manage the risk. The recent event was a vivid reminder that our digital civilization is built inside a magnetic cocoon that can flex and falter, and that planning for those moments is no longer optional.

More from MorningOverview